Bad Bugs: The Vaginal Microbiome and Cancer

Melissa Herbst-Kralovetz of the UArizona College of Medicine – Phoenix links an off-kilter vaginal microbiome to increased gynecological cancer risk.

Microbes get a bad rap, but only a fraction of them cause disease, while some are integral to human health, coalescing to form the microbiome — the community of microbes that take up residence in the body. The human microbiome is receiving a flood of attention for its potential role in every aspect of health.

Melissa Herbst-Kralovetz, PhD, leads a team of researchers working to identify the connection between bacteria that live in the vagina and gynecologic cancer risk. (Photo: Tabbitha Mosier, UArizona College of Medicine – Phoenix)

Melissa M. Herbst-Kralovetz, PhD, associate professor at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, leads the Women’s Health Microbiome Initiative, an ambitious undertaking that brings cancer biologists, immunologists and physicians together in collaboration. Together, they work to uncover connections between vaginal microbiota — the microscopic organisms that reside in the lower reproductive tract — and women’s health, investigating how vaginal microbes interact with the rest of the body to promote or harm health.

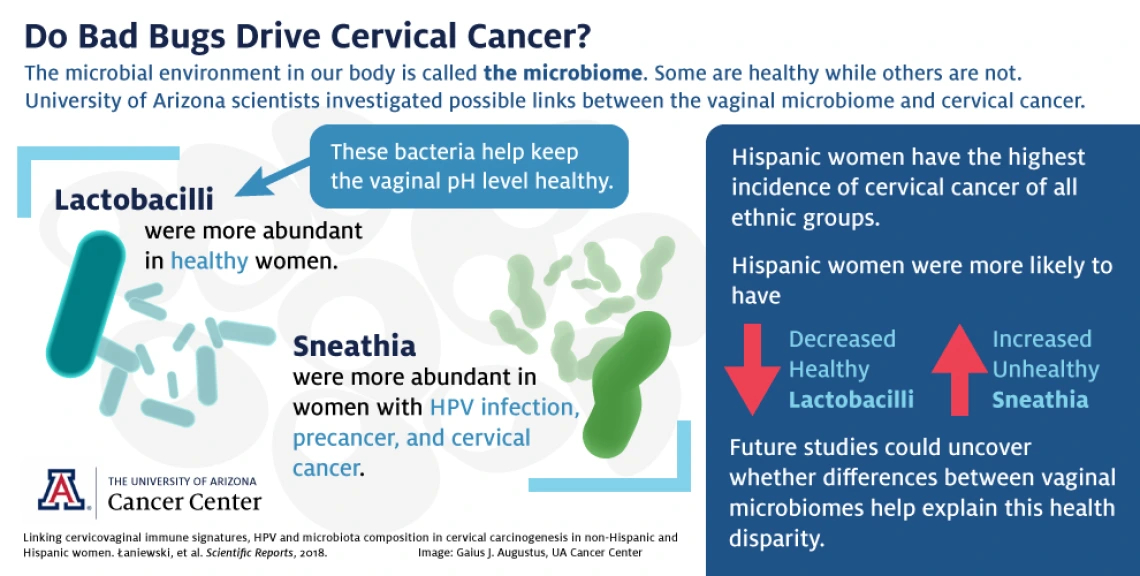

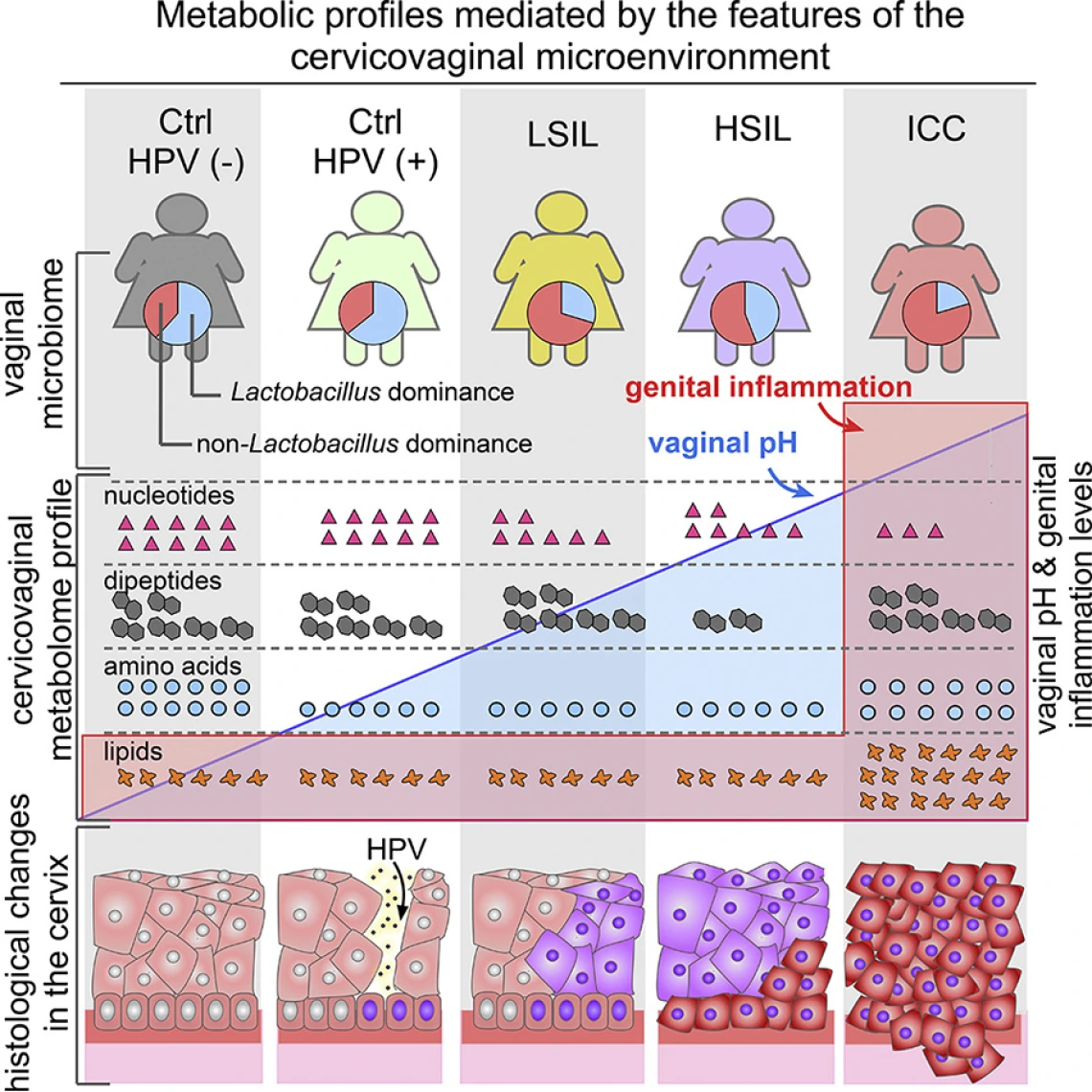

Some species of bacteria promote a healthy vaginal environment. For example, lactobacilli play a major role in regulating vaginal pH, creating an acidic environment hostile to microbes responsible for diseases like trichomoniasis and bacterial vaginosis. And women with lactobacilli-dominant vaginal microbiomes are more likely to prevent or clear human papillomavirus infections. However, when the vaginal ecosystem is thrown off balance — a condition called dysbiosis — the vagina may be more susceptible to disease.

Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz’s lab focuses on the way a dysbiotic vaginal microbiome could promote inflammation, which is a factor in the development of cancer. Although inflammation is a normal part of the immune response, in which the body fights against injuries or infections, chronic inflammation can damage tissue and DNA, setting the stage for tumor formation.

Which came first: Bad bugs or cancer?

The bacterial communities thriving in the vagina could be laying the groundwork for health — or for cancer and other diseases. Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz’s lab is hard at work teasing out the possible connections between the microbiome and two types of gynecologic cancer: endometrial cancer and cervical cancer.

Endometrial cancer, which strikes the lining of the uterus, is projected to cause more than 12,000 deaths in 2019. The causes of endometrial cancer aren’t known, but Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz is investigating the possibility of “bad bugs” traveling from the vagina into the uterus to cause damaging inflammation, in turn triggering cancer.

“We are really at the ground floor with this research,” she says. Her lab could be the first to clarify the association between the vaginal microbiome and endometrial cancer risk, particularly when it comes to questions about causation. For example, patients being treated for endometrial cancer are less likely to have thriving communities of vaginal lactobacilli. Is the imbalance in their vaginal microbiomes a cause of cancer — or is it an effect of cancer?

“Causation is always tricky to establish in microbiome studies,” says Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz. “We are at an early stage, but if we know what bacteria might be acting as ‘drivers’ or ‘passengers’ in carcinogenesis, we can study those individually or as communities to understand how they are functioning to alter the local microenvironment.”

Endometrial cells colonized with “good” bacteria called Lactobacillus crispatus (colored purple). Image courtesy of the Herbst-Kralovetz Lab

To answer that question, a Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz and her team studied 100 premenopausal women to find links between vaginal bacteria and cervical cancer. Her team found that women without cervical abnormalities are hosts to different communities of vaginal bacteria than women with cervical cancer and precancer, a discrepancy that reveals a relationship between “good” bacteria and cervical health, and “bad” bacteria and increased cancer risk.

“In cancer and precancer patients, lactobacilli — good bacteria — are replaced by a mixture of bad bacteria,” says Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz. The women with the most severe cervical abnormalities were more likely to have the lowest lactobacilli populations — and on the flip side, flourishing lactobacilli communities tended to be found in women without cervical precancer or cancer. Likewise, “bad” bacteria, called Sneathia, were linked to HPV infection, precancer and cervical cancer.

The bacterial communities thriving in the vagina could be laying the groundwork for health — or for cancer and other diseases.

Sneathia are rod-shaped bacteria that have been associated with other gynecological conditions, including bacterial vaginosis, miscarriage, preterm labor, HPV infection and cervical precancer. Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz’s team is the first to find that a substantial Sneathia population is associated with all stages of the HPV-to-cancer continuum, from initial HPV infection to precancer to invasive cervical cancer.

What’s unknown is whether Sneathia species actively promote HPV infection or cancer formation, or if HPV or cancer creates an environment that’s more hospitable to Sneathia and less friendly to lactobacilli. The current study offers only a snapshot of women at one point in time — it doesn’t establish a cause-and-effect relationship.

“There’s really not a lot in the literature about how Sneathia functions in the reproductive tract,” says Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz. “How Sneathia may be impacting the hallmarks of cancer is an active area of investigation in our lab.”

Melissa Herbst-Kralovetz, PhD, is looking for connections between the vaginal microbiome and cancer. (Photo: Tabbitha Mosier, UArizona College of Medicine – Phoenix)

Fighting health disparities

Roughly half of the patients studied were Hispanic, while the other half were of non-Hispanic origin. Hispanic women have the highest incidence of cervical cancer of all racial and ethnic groups. Studies assessing factors such as race and ethnicity in cancer risk are important for understanding why some populations are disproportionately affected by cancer.

“I wanted to truly reflect the Arizona population in our study,” says Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz. “Latinas are at a higher risk of cervical cancer. A long-term goal of mine is to help address that health disparity.”

The team found that Hispanic women were more likely to have decreased Lactobacillus populations and increased Sneathia populations. Perhaps differences in the vaginal microbiome is one factor behind Hispanic women’s increased risk for cervical cancer. Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz adds that her team recently received funding to expand their study to include Native American women.

Promoting an acidic environment

Yogurt is a familiar source of probiotics, but its gynecological health benefits are dubious. Image licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license

“High pH is a great reflection of the vaginal microbiome composition,” says Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz. “Lactobacilli produce lactic acid that directly lowers the pH. If you have high levels of lactobacilli you’re going to have a lower vaginal pH, and that’s associated with health.”

Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz’s team found that, as the vaginal environment loses acidity, cervical abnormalities become more severe. The team is the first to show a relationship between elevated pH and advanced cervical abnormalities.

Though we might be tempted to identify the bacteria associated with increased vaginal pH and wipe them out with antibiotics, the truth is these drugs aren’t very precise weapons, and they take a lot of friendly bacteria with them. Instead of trying to eliminate bad bugs, what if we could nurture the good bacteria that are associated with health? Many consumers hope to ward off disease with store-bought “probiotics,” or good bacteria.

Yogurt, for example, is often touted as a home remedy for yeast infections and other gynecological conditions.

“In your yogurt, you have the gut lactobacilli,” says Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz. “The vaginal lactobacilli species are very different than what you would find in your gut — or in yogurt.”

Unfortunately, we don’t yet know if it’s possible to introduce good bacteria into the vagina to promote health, and in any case, yogurt — which travels through the gastrointestinal tract, not through the vagina — probably wouldn’t do the trick. But the question has piqued the interest of researchers across the world, and it’s an area of open inquiry — perhaps in the future we’ll be able to build healthy vaginal microbiomes with intravaginal suppositories or creams. So far, however, the science hasn’t caught up to the marketing hype surrounding probiotics.

Dusting for ‘fingerprints’

Knowing more about the relationship between the vaginal microbiome and cancer development could lead to methods to detect cancer in its earliest stages. Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz is developing ways to harness knowledge about the microbiome-cancer connection and turn it into better ways to prevent, diagnose and treat cervical cancer.

Communities of bad bacteria, in addition to triggering inflammation and increasing vaginal pH, produce biochemicals that act as “fingerprints” — telltale signs of cervical precancer or cancer. These fingerprints change as disease progresses, potentially giving future doctors more precise tools for diagnosis. By identifying these fingerprints, Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz and her team have found a way to develop a better understanding of how HPV infection progresses to cancer.

“Metabolic fingerprinting has the potential to be used for the development of future diagnostics, preventatives or treatments for cervical cancer,” says Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz. “Doing so could aid in reducing mortality of the fourth-leading cause of cancer in women.”

Microbes still have a bad rap, but the 21st century is witnessing a growing appreciation for the benefits bacteria can bring. As Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz’s lab discovers more about the vaginal microbiome, a clearer picture emerges of how microbes can protect health — and possibly be enlisted in the fight against cancer.

This research was supported by the Flinn Foundation Grant Nos. 1917 and 1974, partially by the National Institutes of Health NIAID Grant 1R15AI113457-01A1 and the National Institutes of Health NCI Grant P30 CA023074, the Mary Kay Foundation℠ Translational Research Grant, and through the financial support of the Banner Foundation in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Our Experts

Contact

Health Sciences

Office of Communications

520-626-7301

public@arizona.edu