Reducing COVID-19 Disparities with Inclusive Outreach

Dr. Sairam Parthasarathy leads the Arizona team tackling the pandemic’s outsize effect on racial and ethnic minority communities across the country.

Second-year College of Pharmacy student Lisa Wan prepares to vaccinate a patient against the virus that causes COVID-19.

As the pandemic began to spread across the country, it became clear that certain ethnic and racial minority groups were suffering more from COVID-19. In response, the National Institutes of Health awarded $12 million for outreach and engagement efforts in disproportionately impacted communities. This 11-state alliance is called the Community Engagement Alliance Against COVID-19 Disparities, or CEAL.

Sairam Parthasarathy, MD

“Hispanics, African Americans and American Indians are the most affected by COVID-19,” said Sairam Parthasarathy, MD, chief of the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine in the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson and principal investigator of CEAL in Arizona. “They are suffering more infections, suffering more disease, and a greater proportion are dying.”

In January, the group launched focus groups in Maricopa County and Flagstaff, and started laying the groundwork for focus groups in Pima County. They are interviewing individual community members and administering surveys to learn more about the attitudes and needs of these populations. Ultimately, they hope to learn what people already know about the virus that causes COVID-19 and the vaccine that prevents it, shedding light on where educational efforts and access to care are most needed.

“We’ll be able to understand some of their personal barriers to protecting themselves from exposure or getting the vaccine,” said Dr. Parthasarathy, who is also a member of the BIO5 Institute. “Then we’ll figure out what interventions or solutions we can come up with.”

Sowing seeds of trust

The team hopes to help community organizations address misinformation, build trust and broaden awareness to reduce the overall impact of COVID-19. One key focus has been to educate community members about the importance of participating in clinical trials to ensure vaccines are effective in everyone.

A mobile health unit deployed by the College of Public Health visits El Mirage neighborhood in Phoenix to make vaccination more accessible to Spanish-speaking communities.

Dr. Parthasarathy also referenced historical traumas, such as the Tuskegee syphilis study, in which the U.S. Public Health Service tracked the effects of untreated syphilis in Black men from 1932 until a whistle-blower shared the story with the Associated Press in 1972. Native American, Hispanic and other underserved communities can point to similar injustices in recent history, such as forced sterilizations.

“Some people are fully aware of what a research trial is, but there are mistrust issues,” he said. “They feel they were subject to harm by researchers in the past.”

The fact that these very communities are bearing the brunt of the pandemic, however, highlights how important it is to include them in research efforts to fight COVID-19, he added.

“The hope is that this will catapult the area of health disparities to address more systemic issues.”Sairam Parthasarathy, MD, chief, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine

“It’s important that people of various races and ethnicities participate, so we can more quickly dig ourselves out of this pandemic,” Dr. Parthasarathy said. “This is not the syphilis study. In fact, members of underserved communities will have more to lose if various races and ethnicities aren’t appropriately represented.”

Dr. Parthasarathy shared a story about a clinical trial participant, an underrepresented minority who recently learned he received the vaccine — not a placebo.

“My friend was like, ‘Wait a second, I got vaccinated back in October before any of you were vaccinated!’ All along, he’s been immunized,” Dr. Parthasarathy said. “This individual had the advantage of being vaccinated way before any of us. That’s one of the perks of participating in a trial.”

Rooting out health disparities

Dr. Parthasarathy says preliminary data in Arizona, which have not yet been published or peer-reviewed, show that COVID-19 hospitalization rates are disproportionately high for Hispanic, Black and Native American patients, and that COVID-19 mortality rates are disproportionately high for Hispanics and Native Americans. When clinical trials for vaccines were getting underway, however, the hardest-hit communities weren’t initially well represented in this research.

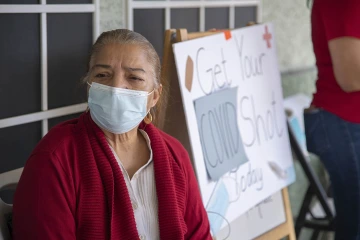

Getting vaccinated protects from infection with the novel coronavirus.

Dr. Parthasarathy says early recruitment efforts were made in affluent neighborhoods, but thanks to outreach efforts like those spearheaded by CEAL, the Pfizer and Moderna vaccine trials improved diversity in enrollment, and have received praise for recruiting Black and Hispanic participants in numbers that better reflect their proportion in the U.S. population.

Dr. Parthasarathy says he hopes the pandemic, for all the tragedy it has caused, will have a “silver lining” of forcing a societal reckoning with health disparities, which COVID-19 has cast in a harsh light.

“The pandemic is killing people at a very visible and apparent rate. Social determinants of health are driving the increased risk, making you more likely to catch COVID and die. The connection is more immediate. That tension is greater,” he said. “The hope is that this will catapult the area of health disparities to address the more systemic issues — and find some solutions to long-term problems that have been alienating those sectors of society.”