Colleges of Medicine Take Lead on ‘Anti-Racism in Medicine’

Solutions require complex, sustained effort to move the mountain of historical racism in medicine and the systemic ways it may exhibit itself today.

The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed inequities in social determinants of health and wide disparities in health care delivery that are in part tied to historic issues of racism in medicine. (Getty Images)

It’s not an easy topic to confront, but the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix didn’t shy away when a historical photo in its medical museum drew questions from medical students.

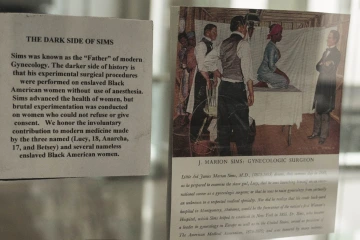

Sonji Muhammad, the college’s equity, diversity and inclusion director for undergraduate medical students, said the image opened a discourse and eventual acknowledgement of the reasons Lucy, Anarcha and Betsey – the women Dr. Sims had “leased” – were there.

“Now, the placard says that because of these women, these advances were able to be brought to light from what they had to endure as enslaved women,” Muhammad said. She recognized the college’s black faculty and staff resource group for their input to ensure the placard addressed the complete history connected to the image.

Catalyst for change

This was only one in a series of incidents over the past few years that prompted the college and the UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson to examine their approaches to addressing racism in medicine. These issues include lack of inclusion or acknowledgment of participation in research (as researcher and subjects), dismissal of medical concerns, and dispelling historical experiences that might account for low vaccination rates among groups underrepresented in medicine.

An image on exhibit in the medical museum at the College of Medicine – Phoenix drew controversy to early gynecological experiments on enslaved women before the U.S. Civil War. Recognition was later added to the description about the women’s sacrifice.

Muhammad said the biggest catalyst for change was the national reaction to the 2020 murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, along with the Black Lives Matter and #SayTheirName movements.

Coming at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic had further exposed inequities in social determinants of health and wide disparities in health care delivery itself, the national movement encompassed medical school campuses, too, said Muhammad and Victoria Murrain, DO, vice dean of diversity, equity and inclusion for the College of Medicine – Tucson. White Coats for Black Lives chapters formed and faculty, students and staff of all races and ethnicities began demanding action, both explained.

Each college took the opportunity to use the movement as a teaching moment. They hosted virtual dialogue sessions or town halls to hear from staff, students, residents, fellows and faculty on what issues might needed to be addressed and how that could be done.

“We had a separate town hall for African-American faculty and students, because the experience is a little bit different. It was raw. It was very, very personal,” Dr. Murrain said. “And there was so much emotion tied with this. You know, there was the whole gamut of anger and frustration, and you name it. People needed that ability to just share those feelings.”

Initiatives and action plans

Both colleges have been recognized nationally for progressively expanding diversity programs. They came up with multipoint efforts and set up task forces and subcommittees to address related issues including recruitment and retention, mentoring, faculty development, curriculum, scholarship, culture and climate, and more.

The College of Medicine – Tucson’s plan has 10 “Anti-Racism in Medicine” (ARiM) themes. The College of Medicine – Phoenix’s involves a 12-Step ARiM Action Plan. For instance, sensitivity, cultural competency and unconscious bias training were added or refined for faculty development as well as resident and fellow requirements, and in the student curriculum.

“This was true before George Floyd’s death. But with social uprisings, I believe other populations began to have more of an understanding of what underrepresented students, especially Black students, go through. To all races and ethnicities, it became apparent change was needed.” —Sonji Muhammad, equity, diversity and inclusion director, undergraduate medical education, UArizona College of Medicine – Phoenix

Sonji Muhammad, equity, diversity and inclusion director, undergraduate medical education, College of Medicine – Phoenix.

“We educate everyone on microaggressions. We educate them on bias, we educate them on confronting bias and what you do about it,” Dr. Murrain said about the College of Medicine – Tucson’s efforts.

The College of Medicine – Phoenix also created electives for fourth-year medical students that focus on inequities of care. And it was one of 11 colleges selected to take part in the Anti-Racist Transformation (ART) in Medical Education curriculum development program through the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai Medical Center in New York City.

In addition, the colleges’ and the University of Arizona Health Sciences Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion provided expanded programming on the topic. Recent offerings include an “Allyship Workshop,” “Shared Shelf Book Club,” “Everyday Bias in Health Professionals Training,” “The State of Black Arizona’s Health and Well-Being of Black Girls and Women in Arizona Report,” and an address by UCLA’s Terence Keel, PhD, on “Human Difference, Nihilism, and the Future of Biomedicine” about the history of racism in medicine.

In a presentation in December, Dr. Keel warned that modern medicine, including broad investigations using genetics and big data, could be considered racist depending upon inherent assumptions or how formulas and equations are configured.

Building a pipeline

“The way we provide health care for people and who we bring on the team to provide and design health care traditionally has been influenced by people able to go to highly selective white institutions that created competitive selection based on attributes focused on the experience of white people,” said Francisco Moreno, MD, Health Sciences associate vice president for diversity, equity and inclusion. “This is not a leftover of anything. This is as much a reality based on what our institutions continue to defend and support.”

Ricardo Correa, MD, diversity director, graduate medical education, College of Medicine – Phoenix

Dr. Moreno said UArizona Health Sciences’ success has been in creating mechanisms to change that reality through pipeline and support programs that bring underrepresented people into medicine and add diversity to the health sciences student body. These programs include the AZ-Hope Ambassadors, Med-Start, Bridge, BLAISER, FRONTERA and P-MAP programs, as well as student support services to ensure the success of these students once they arrive at UArizona.

“Those programs allow us to cast a broader net to motivate and prepare individuals from other decentered backgrounds and marginalized communities to compete for admissions to pre-health and health professions in health sciences,” he said.

And UArizona Health Sciences colleges’ efforts through the Center for Rural Health’s Area Health Education Centers and Rural Health Professions Program allow them to send students out on clinical rotations, research or outreach to underserved communities often identified as educationally disadvantaged. There they can serve as inspiration for future college students.

In addition, since 2019, the PCP Scholarship Program has supported medical students in Tucson and Phoenix with free tuition for those who commit to serving rural and underserved communities in Arizona after their residency training. Most participants hail from areas underrepresented in medicine, added Dr. Murrain.

Demanding change

That’s important because UArizona Health Sciences medical students say they want better diversity in student enrollment and faculty, and improved mentorship that is meaningful to them and their experience.

“This was true well before George Floyd’s death,” Muhammad said. “But with the social uprisings, I believe other populations began to have more of an understanding of what underrepresented students, especially Black students, go through. To all races and ethnicities, it became apparent change was needed.”

Dozens of physicians and trainees with the College of Medicine – Tucson participated in a White Coats for Black Lives demonstration following the death of George Floyd in June 2020. One of the organizers, UArizona surgeon Nfonsam Valentine, MD, far right, told the Daily Wildcat, “It’s finally a recognition of the ongoing disparities and racism and lack of opportunity, and also discontent in the minority community.” (Courtesy of UArizona Department of Surgery)

College of Medicine – Phoenix students of color, as well as resident and fellow trainees, demanded better recruitment of people of color after Floyd’s death in 2020. They wanted this not only among the student body, but also among faculty mentors, too, said Ricardo Correa, MD, the college’s diversity director for graduate medical education.

“The main complaint was, they don’t see people like them,” he said. “Trainees don’t see among higher levels, like the attending physicians, those who look like them. And that triggers a lot of things like being more sensitive, and in how to bring minorities into faculty positions. But we have a big issue regarding diversity and a desire for more diversity and needing more Black physicians in Phoenix. We don’t have enough.”

Dr. Correa underscored the challenge by noting the college authorized hiring a Black physician as lead mentor in that effort, but the position has been open for several months.

“There are challenges in attracting talent,” Muhammad said. “The few underrepresented faculty we have now are asked to do a lot. It’s a toll known as the ‘minority tax.’ People of color are asked to do more on diversity issues because they are underrepresented. That weighs on people.”

Dr. Correa is the perfect example, she said, since he’s asked to do a lot to promote diversity yet is one of only a few Hispanic physicians at the college in downtown Phoenix.

Many steps to right the wrongs

Christian Bime, MD, is a UArizona Health Sciences associate professor in critical care medicine and a pulmonary investigator whose research focuses on acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and biomarkers to explain why Blacks and Latinos are more likely to die from ARDS. He offers another case in point on diversity recruiting. Originally from Cameroon, he was the only Black faculty member in his division when he joined the college in 2013. Today, he’s still the only Black faculty member in his division, he said.

Victoria Murrain, DO, vice dean, diversity, equity and inclusion, College of Medicine – Tucson.

Dr. Bime also is co-chair of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) health equity and inclusion committee. In that capacity, he co-chaired an ATS workshop last summer that reexamined “race correction or race specific equations” used in measuring lung function that is viewed by many as flawed and racist. A paper he co-authored on the subject was published last month in CHEST, the journal of the American College of Chest Physicians.

“It takes a lot of people doing the right things to get the right people in the right places,” Dr. Bime said of preparing future physicians of color. “I did not just pop out of nowhere, right? I was introduced to science in kindergarten. I was mentored by the right people to get into medical school, to graduate and get into residency and fellowship training. And then, I showed up in Tucson, Arizona.”

Christian Bime, MD, associate professor in critical care medicine and a pulmonary researcher at the UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson, was one of the first physicians at the college to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Originally from Cameroon, he said acquaintances in Africa saw the image, as well as news video of him touting the vaccine, and it helped dispel their hesitancy to get vaccinated themselves. (Courtesy of Arizona Daily Star, Rebecca Sasnett)

And just as important as getting people of color into medical careers is building a welcoming and supportive environment, Dr. Bime said. He added it also is important to understand the challenges students, trainees and faculty of color may face and to create structures to support them, especially if they’re first-generation medical students.

“They say diversity gets people through the door and inclusion keeps them,” Dr. Bime said. “The university is doing the best that it can. I sense a lot of good will, good intentions to make things better. There’s a commitment. How successful are we in the short term? A little. We’re still far from where we would like to be, but it’s not easy.”

Problems of racism and diversity, he said, are long-term, societal issues that require a consistent chipping away at the foundations. That’s how you move a mountain.