Racism in Medicine’s Inauspicious Moments – A Brief Timeline

The COVID-19 pandemic further revealed health care and socioeconomic disparities in American society. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, if you’re Black or Latino in the U.S., for instance, you are almost twice as likely to die from COVID-19 as white or Asian-Americans. Multiple sources, including the New England Journal of Medicine, say early indications of African-American COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy were based on a long history of poor medical treatment of Black, indigenous and other people of color. Here is a look at some historical events involving the Black population.

1840s

Credit: Library of Congress

Dr. J. Marion Sims, described as “the father of modern gynecology,” “leases” three enslaved women in Alabama on whom he performs crude experiments without anesthesia. He later serves as president of the American Medical Association and American Gynecological Society. In 2018, the women – Anarcha, Lucy and Betsy – are recognized in the book, Medical Bondage, for their contributions and sacrifices in advancing gynecological care. A statue to them is erected in Montgomery, Ala.

1860s

Credit: Library of Congress

Spirometers used to measure lung capacity of Union soldiers during the Civil War incorrectly determined Black soldiers had inferior bodies, as white soldiers had higher lung capacity. This was used to establish a “race correction” factor. Those “race specific equations” were revised in the 1970s and later applied when assessing lung function of other racial and ethnic groups. Today, both the American Thoracic Society and American College of Chest Physicians are addressing elimination or rethinking of these factors and equations in interpreting lung function tests.

1918-20

Credit: American Journal of Nursing

During the Spanish flu pandemic, Black people were turned away from white hospitals for care. They had to go to Freedmen's Hospitals or U.S. Public Health Service clinics in schools. Black patients, more likely to die from the flu, relied on Black doctors, nurses and lay people to take care of the sick.

1930s

Credit: National Archives

U.S. Public Health Service syphilis study at Tuskegee Institute enrolls 600 poor Black men for “Free Blood Test; Free Treatment.” None of the 399 with syphilis were treated; they were just observed until they died. The study finally became public and was halted in 1972. Their story was cited in 2021 as a reason for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Blacks.

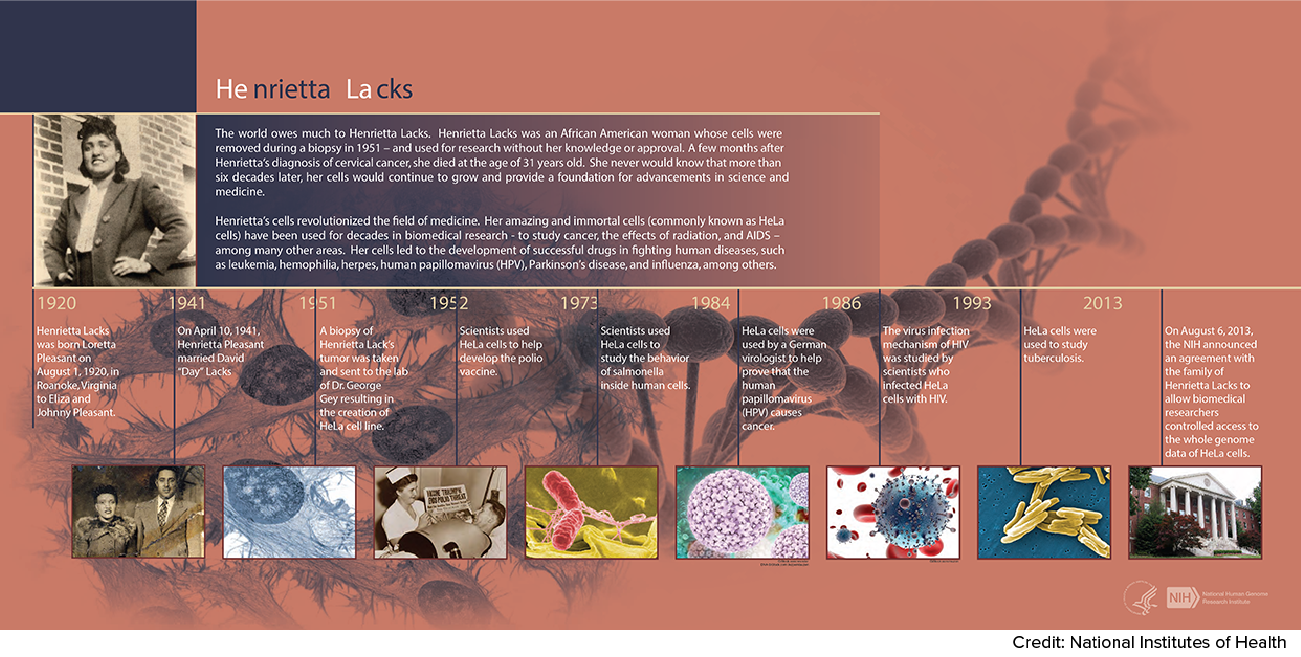

1950s

Henrietta Lacks, a 30-year-old woman in Baltimore, is diagnosed at Johns Hopkins Hospital with cervical cancer, and samples of her cells are taken without her knowledge or consent. Those cells, among the first to be grown outside of the body, live on today and have been the source of a plethora of medical breakthroughs, including the polio and HPV vaccines, cancer treatment and in vitro fertilization. Her family filed a lawsuit in 2021 against a biotechnology company they claim profited from the “stolen” cells.

1970s

Nephrologists begin establishing equations for kidney function now known as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in studies that were limited by lack of racial and gender diversity. Among uses for these calculations are scoring who gets a kidney transplant first. Adjustment factors included age, sex, body weight and whether they’re African American. By 1999, race was among 16 factors included and “validated.”

2020s

After extensive review and outreach (including testimony by UArizona College of Medicine – Phoenix medical students), the American Society of Nephrology and National Kidney Foundation issued a joint statement in 2021 that they were removing race from eGFR calculations.