Using data to make better medical decisions

The Data Science Fellowship equips health care researchers and professionals to leverage data to improve medical knowledge and care.

Ajay Perumbeti, MD, is a pediatric hematologist oncologist who is pairing his vast clinical expertise with a growing base of expertise as a data scientist with the intent of gaining new knowledge that will benefit patients.

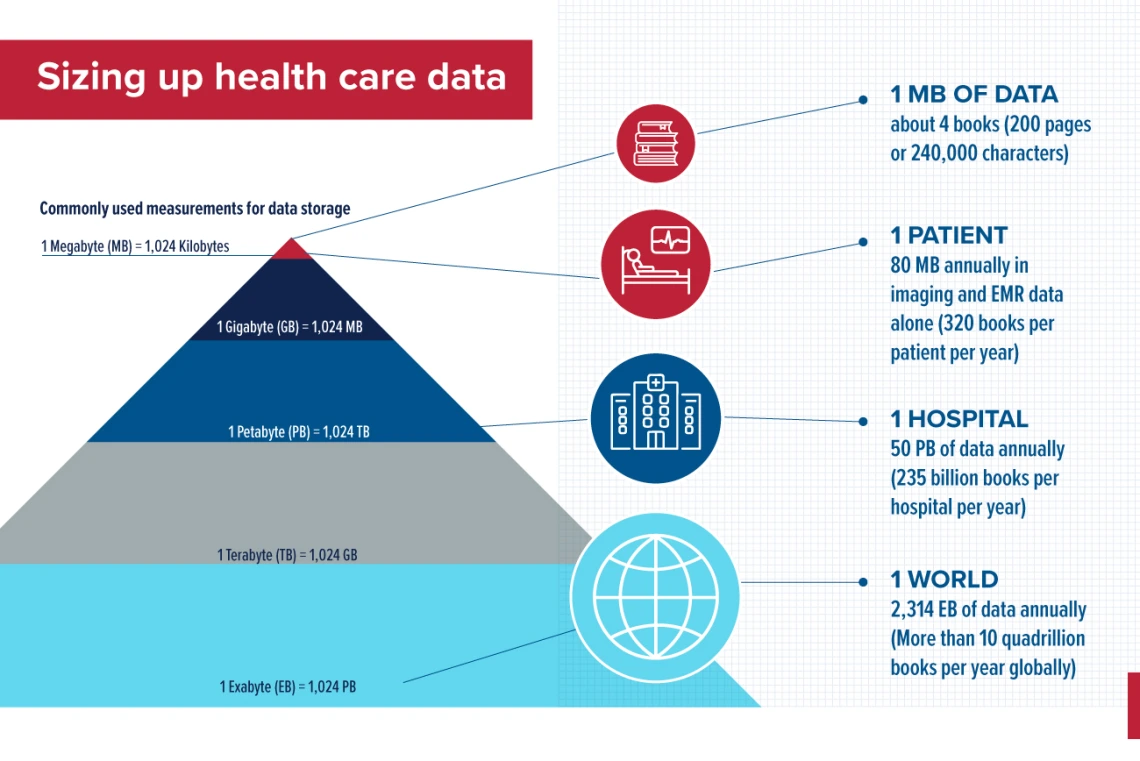

Long before the COVID-19 pandemic, when billions of vaccine doses were administered globally, the health care industry was generating enormous amounts of data. That volume of data is only increasing, with RBC Capital Markets reporting that 30% of data worldwide is generated by the health care industry. That growth outpaces other industries, including manufacturing, financial services and entertainment.

Ajay Perumbeti, MD, has more than 20 years of experience in pediatric hematology oncology. He completed his fellowship training at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Hoxworth Blood Center.

At the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society 2023 Global Conference, population health vendor Arcadia reported that a single hospital can generate as much as 50 petabytes of data each year. One petabyte is the equivalent of 500 billion pages of standard printed text.

That all raises important questions: are copious amounts of data too much of a good thing? How can the data be used to improve patient care? Who analyzes the data and uses it to improve the health care system?

This is where two very distinct disciplines – doctors and data scientists – intersect. A doctor is trained in medicine and patient care but lacks the skills a data scientist possesses. A data scientist is adept at collecting, analyzing and interpreting data to drive informed decision making, but does not have the medical acumen and skills required to treat patients.

Bridging the gap between these professions can maximize the benefits of the enormous amounts of health care data that are now available. Ajay Perumbeti, MD, a clinical informatics fellow at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, sees value and potential in using data to improve patient care. Trained as a pediatric hematologist oncologist, Dr. Perumbeti has since shifted his career focus to analyzing and building tools for clinical and bioinformatic data sets.

“I was struck by the amount of data being collected,” Dr. Perumbeti said. “And I had some intuition that maybe it would be useful to take this data to help us make good medical decisions. I think that computational approaches are complementary to a physician’s experiences. How we put those together is critical for improving health care.”

To advance his knowledge of how to better use data, Dr. Perumbeti recently completed the Data Science Fellows program, part of a UArizona Health Sciences strategic initiative to increase the use of data science and analytics in health care.

Through the program, fellows develop and exchange the data science expertise needed to answer challenging research questions in health sciences. Data Science Fellows also receive intensive training and mentoring focused on the use of open science, which focuses on the reproducibility of data, and computational infrastructure, which provides the ability to automate processes to efficiently ease human labor in data science research.

Carlos Lizárraga, PhD, MSc, a computation and data science educator at the Data Science Institute in the UArizona Office of Research, Innovation and Impact, explained that data scientists search for information that can be extracted from datasets to analyze relationships between variables and identify general behavior or specific patterns. The types of datasets can be quite broad, and in health sciences may include text and numeric datasets of DNA sequences, sentences or vital signs, for example, and imaging datasets of X-rays or scans. Computational tools such as algorithms are then used to create forecasting models. Ultimately, clinicians can use this information to identify the probability a person will develop a certain disease.

A bandwidth problem

Dr. Perumbeti received a Doctor of Medicine degree from Northeast Ohio Medical University in 2001. In the years since, he has accumulated a wealth of knowledge based on his own interactions with individual patients under his care.

Dr. Perumbeti hopes to use data science to incorporate a population health perspective when treating conditions such as sickle cell disease, which occurs when red blood cells contain an abnormal form of hemoglobin that causes them to become sickle-shaped rather than round.

Computational approaches to medicine can help eliminate or correct bias based on experiential knowledge. Dr. Perumbeti, who is board certified in pediatrics, pediatric hematology oncology and transfusion medicine, began to think about his patients in a broader context.

“I had a lot of patients with sickle cell disease. I could get a sense of how they were doing individually, but I did not have a good sense of how they were doing as a whole,” Dr. Perumbeti said. “I wasn’t able to compare them to patients in other clinics or across the country or from year to year. I started thinking about how we could look at patients with a particular condition from a population health perspective.”

Along with his clinical responsibilities, Dr. Perumbeti was working in a basic science lab studying gene therapy for sickle cell disease, which is a group of inherited red blood cell disorders. Sickle cell disease is the most common inherited blood disorder in the United States, affecting an estimated 100,000 people, according to the American Society of Hematology.

“Bad information is just as bad as no information.”

Ajay Perumbeti, MD

Investigating sickle cell disease in the lab was Dr. Perumbeti’s first foray into bioinformatics, the science of collecting and analyzing complex biological data such as genetic codes. He believes this knowledge base combined with his experience as a clinician can help improve decision-making.

“With advances in science, the complexity of medicine was dramatically increased, and humans started having a bandwidth problem,” Dr. Perumbeti said. “As a clinician, I can only retain so much knowledge and information. I can only share so much with others. It is difficult to learn and keep up with the information that is required in order to make the best decisions.”

Data-driven decisions

Understanding how to leverage data to improve efficiency of decision making is an emerging challenge for health care leaders. Dr. Perumbeti and his colleagues are among those who already see the advantage of leveraging data science tools and methods to continue the advancement of science.

Dr. Perumbeti’s research uses machine learning and artificial intelligence to predict iron deficiency in women, children and blood donors. Some of this work will be presented at the BioIron meeting this year in Australia. He is also working on bioinformatics approaches to better understand iron transfer from mother to child.

“Reproducible and sharable code is essential to build durable tools and leverage team science for computational solutions to the complex problems in medicine,” said Dr. Perumbeti, who later this year will present some of his work at the BioIron Conference, a premier iron biology conference in Darwin, Australia.

“Bad information is just as bad as no information,” Dr. Perumbeti said. “Good science that is reproducible from a computational medicine perspective is critical to get where we need to go.”

Dr. Perumbeti says he is just scratching the surface of becoming a master in data science, but he credits the Data Science Fellowship with advancing the skills that will allow him to build and share knowledge that will be helpful to his patients.

“The Data Science Fellowship was an amazing opportunity for me,” Dr. Perumbeti said. “It provides the foundational and technological knowledge necessary to help you figure out how to apply these skills in an appropriate way that will one day help people. If we use the data the right way, we can make better decisions.”

Our Experts

Ajay Perumbeti, MD

Clinical Informatics Fellow, College of Medicine – Phoenix

Nirav Merchant, MS

Director, Cyber Innovation

Director, Data Science Institute

Interim Director, Center for Biomedical Informatics and Biostatistics

Member, BIO5 Institute

Carlos Lizárraga, PhD, MSc

Computation and Data Science Educator, Data Science Institute

Contact

Blair Willis

UArizona Health Sciences

520-419-2979

bmw23@arizona.edu