Connecting with Sarver Heart Center’s Hesham Sadek

Director wants to lead Sarver Heart Center to top 10 ranking while finding ways to repurpose drug therapies for rare disorders.

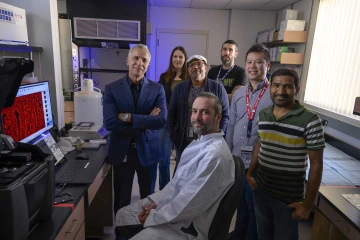

Hesham Sadek, MD, PhD, runs a very active research lab in addition to leading the Sarver Heart Center and College of Medicine – Tucson’s Division of Cardiology.

Photo by Kris Hanning, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

There is a proverb that says necessity is the mother of invention. For Hesham Sadek, MD, PhD, director of the Sarver Heart Center and chief of the Division of Cardiology at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson, necessity, in some cases, is what happens when a physician is faced with a patient who has puzzling symptoms and the doctor’s scientific nature kicks in to try to solve the problem. That desire to get at the heart of an issue is one of the bridges between the clinical and research aspects of his role.

Health Sciences Connect caught up with Sadek to learn more about his goals for the Sarver Heart Center, his interest in rare cardiovascular disorders and how illnesses impact patients beyond the physical.

You joined the College of Medicine – Tucson and the Sarver Heart Center in 2024. What inspired you to take the role?

What intrigued me about the university was several things: One is the very rich history of the Sarver Heart Center. For example, example, the first federally authorized use of an artificial heart as a bridge to a human heart transplant was done here at the U of A, as well as life-saving compression-only CPR, which is now adopted by the American Heart Association and implemented worldwide as a lifesaving measure, was spearheaded by U of A cardiologists at the Sarver Heart Center. Also, the total artificial heart — the SynCardia Total Artificial Heart — was spearheaded here by Marvin Slepian, MD, JD, who is also a member of the Sarver Heart Center. After I visited, I realized there‘s an incredible group of talented scientists and physicians in my field, sarcomere biology. We probably have the most elite researchers in the field here. There’s this spirit of wanting to do something important for the community and for the patients, to discover and build something, which was very palpable when I visited.

As an administrator, what do you miss about your previous roles?

Well, I hope that I won’t be an administrator only as I am still a clinician and run an active lab! I have big NIH grants and continue to publish papers. Half of my lab has already transferred, and the other half is coming in January. I plan to squeeze in an extra 15 hours a day.

What are your goals for both the Division of Cardiology and the Sarver Heart Center?

The goals are the same and they’re different. I view the Sarver Heart Center as the home of clinicians and researchers who work on cardiovascular disease, for students and trainees, and as our brand for cardiac research and clinical care nationally and internationally. Typically, we all use this phrase “bench to bedside,” but it might not mean anything, because it’s really difficult for an investigator or even a research institute to bring therapies to the clinic. It can cost over $2 billion and take 10 to 15 years to bring a drug to the market. There’s really an opportunity here at the Sarver Heart Center and the Division of Cardiology to change that. There is an active clinical trial unit in the Sarver Heart Center, which we are revamping and trying to restructure to bring in more cutting-edge clinical trials, specifically in gene therapy.

Hesham Sadek, MD, PhD, director of the Sarver Heart Center, (left) stands with members of his team including (from back left) Tara Tassin, PhD; Waleed Elhelaly, PhD; Gonzalo Gancedo Alonso; Nicholas Lam, PhD; and Sailu Sarvagalla, PhD. Seated is Ivan Menendez Montes, PhD.

Photo by Kris Hanning, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

I also came to build a platform of personalized medicine, specifically using repurposed drugs and naturally occurring molecules to target some of the rare cardiovascular disorders to help patients who are not going to be treated or targeted by drug companies otherwise. Some of these rare disorders are neglected, not intentionally, but because it’s really difficult to make a drug that affects maybe a few hundred or a thousand patients.

I want to take this opportunity to thank James Liao, MD, the chair of the Department of Medicine, and Michael M.I. Abecassis, MD, MBA, inaugural Humberto and Czarina Lopez Endowed Dean iof the College of Medicine – Tucson, for choosing me for this important role. I told Dean Abecassis when he hired me, that I plan to make this one of the top 10 cardiology divisions in the country within 10 years. I think that this goal is achievable, given the immense talent within the Cardiology Division.

Additionally, our clinical excellence, supported by a strong partnership with Banner Health, supports this vision. Banner has been instrumental in enhancing the quality, complexity and volume of procedures we perform, including heart transplants, mechanical assist devices, bridges to recovery and complex cardiac interventions. We have that already in interventional cardiology and electrophysiology. We have new subspecialties such as cardio-oncology, for example, an interface between oncology and cancer therapeutics and cardiology, as well as cardiac genetics. We’re building a new section on cardiac genetics and bringing in experts from around the country to run that who will also address rare genetic disorders in the heart.

From the clinical standpoint, we’re also trying to revamp and build a larger cardiac rehabilitation program and women’s cardiovascular health program, as well as a complex chest pain clinic and a program to treat patients who have intractable chest pain and severe coronary heart disease.

You talked about the rare or “orphan” cardiovascular disorders and cardiogenetics together. What are your plans around this?

Cardiovascular genetics on the clinical side deals with patients with rare genetic disorders. As it stands, there are not a lot of therapies. But these patients and their families need to be taken care of. They need to undergo genetic testing and get genetic counseling. They need to be placed on therapies earlier on, rather than later, because it makes a big difference in the reversal of the disease. There are a lot of things that we can do for these patients. Once they develop heart failure, if it’s direct cardiomyopathy, we plan to build a strong cardiac transplant program, which is critical for our community. This is an important point — to have a strong transplant program that serves our community.

What was one thing you wished you knew when you were in medical school that you know now?

I wish that medical schools would teach the impact of illness on patients. I think as physicians it’s easy to be mechanical about it. In some ways, you do have to be a bit disconnected so that you are able to treat the patient. It’s something that you learn over time. How diseases affect patients and families. How patients who are affected by diseases that don’t have therapies become desperate. And how important it is for the physician to be there for them. It is also important for physicians to realize that their role can extend beyond just administering treatment or providing support for the patient and families. That as physicians we have an obligation to contribute to medical science. Sometimes it is a as simple as reporting a rare case, but sometimes it is by devoting decades of your life to finding an answer for your patient’

It’s also important to realize the role academia plays in pushing the boundaries of medicine and discovery. We are privileged as physician-scientists to be in that position where we can see a patient in the clinic and then come back to the lab and try to do something about their illness, try to study it, try to find something.

Many of the biggest discoveries in our history have been made by physicians who saw something in the clinic, came back to the lab and tried to solve it. With the economics of medicine and difficulty in funding, it’s easy to see how that side of medicine is not a priority anymore. And this is one of the things that attracted me to this place, honestly, is that this is a priority here. That building and strengthening of that type of physician-scientist, and building bridges between physicians and scientists, and between the clinic and the bench, is crucial.