What Is Design Thinking?

In the fall, students will be able to dive headfirst into design thinking, a creative process for solving real-world problems.

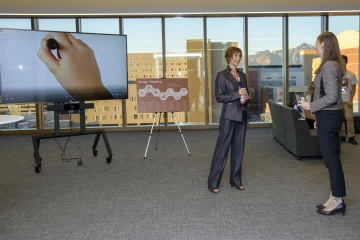

Kasi Kiehlbaugh, PhD, left, will launch a hands-on class in design thinking, which will bring many minds together to nurture collaboration.

With the fall 2020 launch of a new University of Arizona Health Sciences course open to all UArizona students, the university is poised to join a handful of other higher-education institutions that offer programs in design thinking. Designed by the founding faculty members, Health Sciences design Program Director Kasi Kiehlbaugh, PhD, and Winslow Burleson, PhD, the class will introduce students to a creative problem-solving approach that empowers them to break away from passive lectures and dive headfirst into actively solving real-world health problems — including those resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Students also will learn how to collect and analyze qualitative data, often dealing with the logistical and emotional aspects of an individual’s experience. Students coming from STEM fields, who are accustomed to immersing themselves in numbers-driven quantitative data, might learn new ways of viewing the world through the “people-first” design-thinking process.

A program in design thinking makes its home on the sixth floor of the Health Sciences Innovation Building.

The class will bring students together on the sixth floor of the new Health Sciences Innovation Building, in a large open classroom with mobile carts, breakout rooms and a makerspace equipped with 3D printers, computer numerical control (CNC) machines, laser cutters and other rapid prototyping equipment — a playground for anyone who wants to create actionable solutions to today’s health-care challenges. The students will also be exposed to sketching and improv to get them comfortable sharing their ideas, and hear from guest speakers who will shed light on a variety of perspectives.

Interdisciplinary and collaborative

Kasi Kiehlbaugh, PhD, brings her background in engineering to the Health Sciences campus, where she will oversee transdisciplinary teams solving tomorrow’s medical challenges.

Although the Health Sciences campus will be the hub for the new program, it is intended to attract students from every corner of campus, nurturing valuable academic diversity.

“The thing that really distinguishes this program from more traditional curriculum is the focus on training our students to think differently,” Dr. Kiehlbaugh said. “We’re changing the way they will approach challenges they’ll encounter in their professional lives, particularly when they work on interdisciplinary teams.”

Exposure to ideas outside of their own majors can help students break out of entrenched ways of thinking, bringing them into contact with people from across disciplines — as well as patients, caregivers and other community members whose lives might be improved by students’ work.

“I have seen what a catalyst it can be when you bring people together who have different backgrounds,” Dr. Kiehlbaugh said. “When we interface with people who are trained to see the world differently and think differently, new and exciting things happen.”

No matter what field graduates enter, they’ll be ready to tackle any problem that comes their way — an important skill to have when no one knows what the future will bring. In fact, as the medical community continues to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, students can get a head start on cultivating agility in the face of uncertainty, perhaps by developing and testing novel ways to decontaminate surfaces, designing and producing personal protective equipment and nasopharyngeal swabs, or exploring processes to conduct large-scale contact tracing. Responding in real time to a rapidly evolving crisis can help them think quickly on their feet when they face similar situations in their professional lives.

“We don’t know what the future looks like,” Dr. Kiehlbaugh said, “but we’re equipping students to enter the future with confidence.”

Education for the future

Design thinking represents a shift in how educators conceptualize how best to prepare students to enter their careers with confidence and competence.

“We have a fairly large space,” says Winslow Burleson, PhD. “It can be flexible and improvisational to support the different needs of the learners.”

By learning new ways of thinking, rather than focusing on discrete skills, students will emerge from the program with a strengthened aptitude to adapt, to collaborate, to think — skills they will need no matter what field they enter, no matter what twists and turns their industry undergoes in the coming decades.

“Their desire to meaningfully contribute is generally what brings students here in the first place,” Dr. Kiehlbaugh said. “With the training they receive from the Health Sciences design Program, they will have developed the mindsets to identify and tackle challenges.”

“We want to create an ecosystem to elucidate design thinking across the university and with community partners,” Dr. Burleson added. “This will encourage students to break down and transform many of the silos that have traditionally been encountered.”

Whether they’re improving quality of life for their grandparents or responding to sudden outbreaks of emerging diseases, students need to be adaptable and able to think outside the box. The future might be a mystery, but one thing we know for sure, now more than ever, is that students must expect the unexpected — and know how to confront it unflinchingly.