Bringing a precision medicine approach to pain management

While pain is a universal human experience, the mechanisms that produce the sensation of pain in males and females vary in ways that could lead to the development of sex-specific treatments for chronic pain.

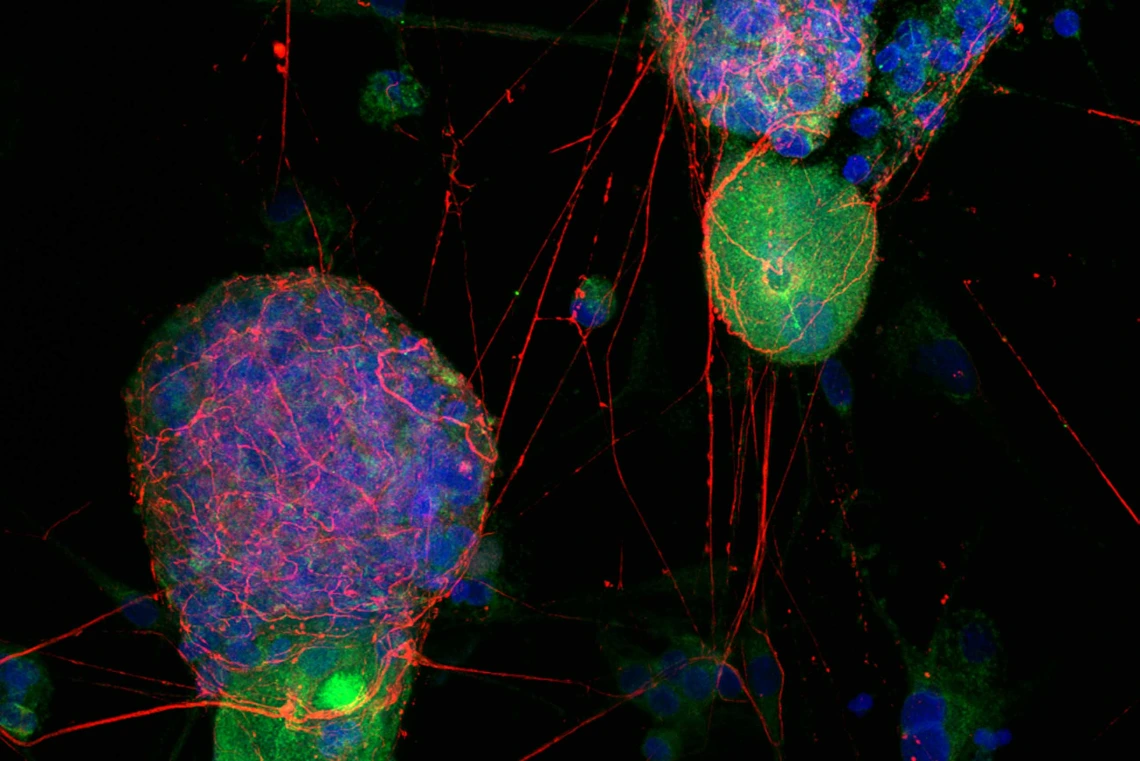

A fluorescent image acquired on a state-of-the-art FV4000 microscope shows many male sensory nerve cells from dorsal root ganglia (green) expressing receptors for orexin (red). Most female neurons (not shown) do not have orexin receptors.

Image courtesy of the Porreca Lab

When it comes to pain and the sexes, the question most people want to know is: who has a higher pain tolerance, men or women? Spoiler alert – scientists don’t have a definitive answer to that question yet; however, thanks to research being done at the University of Arizona Health Sciences, they do know that the sensation of pain is produced quite differently in males and females.

Why does that matter? Because it could lead to new treatments that do a better job of managing chronic pain for millions of people worldwide.

“There is a lot of emphasis on the concept of precision medicine, where doctors take a person’s genetics into account when selecting a therapy. The most fundamental genetic difference is whether the body’s cells are male or female,” said Frank Porreca, PhD, research director for the U of A Health Sciences Comprehensive Center for Pain & Addiction and Cosden Professor of Pain and Addiction Studies at the U of A College of Medicine – Tucson. “That is what we are bringing to the treatment of pain – a precision medicine approach that starts with the basic question: is the patient male or female?”

Tracking the pathway to pain

Research led by Frank Porreca, PhD, significantly advanced knowledge of how pain may be produced differently in males and females.

Photo by Kris Hanning, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

Pain is produced when a stimulus – accidentally hitting your thumb with a hammer, for example – activates nerve cells that send a signal up the spinal cord to the brain where the stimulus is interpreted as the human experience of pain. In the middle of that process is a relay station called the dorsal root ganglion, a collection of nerve cells called nociceptors.

Nociceptors are the specific dorsal root ganglion cells responsible for transmitting signals to the spinal cord. Because of their importance in pain perception, dorsal root ganglia have been a key target for researchers looking to develop new pain therapeutics.

In Porreca’s lab, much of the research focuses on developing novel treatments for pain disorders that are more common in women than in men, including migraine, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, irritable bowel syndrome and others. They have been examining the role of prolactin, a neurohormone best known for assisting mammary gland development and stimulating milk production, in promoting pain in women.

“The answer to why women have more pain may be because female nociceptors have more receptors for prolactin and with high prolactin levels become more sensitive to painful stimuli,” said Edita Navratilova, PhD, an associate professor of pharmacology in the College of Medicine – Tucson who collaborates with Porreca on research into migraine, endometriosis and other female-prevalent pain conditions.

As their research progressed, Porreca and Navratilova started to see something they did not expect – differences in the dorsal root ganglion cells of male mice. Prolactin was acting as expected in female mice, but orexin B, a neurotransmitter that helps promote wakefulness, was showing up in ways no one anticipated in males.

“The first time we saw a male-specific difference was in a model of neuropathic pain, and to be honest, I didn’t believe it,” said Navratilova, who is a member of the Comprehensive Center for Pain & Addiction. “I’m always cautious, but then another person in the lab replicated it, and then another and another. So, it wasn’t just one scientist who saw it. Then I started to believe.”

Prolactin, orexin and the sex differences of pain

Edita Navratilova, PhD, was among the first researchers to notice male-specific differences in the nerve cells responsible for promoting the sensation of pain.

Photo by Kris Hanning, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

Pain is the body’s way of signaling that something is wrong and needs attention. As such, nociceptors are normally activated by high-intensity stimuli that can damage tissue, such as touching a hot stove. Everyone, male and female, will feel pain from a high-intensity stimulus.

Nociceptors also have an amazing ability to adapt to the injury by decreasing their threshold for activation. Suddenly, a low-intensity stimulus like a shirt rubbing on a sunburn now produces pain.

“One of the hypotheses in migraine is that the reason the pain attacks happen is the threshold for activation of nociceptors goes down. If you have a lower threshold to activate nociceptors, then things that shouldn't produce the pain, now do,” said Porreca, who is the associate department head of pharmacology in the College of Medicine – Tucson. “Our prior research showed that prolactin, which is naturally higher in women than in men, lowers the thresholds for activation of the nociceptors, but only in females.”

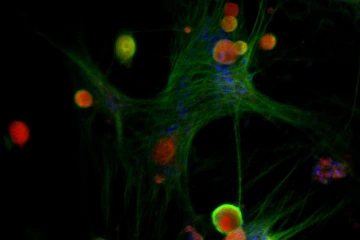

Guided by their expert knowledge of prolactin and the unexpected appearance of orexin B, Porreca and Navratilova designed a study to determine what, if any, role orexin B plays in pain signaling. They used tissue samples from male and female mice, nonhuman primates and humans to test the effect of prolactin and orexin B on nociceptor activation thresholds.

“We found that prolactin only sensitizes female cells and not male cells,” Porreca said, “and orexin B only sensitizes male cells and not female cells.”

Taking the research one step further, they blocked prolactin signaling and then orexin B signaling and examined the effect on the nociceptor activation threshold. As anticipated, blocking prolactin signaling reduced nociceptor activation in females and had no effect in males, while blocking orexin B signaling was effective in males and not in females.

A microscopic image shows the interaction of prolactin receptors (green) with human female sensory nerve cells (red) from the dorsal root ganglion. Male nerve cells (not shown) do not have as many prolactin receptors as female neurons.

Image courtesy of the Porreca Lab

“Until now, the assumption has been that the driving mechanisms that produce pain are the same in men and women,” Porreca said. “What we found is that the basic, underlying mechanisms that result in the perception of pain are different in male and female mice, in male and female nonhuman primates, and in male and female humans. The startling conclusion from these studies is that there are male nociceptors and female nociceptors, and that is something that has never previously been recognized.”

Porreca believes preventing prolactin-induced nociceptor sensitization in females may represent a viable approach for the treatment of female-prevalent pain disorders. Alternatively, targeting orexin B-induced sensitization might improve the treatment of pain conditions in males, including migraine, gout, prostatitis, and others.

Moving forward, Porreca and his team will continue looking for other sexually dimorphic mechanisms of pain while building on this study to seek viable ways to prevent nociceptor sensitization in females and males. He is encouraged by his recent discovery of a prolactin antibody, which could prove useful in females, and the availability of orexin antagonists that are already Food and Drug Administration-approved for the treatment of sleep disorders.

“The outcomes of our study were strikingly consistent and support the remarkable conclusion that nociceptors, the fundamental building blocks of pain, are different in males and females,” Porreca said. “This provides an opportunity to treat pain specifically and potentially better in men or women, and that’s what we’re trying to do.”

Experts

Frank Porreca, PhD

Associate Head and Cosden Professor of Pain and Addiction Studies, Department of Pharmacology, College of Medicine – Tucson

Research Director, Comprehensive Center for Pain & Addiction, U of A Health Sciences

Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, College of Medicine – Tucson

Member, U of A Cancer Center, U of A Health Sciences

Edita Navratilova, PhD

Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacology, College of Medicine – Tucson

Member, Comprehensive Center for Pain & Addiction

Contact

Stacy Pigott

U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

520-621-7239 office | 520-539-4152 cell, spigott@arizona.edu