UArizona Health Sciences Developing Antibody Test That Could Help Fight COVID-19

Immunobiologists aim to use antibody testing to fight the virus that causes COVID-19 and answer lingering questions about the virus.

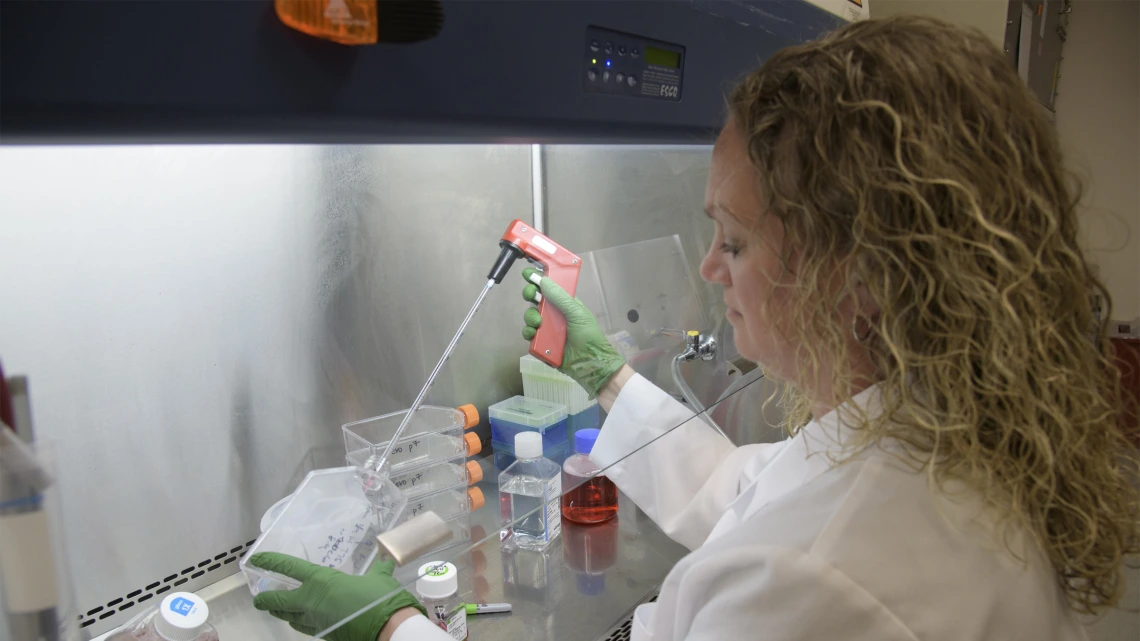

Jennifer Uhrlaub, MSc, assistant research scientist, prepares to culture the virus that causes COVID-19 so it can be pitted against antibodies to learn how it can be defeated.

The virus that causes COVID-19 is new and mysterious, presenting more questions than answers. But University of Arizona Health Sciences immunobiologists are laying the groundwork to answer some of those questions.

Janko Nikolich-Žugich, MD, PhD, teaches immunobiology in the College of Medicine – Tucson, and is chair of the Department of Immunobiology and co-director of the Arizona Center on Aging. Deepta Bhattacharya, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Immunobiology. They lead a team devoted to developing a COVID-19 antibody test, which is different from the test that detects if someone is infected with the virus.

Phases of immunity

Using blood from a local patient who recovered from COVID-19, Health Sciences researchers are developing a COVID-19 antibody test, which will detect evidence of past infection — and immunity to reinfection.

During the initial phase of infection, “first responders” from the innate immune system flood the scene. At this point, by detecting pieces of the virus, the COVID-19 test can identify an active infection.

“The innate immune system goes all the way back to worms and fruit flies, and does its job early on,” Dr. Nikolich-Žugich explained. “It is supposed to shift up to the adaptive immune system, which is made of B cells making antibodies and T cells killing the virus.”

During this later phase of infection, the adaptive immune system deploys antibodies, custom-made proteins that bind to the virus like a key into a lock, marking it for death and persisting in the bloodstream to protect against future infection. A test for these antibodies can identify late phases of the current infection, as well as a past infection.

“Having a test that’s telling you whether you’ve had the disease already, and therefore you’re immune, would be very precious,” Dr. Nikolich-Žugich said.

When COVID-19 becomes deadly

While most people with COVID-19 experience mild or no symptoms, others face life-threatening symptoms.

Makiko Watanabe, DVM, PhD (left), and Janko Nikolich-Žugich, MD, PhD (right), review the results of a preliminary assay that sheds light on the immune response to the virus that causes COVID-19.

“To fend off viral infection, you need to mobilize both the innate and adaptive immune systems. It seems that people who get very severe infections do not upshift to antibody production very well,” Dr. Nikolich-Žugich said.

A patient trapped in the innate immune response is overwhelmed by immune cells attacking the site of infection without the benefit of the antibodies and T cells associated with the adaptive immune response.

They might find themselves caught in a “cytokine storm,” when the virus replicates rapidly and the immune system, struggling to keep up, deploys a surplus of “frontline soldiers” that run amok over the cellular battlefield, harming healthy tissue in addition to infected cells. This uncontained inflammation can cause the lungs to fill with fluid, leading to respiratory problems and possibly death.

“I went into medicine and science to help in a situation like this.”Janko Nikolich-Žugich, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Immunobiology

Although COVID-19’s higher-than-expected ability to hospitalize younger adults has taken many medical professionals by surprise, Dr. Nikolich-Žugich is especially concerned about the novel coronavirus’s outsize risk in older adults, who are most likely to die.

“People who have problems do not upshift to antibody production. We suspect older adults’ immune responses get stuck in low gear,” Dr. Nikolich-Žugich said. “My lab is interested in understanding how and why this happens. We will use this antibody test to profile older and younger adults who have severe or mild infections to understand who has been able to make that shift and who hasn’t, and how we could intervene to boost the immune system.”

Paving the way for treatments and prevention

It typically takes a week to start producing antibodies, but some people take longer. In the case of the virus that causes SARS, a cousin of the COVID-19-causing virus, some people are barely able or are completely unable to mount an adaptive immune response at all. There are some indications that this happens in COVID-19 patients as well.

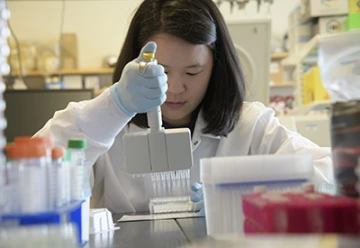

Rachel Wong, Department of Immunobiology research specialist and graduate student, validates the antibody test, which will help unravel the mysteries of the immune response to the virus that causes COVID-19.

For people stuck in this “low gear,” antibodies originating from another person, synthesized in large quantities in the laboratory, might be injected directly into the bloodstream to fight the virus immediately — and data from the antibody test could help identify antibodies that could be mass-produced to treat patients.

“Some people in the community tested positive and are now recovered. Their blood should be rich in antibodies,” Dr. Nikolich-Žugich said. “If we know which antibodies block entry of the virus, and if we can successfully scale them up, they could be used as therapy for the sickest people.”

A vaccine, on the other hand, would protect against infection. Dr. Nikolich-Žugich believes whoever develops a successful COVID-19 vaccine will need to keep the older population in mind.

“Vaccines are typically developed for children and younger adults,” Dr. Nikolich-Žugich said. “In this case, when designing a vaccine, we need to think about older adults, the population that’s most vulnerable.”

The COVID-19 antibody test is an important tool that can provide countless jumping-off points for researchers across the globe, potentially answering questions about the true reach of the pandemic and laying the groundwork for treatments and vaccines.

Laying the groundwork to answer more questions

The antibody test is an important tool that can provide countless jumping-off points for researchers across the globe. Large-scale retrospective community testing could characterize the true reach of this pandemic.

Powerful antibodies could be harnessed to develop lifesaving therapeutics. Knowledge of the immune response could guide the development of vaccines — and might even be combined with what we know about other coronaviruses to produce a universal coronavirus vaccine to guard against future pandemics.

“These times are equally frightening and hopeful. We’re hoping to learn a lot and protect the most vulnerable,” said Dr. Nikolich-Žugich. “This is exactly why I went into medicine and science, to be able to help in a situation like this.”