WWII soldiers liberated Europe, then helped build Pharmacy

Soldiers returning home came to UArizona on the GI Bill to grow the oldest of the Health Sciences colleges.

American troops wade ashore on Omaha Beach during the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944. D-Day, one of history’s toughest, most important battles, marked the turning point of World War II.

Photo courtesy Vernon Lewis Gallery/Stocktrek Images via Getty Images

Chuck Gin knew how to juggle.

With the help of the recent GI Bill, the World War II veteran was a student at the newly created University of Arizona College of Pharmacy. He balanced his job at a drugstore with helping his bride adjust to life in a new country. He worked shifts at his parents’ market, all while attending classes, completing homework and studying.

Tiffany Wong Grey (left) holds a photo of her late grandfather Chuck Gin, who was in the first graduating Pharmacy class. Katie Wong, holding a replica of her father’s Congressional Gold Medal awarded to Chinese American World War II veterans, said her father was proud to serve his adopted country.

Photo by Noelle Haro-Gomez, UArizona Health Sciences Office of Communications

One spring morning in 1947, though, something had to give. Gin learned that his first child was born while he was in class.

His professor sent him home from the lab, said his daughter, Katie Wong, the very one who provided the ultimate excused absence that day.

“I still don’t know how he accomplished all that he did,” she said of her father, who died in 2010 at the age of 86.

Chalk it up, perhaps, to being part of the Greatest Generation. Gin was a member of that first College of Pharmacy graduating class of 1950, most of whom had served their country and came back to attend school on the GI Bill. The college, which had just three faculty members, was decades from becoming the UArizona R. Ken Coit College of Pharmacy and didn’t even have its own building. Classes were held in surplus army tents.

Today marks 80 years since the D-Day invasion on the beaches of France, when the Allies began liberating Europe during World War II. The success of D-Day and subsequent military operations increased the urgency and development of plans to reintegrate millions of veterans into civilian society.

New beginnings

On June 22, 1944, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, better known as the GI Bill, was signed by then President Franklin D. Roosevelt to provide returning veterans with money for education, loans, unemployment payments and job-finding assistance.

“Millions of men and women came out of uniform and went back into the workforce. The bill was a way to increase their employment and boost the economy, as well as give them their due because of their service,” said John Curatola, PhD, senior historian at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans and a retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Marine Corps.

The American soldiers returned home, integrating back into society. That meant going to college for many, Curatola said. In 1947, in fact, World War II veterans accounted for nearly half of all college admissions. That was the same year the University of Arizona started its pharmacy program after a 23-year campaign led by a local pharmacist and the Arizona Pharmacy Association.

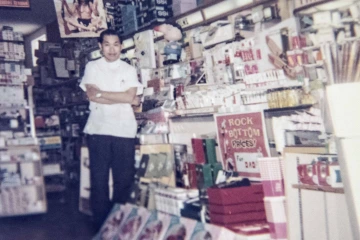

After he graduated from the UArizona College of Pharmacy in 1950, Chuck Gin opened a drug store on Tucson’s south side.

Photo courtesy of Katie Wong

In that first pharmacy class of 25 students, 92% were WWII veterans, said Metta Lou Henderson, PhD, a Coit College of Pharmacy research professor as well as an alum.

Gin’s journey to pharmacy started in Canton, China, where he was born. Gin, the oldest of four, and his parents emigrated to the United States when he was 5. He enlisted in the Army after graduating from Tucson High School, where his typing skills kept him off the battlefield, Wong said. He was proud to serve his adopted country.

“He really loved America,” she said of her father. “He felt like it was his duty and an honor to join the military.”

Though Gin’s official separation document from the 555th Army Air Service Squadron lists him as a pre-engineering student at UArizona, he switched to pharmacy after being introduced to medicine through his wife, who was a nurse in China. The two met at a picnic for U.S. servicemen stationed there.

After graduating from the university, Gin opened Emery Park United Drug Store, a fixture on the southside of Tucson for 35 years.

“Gung gung worked seven days a week from 9 to 9 because he wanted to make sure he was serving the community,” said his granddaughter Tiffany Wong Grey, using the Chinese word for maternal grandfather.

Wong said her father was appreciative of his education and loved the university. He maintained ties with classmates and faculty, even reaching out to Willis R. Brewer, PhD, the third dean of the college, to ask if his daughter could interview him for a middle school paper on penicillin.

Growth of a college

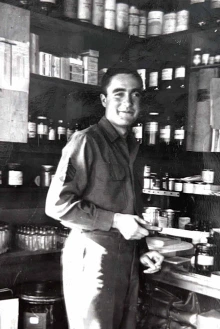

Albert L. Picchioni, PhD, served three years in the Army as a combat medic pharmacist before coming to UArizona to be the College of Pharmacy’s first full-time professor pharmacology.

Photo courtesy of the Picchioni family

Like Gin, Albert L. Picchioni, PhD, also served in WWII. After earning his Bachelor of Science degree in pharmacy from the University of Montana in 1943, he served three years in the Army as a combat medic pharmacist. He worked out of a medicine cabinet in the back of a mobile hospital truck behind the front lines in Germany, Belgium, Austria and, later, the Philippines. Picchioni – “Picc” to his buddies – rarely spoke about his wartime experiences, preferring to spare his family from stories like the time he peeked under a thick, green tarp blanketing the back of a cargo truck only to see endless stacks of soldiers’ bodies.

Picchioni took advantage of the GI Bill to get his master’s and doctorate in pharmacology at Purdue University. Though he had many offers to work in the private sector and at least one other university, Picchioni became the first full-time professor of pharmacology at the university in 1952. It was his first teaching job.

In his 35-year career at the university, Picchioni was an award-winning professor and served as interim dean and associate dean for academic affairs. As a researcher, he studied neuropharmacology in epilepsy as well as toxicology. The Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center, which was the first of its kind in Arizona and among the first in the U.S., started with Picchioni at the helm, providing help in poison emergencies – something that happened with alarming frequency in the 1950s when children got into household cleaning products that lacked chemical information.

Along with other faculty volunteers, Picchioni would take turns answering a 24-hour hotline. Picchioni’s son Joe remembers waking up to the phone ringing in the middle of the night. He’d climb out of bed and peek through the cracked bedroom door to watch his dad work.

“He was like a superhero without a cape,” said Joe, who also recalled testing childproof medication caps.

Picchioni, a beloved professor, wrote some of his lectures at home in a La-Z-Boy chair and always asked to meet students who received the scholarship bearing his name. When Picchioni died in 2012 at age 90, an on-campus memorial service resulted in a VIP list 159 names long.

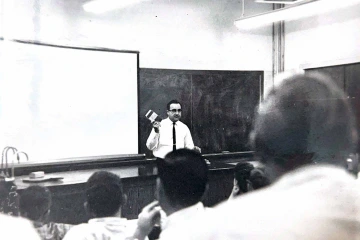

In his 35 years at UArizona, Albert L. Picchioni was an award-winning professor, started what became the Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center and served as interim dean and associate dean for academic affairs.

Photo courtesy of the Picchioni family

Written tributes poured in from colleagues and students, even some who’d never had him as a professor. One of his scholarship recipients wrote that when Picchioni asked to meet her, she fully expected to hear about his work. Instead, he wanted to know all about her.

Classic dad, according to Joe. His father considered students extended family, he said.

Picchioni’s son Geno said he accompanied his dad on several postretirement trips to the college. The elder Picchioni would chat up faculty, asking them about their latest research. No matter what they told him, Geno said, his father always had the same enthusiastic, three-word response: “That is fantastic!”

A fitting reaction, considering the very same could be said of the UArizona Coit College of Pharmacy in its 77 years.