Improving Health and Wellness Begins with Basic Science

A key contingent at the University of Arizona Health Sciences, basic scientists are undaunted by setbacks, a critical trait for making discoveries.

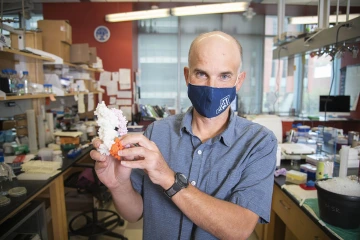

Dr. Michael D.L. Johnson investigates how copper interacts with bacteria. His research might someday help solve problems relating to antibiotic resistance.

When the Kuhns Lab created its first successful batch of T cells studded with five specially engineered antigen receptors and co-receptors, the room was bursting at the seams with eager anticipation.

“There were four of us in the lab late at night, huddled around the flow cytometer, watching as the data came across the computer screen. We were waiting with bated breath to see what the results might be,” recalled Michael Kuhns, PhD, associate professor of immunobiology at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson. “To invent something that’s never existed before, to taste discovery – that is really rewarding.”

Dr. Michael Kuhns demonstrates how engineered immune cell receptors might fit together into a more complex molecular machine.

Dr. Kuhns calls himself an “unabashed basic scientist,” a researcher who investigates the fundamental biological mysteries of how cells and molecules interact in the body. If those discoveries someday lead to treatments for debilitating diseases, that’s the proverbial icing on the cake. But for nonscientists, it can be difficult to link the process of initial basic scientific discovery with the improvements in health and wellness that society reaps down the line.

Dr. Kuhns says basic scientists are motivated by pure curiosity.

“I’ve got an engineer’s mindset. I like to take things apart and figure out how they work. We look at these molecular machines and ask how these parts fit together,” he said. “We can use evolution’s blueprint for these molecular machines to build new molecular machines that may have a therapeutic function.”

A nonlinear process

Most people might assume science is conducted like a lot of jobs, with clear objectives and timelines. But scientists operate a little differently, continually refining their experiments to get more reliable or detailed results, using what they call an iterative process.

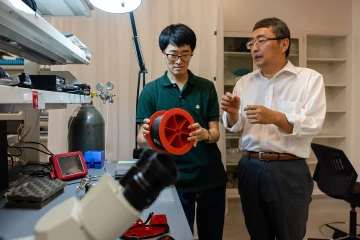

Shenfeng Qiu, PhD, MD, MPH, associate professor of basic medical sciences at the UArizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, says the scientific process isn’t linear.

Dr. Shenfeng Qiu (right) works with postdoctoral fellow Dr. Hee-Dae Kim of Dr. Deveroux Ferguson’s lab. The two researchers’ labs collaborate to tackle big questions in neuroscience.

In this sense, science starts out like a rough sketch on a napkin, which over time is filled in with details and colors. Eventually, the picture moves from the napkin onto an expansive mural. A nuanced view of biology slowly emerges, thanks to the work of countless scientists adding small flourishes to the portrait of life. This incremental accumulation of information might frustrate those who don’t understand why science hasn’t already found cures for diseases like cancer or Alzheimer’s disease, but it allows scientists to look at old questions with fresh eyes and get one step closer to the answers.

“That moment when you know something nobody else on the planet knows – that’s the thrill.”Michael Kuhns, PhD

Michael D.L. Johnson, PhD, assistant professor of immunobiology at the College of Medicine – Tucson, compares science’s iterative process to cleaning a house.

“You make up the bed, you vacuum the floor, you clean the windows, but you can’t call the whole job done. On its surface, it looks clean, but underneath the surface, there are all these other things we need to do,” Dr. Johnson said. “Did you use an air purifier? Did you change the filter? Have you dusted the ceiling fan lately? Wait, you have to actually clean your ceiling fans? The more we research, the more we learn what’s underneath the surface.”

Revisiting old questions with new information takes patience, especially when many people would rather move from one task to the next with constant forward motion. Basic scientists, however, know that to do science correctly, they must retrace their steps as they learn more about what lies underneath the surface.

Try, try again

Most experiments don’t prove the hypotheses being tested, but scientists see these results as opportunities for growth and learning, giving themselves space to keep plugging away when things don’t work out as they envisioned.

Dr. Qiu says failure is a part of science.

“When we were kids, we all heard of Edison, who probably failed a thousand times, maybe more, before he invented the light bulb,” Dr. Qiu said. “Failure is a bad thing if you don’t learn anything from it. We need to learn from failure to advance in science, to refine our knowledge, and move on to achieve better things.”

Dr. May Khanna says students need to experience failure to build resilience, empowering them to make future discoveries.

As long as an experiment is designed to generate accurate data and account for variables, the results are what matter, regardless of whether they confirm a hypothesis.

“If you disprove your hypothesis, it’s not a failed experiment. If you test your hypothesis, and you are correct or incorrect, I would call that a successful experiment,” Dr. Johnson said. “Being incorrect is not the same as failing. If you learn something, that’s not a failure. Failure is in experimental design. If you don’t design it correctly, that’s a failed experiment.”

May Khanna, PhD, associate professor of pharmacology at the College of Medicine – Tucson and a member of the BIO5 Institute, incorporates the expectation of failure into her approach to teaching. She says normal classrooms, by grading students on the A-to-F scale, don’t reflect real life, which is full of failures that make people stronger. She emphasizes this message to everyone working in her lab.

“The very first thing that comes out of my mouth is, ‘You have to be willing to fail, because you will not succeed until you fail.’ Then they fail, and they fail, and they fail, and boom, they succeed,” Dr. Khanna said. “Some of my best researchers have been kids who have struggled, who have had such a tough time in life, and then realize, ‘Wait, I’m used to this.’ Welcome to research!”

Lasting results can take a long time

Science is incremental and nonlinear by design, but the general public can be frustrated by its pace, which they might perceive as too slow.

“People expect to have a cure overnight. Like, ‘Why haven’t you cured cancer yet?’ But you can’t just speak it into existence like that,” said Dr. Johnson, who is also a member of BIO5. “It’s not a singular task to make a cure. There are all these different components that go into it.”

Dr. Kuhns hopes his lab’s highly customized T cells may someday lead to a therapy that can eliminate rogue immune cells that cause Type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases, which affect more than 24 million Americans, and also be used to fight some types of cancer. The possibilities are wide open, and the daily opportunity to make fundamental discoveries that set the stage for tomorrow’s innovations gets him out of bed every morning.

“Basic science is challenging and stressful, but it’s rewarding. We had a result in the lab the other day, and I was telling the people who did the experiment, there are 8 billion people on this planet, and you two are the only ones in the world who know that answer,” he said. “For those of us who go into this business, that’s the thrill: that moment when you know something that nobody else on the planet knows.”