Valley Fever Center for Excellence Celebrates 25 Years

The center focuses on research, outreach and education to fulfill its mission of protecting people against a deadly fungal disease native to the Southwest.

Valley fever is much better understood worldwide thanks to the UArizona Valley Fever Center for Excellence’s research, education and outreach efforts.

Twenty-five years ago, valley fever was an obscure fungal disease from the southwestern U.S. few people understood. But John N. Galgiani, MD, knew the severe health consequences of this largely respiratory infection and took that knowledge to the Arizona Board of Regents, which authorized the creation of the University of Arizona Valley Fever Center for Excellence.

Today, valley fever is much better understood worldwide – and a vaccine to prevent the disease is much closer to becoming reality – due to the UArizona Valley Fever Center for Excellence’s research, education and outreach efforts.

Valley fever: a devastating disease

Valley fever, also known as coccidioidomycosis or cocci, is caused by inhaling spores of Coccidioides, a fungus found in the soil of dry areas of the southwestern U.S. It affects people and animals, particularly dogs. For most people, infections are minor. For some, symptoms mimic a long-lasting case of the flu or pneumonia. For others, severe reactions include lung abscesses or nodules, and infections that spread to the joints, bones or brain.

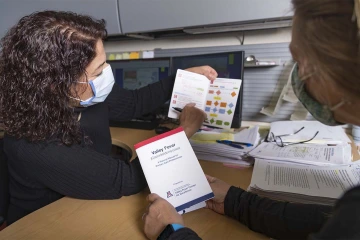

Outreach is one of the missions of the Valley Fever Center for Excellence. Here, Fariba Donovan, MD, PhD, educates a standardized patient about the fungal disease.

Because of its similarity to the flu and pneumonia, and more recently COVID-19, valley fever often is misdiagnosed. More severe manifestations even have been confused with cancer. Patients who are not accurately diagnosed might go for weeks or months being treated ineffectively with antibiotics instead of antifungals.

The more severe cases of valley fever can result in surgeries, extended rehabilitation and lifelong treatment – as well as premature death. Up to 200 people per year die of valley fever, which infected 18,399 people in 2019, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Testing and prevention research

Research efforts at the Valley Fever Center are focused on increasing knowledge of how and why valley fever affects people differently, creating more effective rapid diagnostic tools, and developing a live, yet safe, vaccine with the goal of preventing the fungal disease.

Dr. Galgiani, a professor of infectious diseases at the College of Medicine – Tucson and a BIO5 Institute member, is leading several National Institutes of Health-funded studies, including one to identify why some people barely get sick and others die of valley fever.

John N. Galgiani, MD, (center) founded the Valley Fever Center for Excellence in 1996.

Another center researcher, Fariba Donovan, MD, PhD, an infectious diseases assistant professor, is working to assess biologic response modifiers, or biologics, that are used to treat a number of conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn’s disease but may leave some users at greater risk of valley fever. For now, she’s focused her studies on arthritis in partnership with UArizona Arthritis Center Director and Rheumatology Division Chief C. Kent Kwoh, MD.

Dr. Galgiani also is collaborating with Michael D.L. Johnson, PhD, assistant professor of immunobiology, on a diagnostic test with a 20-minute report time. The test will provide greater sensitivity to more accurately detect valley fever earlier in the infection than any tests currently available.

According to Dr. Galgiani, a patent for the rapid test already has been applied through Tech Launch Arizona, the arm of the university that helps commercialize technology resulting from research.

Tech Launch Arizona also assisted with the licensing of a valley fever vaccine to Anivive Life Sciences. While the vaccine is for dogs, it is a promising step toward a human vaccine. Anivive expects to be ready to test the vaccine in dogs later this year.

Lisa Shubitz, DVM, is part of the research team that aims to develop a canine vaccine for valley fever. Donations from Arizona dog owners fueled the early research for a canine vaccine, which is a promising step toward a vaccine for humans.

Dr. Galgiani noted the canine vaccine wouldn’t be possible without breakthroughs several years ago by Lisa Shubitz, DVM, a Valley Fever Center researcher and veterinarian who specializes in mouse models, and Marc Orbach, PhD, a plant sciences professor with the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Dr. Orbach discovered that Coccidioides and Cochliobolus, a corn fungus, share a common gene, Delta CPS1. Removing Delta CPS1 from the corn fungus made it less harmful, and doing the same to Coccidioides made it completely harmless in rodent models.

Dr. Orbach is now studying the genetics of Coccidioides to determine why deleting one gene defanged the fungus’s ability to infect. Knowing that will be crucial to developing a human vaccine, Dr. Galgiani said.

Education and outreach efforts

Dr. Galgiani said the total cost of getting the dog vaccine created and approved will be about $12 million. Developing a human valley fever vaccine is more on the order of $150-200 million. Grants are likely needed to cover much of that cost, particularly in the early stages, and the center’s outreach and education efforts are building increasingly strong community support in Arizona to enable that to happen.

Donations from dog owners in Arizona and a related grant from a California Rotary Club enabled the Valley Fever Center to complete mouse model testing that led to a $4.8 million National Institutes of Health grant to pursue the dog vaccine.

According to Dr. Galgiani, the cost of creating and getting the dog vaccine approved will be about $12 million. Developing a human valley fever vaccine will cost closer to $150-$200 million.

“The Arizona dog community, these people are just amazing. They really are. This is the vaccine that dog owners made,” Dr. Shubitz said.

For Dr. Galgiani, who also serves as medical director for the Banner – University Medicine Valley Fever Program in Tucson and Phoenix, education includes developing clinical guidelines for clinicians on how to recognize the disease, test for it and treat it. He has presented to groups in Mexico, Europe and Asia, so they can better diagnose valley fever among business travelers and tourists returning home after trips to the Southwest.

Education also includes hosting events such as the Coccidioidomycosis Study Group 65th Annual Meeting held online April 16-17. It brought together about 150 researchers for a virtual look at the state of research into valley fever.

Dr. Galgiani welcomes other collaborators with an interest in valley fever research.

“There’s room for everyone. This is not an overpopulated field, and there’s probably something to learn because of that,” he said. “There are lots of questions yet to be answered.”