Nursing’s founding mothers were devoted to research

First deans pushed for school’s founding to counter a shortage of nurses and stimulate the profession’s growth in Arizona.

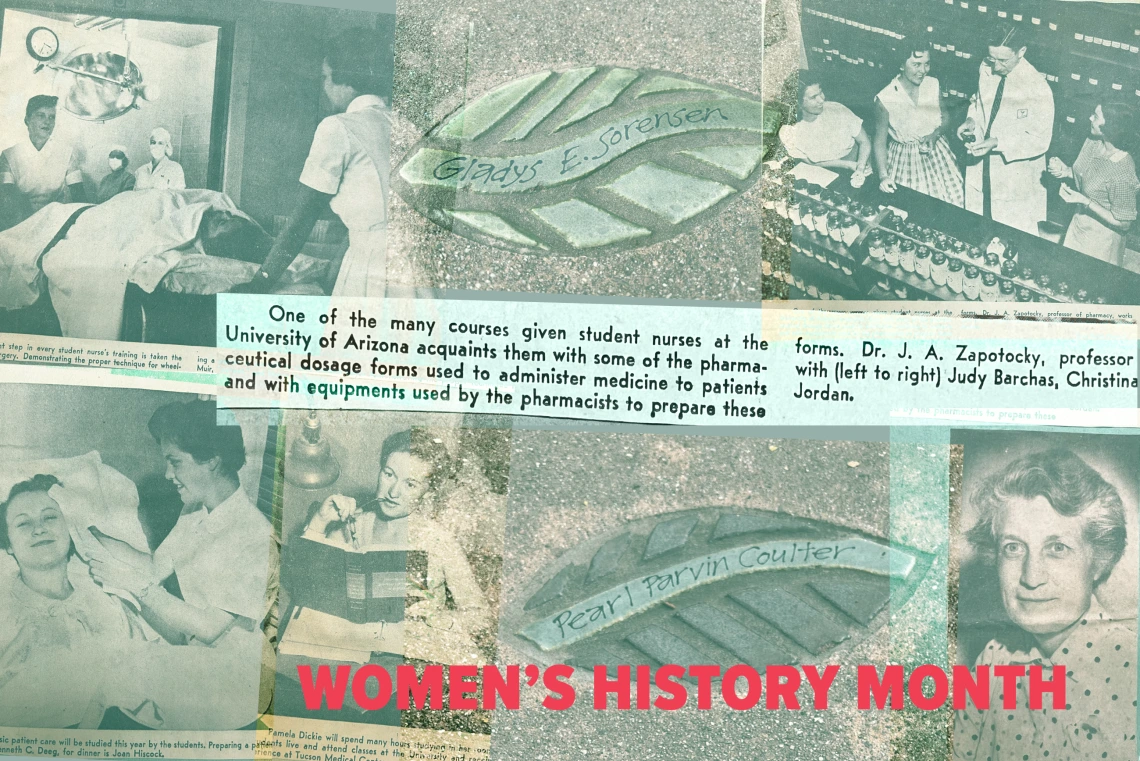

Arizona Daily Star clippings from the 1950s highlight the early days of student life at the U of A College of Nursing.

Photo illustration by Xinyu Zhang, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

You’ll find the green, ceramic leaves bearing the names of Pearl Parvin Coulter and Gladys E. Sorensen embedded in the sidewalk at the southern end of the University of Arizona’s Women’s Plaza of Honor.

They’re across from each other and perfectly aligned. That’s appropriate considering that’s also how the pioneering deans of the University of Arizona College of Nursing ran the program. Its founders recognized the need not just for patient care but also for nursing research and teaching. They set the wheels in motion for the college’s advanced education programs.

Pearl Parvin Coulter was the first dean of the U of A’s College of Nursing.

Photo by University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus

These forward-thinking women propelled the college to what it is today: the top bachelor of science nursing program in the state, with not one but two distinct programs — a conventional pathway in Tucson and an integrative health pathway in Gilbert.

Coulter, who led the nursing school — it didn’t become a college until 1964 — from its start in 1957, was the U of A’s first female academic dean. When she retired in 1967, she turned the reins over to Sorensen, who came to the U of A in 1958. Even after Sorensen’s retirement in 1986, she remained engaged with the college until her death in 2021.

Terry A. Badger, PhD, RN, who was hired by Sorensen and has been part of U of A Nursing for more than 30 years, called Sorensen “a visionary leader for her time.”

“She was a committed nursing leader who, even after retirement, volunteered her time and talent to the college,” said Badger, the Eleanor Bauwens Endowed Chair of Nursing, the college’s interim associate dean for research and a professor of psychiatry.

It was during Sorensen’s tenure that the college experienced massive expansion and the establishment of specialty and advanced degree programs.

“Without their visionary work to push for the foundation of first the school and then the college, the outstanding research being conducted by our faculty today might not have happened,” said Brian Ahn, PhD, dean of the College of Nursing. “We owe a debt of gratitude for everything they did to make this a reality.”

A new program

Much like today, there was a nursing shortage in the United States in the 1950s. In her 1960 paper titled “Nursing in Arizona,” Coulter mentioned the 1950 U.S. Public Health Service “Survey of Nursing Needs, Resources and Supply in Arizona” that cited the nurse deficiency and need for nursing education here. Yet, in 1955 Arizona was the only one of the then 48 states without a baccalaureate nursing program. That changed two years later when the U of A’s School of Nursing opened. Tucked into the College of Liberal Arts, it had 42 students in that first class and 20 graduate nurses, according to an Arizona Daily Star article.

Gladys E. Sorensen took over from Coulter and guided the College of Nursing from 1967 until she retired in 1986.

University of Arizona archives

By the time Coulter was named professor and director of the new U of A School of Nursing, she already had 20 years of experience teaching public health and had been head of the Public Health Nursing Section of the then-University of Colorado School of Nursing. She advocated for university educations and higher degrees for nurses.

She got a late start herself. While Coulter dreamed of becoming a nurse, her father wanted her to go to college. That was uncommon at the time as nurses typically went through a diploma program, a hands-on vocational training program that doesn’t require a college education. Coulter appeased her father by going to school for a few years and then teaching. She earned a degree in biology and then a Master of Science in Colorado, where she met her husband. After he caught pneumonia and died, Coulter followed through on her desire to become a nurse.

In the second year of the nursing school’s existence, Sorensen came on board, joining Coulter and just a few other faculty, she said.

“Tucson was small enough that you knew a lot of people and either students or the students’ parents or other faculty members you’d run into when you went places,” Sorensen said in a 1995 Arizona Historical Society oral history project.

Coulter was adamant that the College of Nursing be an independent, freestanding college, Sorensen said in the oral history interview.

When Coulter retired in 1967 and Sorensen succeeded as dean, ground was broken on the new College of Nursing building. The program — with a master’s degree freshly approved — had outgrown all of its previous quarters, which at one point included the stadium, then a real estate office on East Sixth Street and the bottom of the new home economics building.

“Mrs. Coulter always called it the basement,” Sorensen said in the 1995 interview. “She wanted them to be sure they, the university administration, knew it was the basement so they’d feel sorry for us and eventually give us something else.”

“Growing by leaps and bounds”

When Marylyn M. McEwen, PhD, was accepted into the College of Nursing for a bachelor of science in nursing in 1972, Sorensen was setting the stage to recruit high-level faculty in preparation for a PhD program, one of Coulter’s goals.

Dean Gladys E. Sorensen was at the helm when ground was broken in 1967 for the U of A College of Nursing building.

University of Arizona archives

Around that time, nursing enrollment at universities across the country shot up. Sorensen recalled in that ’95 interview that she went to lunch with university administrators to ask for 10 additional faculty members to accommodate the influx of students. They initially told her no. When Sorensen said enrollment would have to be limited, they relented.

“They informed me I was the most expensive dean they had taken to lunch because nobody had asked for that much when they were talking about what the needs for the college were,” Sorensen said. “There was just a period in there when it seemed like nursing was growing by leaps and bounds.”

The PhD program became a reality in 1976, the year McEwen, a professor emerita of nursing, graduated. McEwen landed a clinical nursing position in the old county hospital, but she said she knew she wanted to be part of the innovative programming happening at the U of A someday.

McEwen only had brief encounters with Sorensen, who was dean during her time as an undergraduate and in the master’s program. But when McEwen was working on her doctorate, she said she would often run into Sorensen. The dean was always eager to hear about McEwen’s research on decreasing diabetes and health disparities for Mexican Americans living in the border region as part of the Southeast Arizona Area Health Education Center. McEwen went on to become the Gladys E. Sorensen Endowed Professor in Nursing, which she called “an incredible honor.”

“I was so in awe of her position, her leadership and the sustainability of her work,” said McEwen.

Even well into retirement, Sorensen, who held leadership positions in numerous nursing associations, including as president of the American Academy of Nursing, was still working to further the future of her field.

“One day I was meeting her for lunch. We were chatting, and she said she’d just finished a letter for the American Academy of Nursing,” McEwen said. “She said, ‘There is an issue that I just had to respond to.’ She was in her 90s, and she was still going strong. She was a force to be reckoned with. She was an amazing leader.”