Building a Better Lab, One Cup of Joe at a Time

For the College of Medicine – Phoenix’s Dr. Taben Hale, sharing the success of those she mentors comes with the territory.

Taben Hale, PhD, says her curiosity drove her to try a lot of things when she was a child, and that curiosity also led to her life’s work.

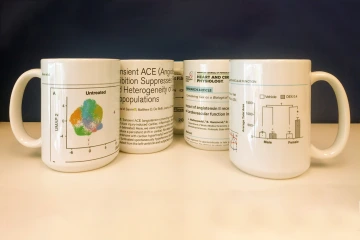

Can a cup of coffee be a symbol of pride? It can be if that coffee mug has the title page of your first published research paper.

To celebrate a postdoctoral student’s first publication, Dr. Hale has coffee mugs made with the cover page and relevant charts. She gives one to her student and keeps one as a memento. (Photo courtesy Taben Hale)

“It’s just a little something that they can walk around and share without being boastful. You’re just drinking your coffee,” she said with a smile. She has one mug made for the student and a second for her office. “I look forward to my shelf being full of these mugs sharing these successes.”

That celebration of success is one of the traits that drives Dr. Hale. As a fourth-year undergraduate, “she was already functioning like a grad student,” said Michael Adams, PhD, a professor in the Department of Biomedical and Molecular Sciences and director of the Bachelor of Health Sciences Program at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. “It was hard to really realize she wasn’t a grad student. I think in her first year in our lab she was mentoring undergrads.”

That interest in mentoring continues to this day. “Dr. Hale is an exceptional mentor, and you could not be in better hands,” said Rebecca Fisher, PhD, the interim co-chair of the Department of Basic Medical Sciences at the College of Medicine – Phoenix. “She is patient, generous with her time, and she will be there for you throughout every step of your career.”

A curious child

Growing up outside of Toronto, Dr. Hale said she was into everything. “I really liked sports. I played flute. I liked drama. I liked science. I mean, I liked everything!” she said. “And my poor parents who had to drive me to everything! I was in ballet for many years. So I would be in ballet, flute, basketball in the winter, soccer in the summer. And now that I am a parent, I think, oh my, I can't believe they let me do all those things. It must have been terrible for them having to go drive me all over town.”

Dr. Hale initially considered going into business, like her father. But an interest in pharmacology led her to Queen’s University’s life sciences program. The numerous pre-med classes intrigued her, but one experience in a research laboratory changed her outlook. When she saw how an injection of epinephrine increased blood pressure and heart rate, she was hooked. Enter Dr. Adams and his research on hypertension.

“I know that my trainees and my staff are going to get a lot of attention, support and mentorship, and that's really important to get to make sure you get to where you want to be in your career.”

Taben Hale, PhD

“He was and still is an incredible mentor, really enthusiastic, really passionate about teaching and about research,” she said. “I ended up staying in that lab to do my PhD. I wanted to be Mike Adams. I saw that he had a family, and he would be at his kids’ soccer games, and he would travel, and he made it look easy. I did see grant writing and the work, but he did make it look fun. He did make it seem like this is the kind of job I would like.”

Mentorship is a critical focus

Following in Dr. Adams’s style, Dr. Hale is serious about mentorship and support.

“I can't understand the people who have these really competitive environments, because you need people to be comfortable telling you when things don't work or your hypothesis is not supported by the data,” she said. “The other thing that's really important to me with respect to trainees is their success. I'm really proud of how successful those in my lab have been at obtaining awards and fellowships, presentation awards at conferences, and funding for their own research. And then the careers they go on to after the lab. This is a training environment. I really work with them to make sure that we're meeting their goals, as well. I know that my trainees and my staff are going to get a lot of attention, support and mentorship, and that's really important to get to make sure you get to where you want to be in your career.”

Bobbie Garvin has been a postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Hale’s lab for the past five years. She said the support she has received has helped her obtain an assistant professor position at East Carolina University starting in January. “She has supported this upcoming move by challenging me to push outside of my comfort zone, pursue novel research ideas and work to improve my skills and build my professional network. Most importantly, she helps me do this by modeling it herself,” Dr. Garvin said. “She has acted as my advocate and sponsor every step of the way – always supplying critical feedback on my work and obtaining opportunities on my behalf. I am so fortunate to have found a mentor like Dr. Hale because I know that when I move on from the College of Medicine-Phoenix, she will continue to serve in this capacity.”

“I think probably the No. 1 thing that matters the most is she is incredibly trustworthy,” Dr. Adams said of Dr. Hale. “She has integrity. She is not after anybody else's work. She's not trying to take better accolades than somebody else. She's a collaborator.”

Dr. Hale works with research technician Dana Floyd in the Hale Lab at the College of Medicine – Phoenix.

That collaborator mindset allowed Dr. Hale to gain research expertise across a broad spectrum of topics, according to Christopher Glembotski, PhD, associate dean for research and director of the Translational Cardiovascular Research Center at the College of Medicine – Phoenix.

“That's one of the things that's refreshing about her and her research, is the perspective she has is broader than most,” Dr. Glembotski said. “For example, people in our field get put into categories – if they study the heart, like I do, or they study the blood vessels, or even sometimes the blood and cholesterol . And she studies all of those areas. She's a vascular biologist and a cardiac biologist, which is unusual. She also studies the differences between the sexes in their susceptibility to various diseases, including heart disease. Some of her most fascinating work is studying the way the different sexes respond to, say, environmental stresses differently, and then how that can somehow become imprinted leaving a molecular memory that can continue to affect the cardiovascular system even after the stress has subsided.”

Polar opposites

Dr. Hale’s wide-ranging research interests have her looking at both ends of the cardiovascular disease lifespan.

“We know people with high blood pressure often don't know they have it, so it can be many years before they're treated,” she said. “In response to high blood pressure, the heart has to pump harder against a higher resistance to blood flow, so the heart gets bigger. Associated with that increase in size, there can be an increase in scar tissue called fibrosis – which makes the heart stiffer and less able to pump blood as effectively. We have shown that we can change the cells that produce the scar tissue so that they kind of reset, so they're less active and are less prone to cause fibrosis.”

The other project is a collaborative U54 grant with Colorado State University, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard University. They are looking at the early drivers of future disease risk and how things that happen in utero, such as prenatal stress, may set the stage for future cardiovascular disease and major depression.

As the new director of WIMS, Dr. Hale wants to expand the reach of the group’s programming into actionable items so that more women scientists are cited and celebrated for their work.

“If someone has a success, we'll share it on Twitter, and then we can amplify it for each other, even for colleagues who are not necessarily in in the same field.”

While Twitter fame might be more fleeting, a coffee mug can last forever.