Five Things You Should Know About Valley Fever

Valley fever, also known as desert rheumatism or San Joaquin Valley fever, is Arizona’s disease.

While rare at a national level, Valley fever is common in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Every year, 150,000 people in the U.S. are infected, and Arizona is home to two-thirds of them. Here are five things you need to know:

1) Valley fever can be a serious respiratory health issue.

While many people who are exposed to Valley fever never show symptoms, those who do commonly experience coughing, chest pain, fever, headache, chills and fatigue. In serious cases, symptoms may last for months and can land people in the hospital. In an average year, 160 people die of Valley fever.

2) It’s often missed or misdiagnosed.

Because the symptoms mimic other respiratory illnesses, doctors often forget to consider Valley fever, even in places where the disease is common.

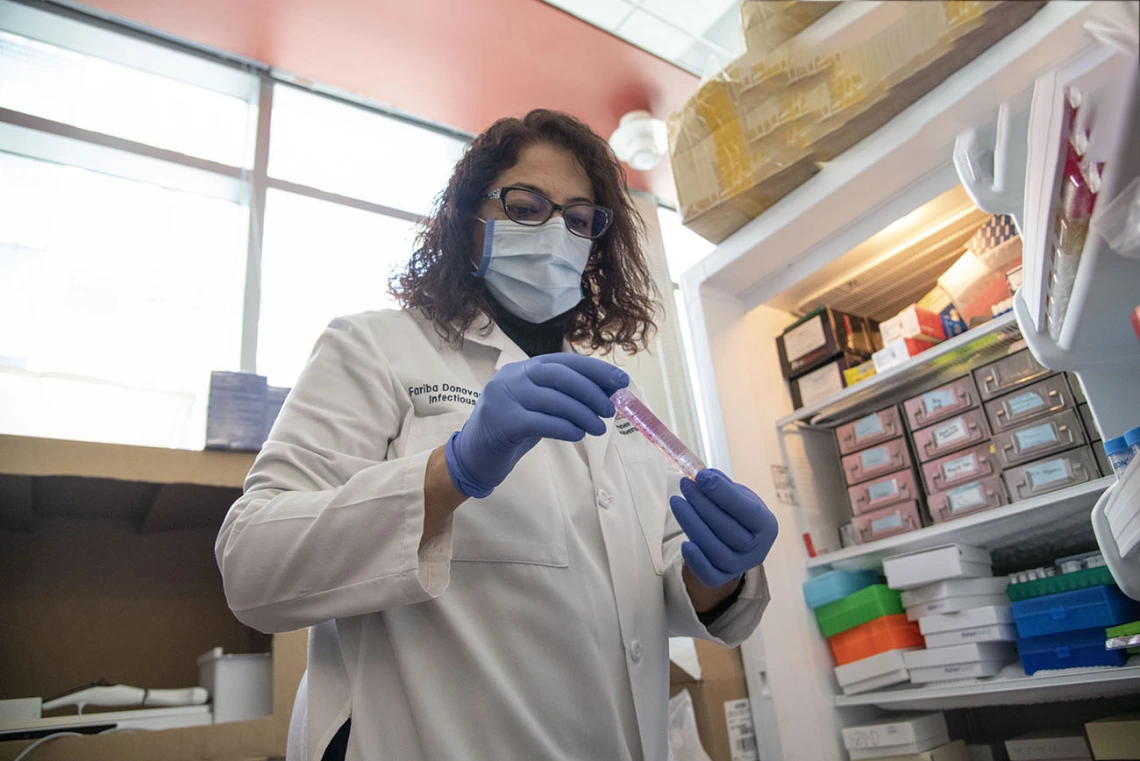

Researchers are working towards a Valley fever cure for animals and people

John Galgiani, MD, founding director of the University of Arizona Valley Fever Center for Excellence (VFCE), and his colleagues found that one-third of all pneumonia cases in Tucson are caused by Valley fever. Other studies have found similar numbers in metropolitan Phoenix.

The Arizona Department of Health Services advises patients who have matching symptoms and have spent time in the Southwest to remind their doctors to check for Valley fever.

3) It’s caused by a fungus.

The culprit behind Valley fever is Coccidioides, a fungus that grows in the soil in places with low rainfall, hot summers and mild winter temperatures. People usually contract Valley fever by breathing in microscopic fungal spores in the air after the soil has been disturbed by wind or human activities. The disease is not contagious.

People can become infected simply by living where the fungus occurs. Construction, agriculture, gardening and other outdoor activities that stir up dust may increase your chances of inhaling Coccidioides spores.

Activities that stir up dust increase the risk of inhaling the Valley fever fungal spores

4) Animals get it, too, especially dogs.

Dogs comprise the majority of Valley fever cases in pets, with Arizona dog owners spending an estimated $60 million annually on diagnosis and care. Livestock and some wildlife, such bats and coyotes, also can suffer from Valley fever.

5) Help is on the way.

Although there’s currently no cure, UArizona Valley Fever Center for Excellence researchers are moving toward a future where the disease is an easily treatable condition for both humans and animals. They successfully tested a possible canine Valley fever vaccine, which serves as a positive sign that a human vaccine could be developed in the future.

UArizona Valley Fever Center for Excellence researchers work on a canine Valley fever vaccine

There is a drug called nikkomycin Z (NikZ for short) that shows promise for treating Valley fever in animals and people. Small studies with NikZ in dogs already have shown positive results and minimal side effects. Researchers are working toward federal approval to conduct clinical trials on NikZ in humans. Their hope is that the drug will be a cure for Valley fever.

More on Valley Fever: Danger in the Dust: Valley Fever

About the Author

The Valley Fever Center for Excellence, located at the University of Arizona in Tucson, was established to address the problems caused by the fungus Coccidioides, which causes Valley Fever. Two-thirds of all infections in the United States occur in Arizona, mostly in the urban areas surrounding Phoenix and Tucson. The Center’s mission is to mobilize resources for the eradication of Valley Fever through education, awareness, patient care and research.