Pediatric Care Survey Shines Light on Coronavirus’s Darkness

Health Sciences researchers spearhead global effort to capture a snapshot of real-time critical care of pediatric COVID-19 patients.

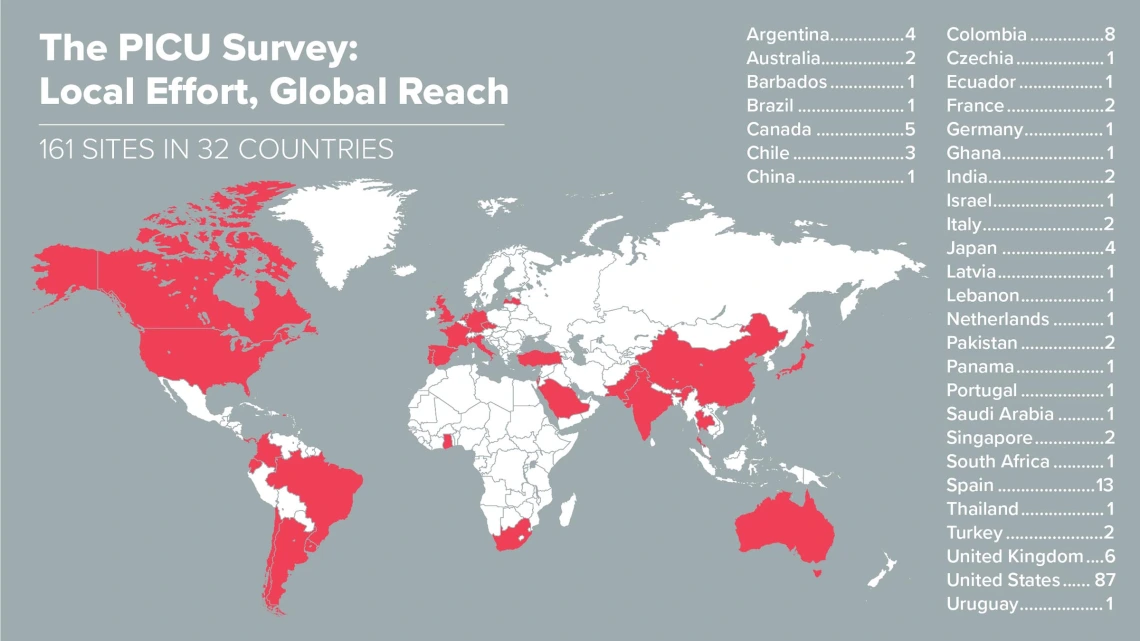

With Health Sciences coordinating the effort, 161 sites across six continents gathered data about how pediatric critical care units were responding to the COVID-19 crisis.

Imagine working in a pediatric intensive care unit, a section of the hospital that provides critical care for acutely ill and severely injured children. You already need to take extraordinary measures to keep your vulnerable patients safe. And then a dangerous new virus rears its ugly head, bringing with it an abundance of unknowns and a paucity of evidence.

Katri Typpo, MD, oversees a patient in the pediatric intensive care unit in this archival photo from 2013.

“There were a lot of online chat groups and social media platforms where people in the ICU communities were asking questions — because we had no information about how to care for these kids,” Dr. Typpo explained. “Each question might have 10 different responses, and you couldn’t be certain the person answering the question was an ICU doc! I found it very difficult to gather information to understand what other sites were doing to care for kids with COVID-19 — or even if COVID-19 was causing critical illness in children.”

“Everyone pulled together to help each other do the best job they can taking care of kids.”Katri Typpo, MD, division chief of Pediatric Critical Care, University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson

In that low-information environment, Dr. Typpo and her colleagues tapped into their established research networks to learn whether pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) across the world had these patients, how they were testing them, and how they were treating children with COVID-19 and providing protective equipment for workers. In the absence of peer-reviewed scientific literature, Dr. Typpo planned to use a survey of other PICUs to obtain a snapshot of what her colleagues were doing around the world.

“At the very least, we can learn what the emerging standard of care is across the world,” Dr. Typpo said. “Not that we would suddenly change how we’re treating children in Tucson in response to a survey, but it would affirm our choices — or have us question them and reexamine the evidence. It’s one piece of the puzzle to use to make a decision about how to care for patients. The most important piece is the scientific, peer-reviewed literature.”

Painting a picture

The project launched the week of March 20. The survey was sent weekly, first to all sites in Dr. Typpo’s research network, and then to more and more sites as word of the survey spread within the pediatric critical care community. By the sixth week, 161 sites in 32 countries across six continents were participating.

“With rapid information coming out about this pandemic, we decided to send a survey every single week to see if decision making was changing over time, because the standard of care was a moving target,” Dr. Typpo said. “We had really great response. People were feeling this void, that there was this lack of information.”

With so little information about COVID-19 in pediatric patients, the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson coordinated an international effort to “crowdsource” information from peers until higher-quality evidence was published.

Every week, participants would answer questions to paint a picture of how they were handling this crisis in their own units. One recurring question concerned which medications were best for treating COVID-19.

“We started out with a list of medications that were published in the literature in adults. There was no information whatsoever about whether these treatments were successful or being used in children,” Dr. Typpo said. “There were some shifts over the course of the survey in terms of what medications sites were using, I think in response to reports coming out in the scientific literature and guidelines that were published about when someone should use treatments.”

Overall, Dr. Typpo says the biggest lesson learned from this survey was that access to this type of data in a low-information environment can help physicians be confident they are on the right path — and know when they might want to look more deeply into the medical literature to inform their decision making. They were able to share information from units that were already seeing COVID-19 patients with units that did not yet have these patients. She gave the example of PPE, or personal protective equipment.

“We specifically asked about PPE, and it was quite comforting for our nurses to know the PPE we were using and the choices we were making about how to use PPE aligned well with what other sites were doing,” Dr. Typpo said. “We found the results weren’t necessarily changing what we individually decided to do in the PICU, but it made us feel comfortable that what we’re doing here is what everybody else in the world is doing to care for these patients.”

Next steps

Katri Typpo, MD

“It was a way the University of Arizona Pediatric Critical Care Division could do something beneficial during this pandemic,” Dr. Typpo said. “The most rewarding part was being able to connect with pediatric ICUs across the globe. Everyone pulled together, and it was clear that everybody wants to help each other do the best job they can taking care of kids.”

The team will distribute two follow-up surveys over the next two months to assess how the growing medical literature is changing the way patients are treated in hospitals. A third follow-up in the fall is possible, especially if a “second wave” of COVID-19 materializes.