Safe Zone Trainings Help Build an Inclusive Health Workforce

The Health Sciences Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion promotes increased awareness of LGBTQ+ issues with activities that cultivate empathy.

Matt Peters uses a Safe Zone placard to signal an inclusive work environment and spread awareness of training opportunities.

Across Drachman Hall, workspaces were intermittently decorated with signs emblazoned with a bright pink triangle; light blue and pink stripes; and rainbow squares. They were enough to pique the interest of a program coordinator named Matt Peters.

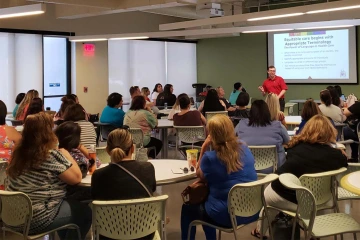

Chris Sogge, College of Nursing academic advisor, leads a Safe Zone inclusive health care workshop at Banner – University Medical Center, where more than 1,500 people have received this training.

Peters learned about Safe Zone workshops, designed to cultivate a safer, more inclusive atmosphere for LGBTQ+ people on campus. He quickly signed up.

“So much of our education and scientific research is moving toward collaborative models,” Peters said. “The more we connect with people who have been excluded in the past, the better off our world is, and the better off all of us are.”

While Safe Zone workshops are available on main campus and from the College of Medicine – Tucson, the University of Arizona Health Sciences Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion offers LGBTQ+ Safe Zone training specific to the larger Health Sciences community in Tucson.

“A climate that is inclusive for all, where people feel a sense of belonging, is important, especially in a health care setting,” said Lydia Kennedy, MEd, senior director of the Health Sciences Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. “As I say in the trainings, ‘You’re in the business of healing, not hurting.’”

Opening closet doors

After introductions, a facilitator reads questions from the Heterosexual and Cisgender Questionnaire: “When and how did you first decide you were heterosexual? What did your friends say when you told them? When did you first realize your gender identity matched the sex you were assigned at birth?”

Kennedy says this exercise helps participants outside of the LGBTQ+ community understand the burden of fielding potentially intrusive questions so frequently.

“You’re in the business of healing, not hurting.”Lydia Kennedy, MEd, senior director, Health Sciences Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

“It’s eye-opening for a heterosexual or cisgender person to experience the microaggressions faced by people from LGBTQ+ communities on a regular basis,” Kennedy said. “Most recognize that the impact these questions have on people can be jarring. It can be such a negative experience rather than a beautiful, affirming experience.”

One popular exercise shows participants how their reactions can make someone else’s coming-out experience positive or difficult. Everyone begins with a paper star, each point symbolizing their family members, friends, communities, and personal and professional goals. Depending on the color of the paper, participants may have to fold or even tear off the points of their stars, letting the pieces fall to the floor to symbolize how a lack of support can leave someone’s life in pieces.

“During the Coming Out Stars exercise, some folks were completely accepted through the whole process and didn’t have any creases. Some folks have some creases, and those creases leave scars. And you have some whose stars are ripped up completely,” Kennedy said. “Sometimes people cry, sometimes people have mixed emotions about the exercise.”

Even in the Zoom era, after sending participants stars to print out and use on camera, the team found the exercise still packs a punch.

“It was very eye-opening and gut-wrenching,” said Lindsay DeWolfe, BSN, RN, PCCN, a College of Nursing graduate student who attended a training for health care providers in March. “We were also lucky enough to have a few brave souls share their personal stories, which brought many to tears.”

By putting participants in the shoes of marginalized individuals, Safe Zone underlines experiences that are deeply felt by some but invisible to many.

Logan McDermott, a rising second-year PharmD student who participated through the student orientation the College of Pharmacy offered in August 2020, said the material validated her own experiences.

“People like me have lost close connections among their friends and family, have been kicked out of housing, have not received medical care, have been fired or denied job opportunities, and even have died because we were not accepted,” McDermott said. “It was the first time some of the students truly began to understand how someone who identifies as LGBTQ+ walks through life. It was an incredibly moving experience to see students in my cohort moved by the materials presented.”

Creating an inclusive culture

In breakout sessions, Safe Zone participants go over a case study relevant to their disciplines. For example, pharmacy students learn about a pharmacist in Phoenix who refused to fill a prescription for a transgender customer, and nursing students learn about an oncology nurse in Tucson who provided substandard care to a gay patient.

Cases like these are reminders of health care providers’ power to create positive or negative experiences for patients, some of whom are already navigating challenging situations. Kennedy says too many negative experiences can drive LGBTQ+ people away from the health care system, exacerbating health disparities, whereas positive experiences allow them to feel safe seeking care.

A participant speaks at a 2018 UAHS LGBTQ+ Safe Zone workshop.

“Seemingly small changes — like updating intake forms so there are more options than ‘male’ and ‘female’ for gender, or adding a section for a preferred name — can have an enormous positive impact on members of the LGBTQ+ community by making them feel welcome and heard,” said Elizabeth Pepper, MEd, formerly the student services coordinator for the College of Pharmacy.

By putting participants in the shoes of marginalized individuals, Safe Zone underlines experiences that are deeply felt by some but invisible to many. It is a gateway to an atmosphere in which everyone can thrive.

“After the event, I felt a sense of safety to be my authentic self with other students and faculty. It was a significant weight off my shoulders,” McDermott said. “We need to reach a more inclusive, accepting and equitable world, and this is a step in the right direction.”

One of the same placards that first caught Peters’ eye now hangs outside his cubicle in the Health Sciences Innovation Building. He hopes it will spark similar interest in others, and signal to passersby that there are allies on the Health Sciences campus.

“I hope my sign has benefitted others,” he said, “even if all it offered was a small reassurance that there are Wildcats among them who are actively working to create a more inclusive and equitable campus.”