Study identifies potential new drug for Parkinson’s-related cognitive decline, dementia

Parkinson’s disease causes difficulty in movement and balance, but its cognitive symptoms receive less attention and have no good treatments. A U of A College of Medicine – Tucson team hopes to change that.

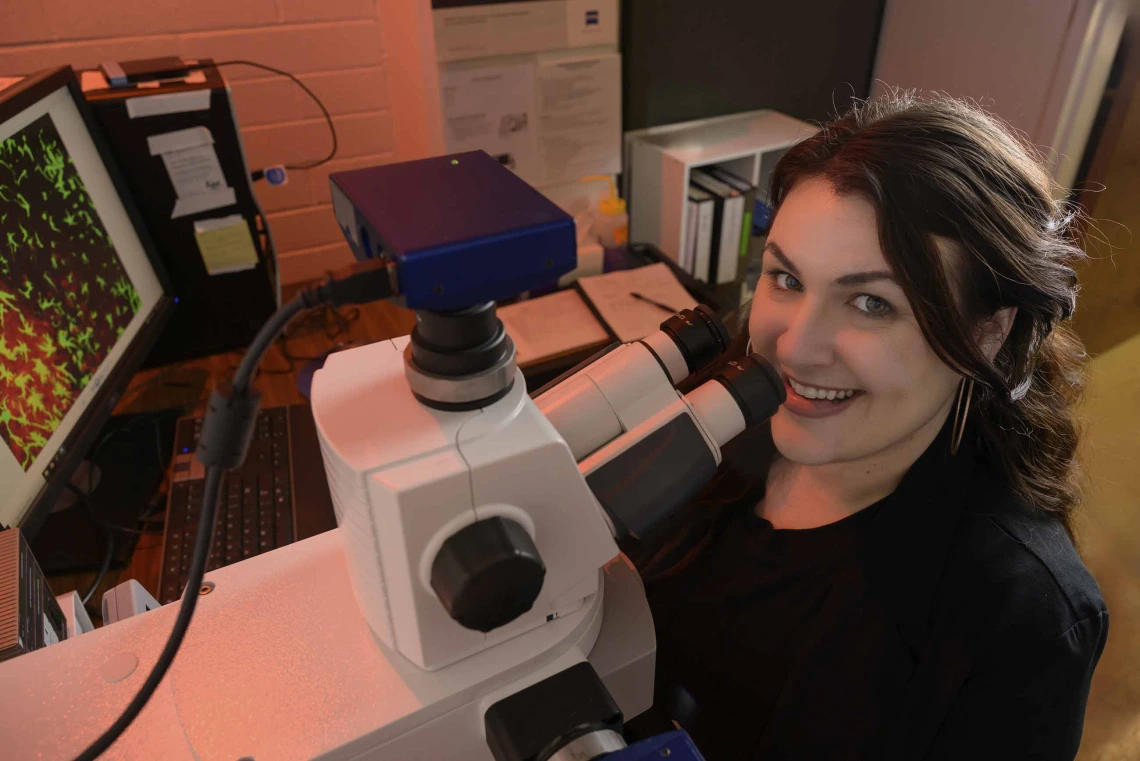

Kelsey Bernard, PhD, was the first author on a paper that showed the protein PNA5 could possibly prevent cognitive decline in people who have Parkinson’s disease and related disorders.

Photo by Kris Hanning, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications.

A recently published study by researchers at the University of Arizona Health Sciences found that a tiny protein called PNA5 appears to have a protective effect on brain cells, which could lead to treatments for the cognitive symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and related disorders.

Parkinson’s disease, a neurological disorder best known for causing tremors, stiffness, slow movement and poor balance, also causes cognitive symptoms that can progress to Parkinson’s dementia. While there are medications that control the disease’s motor symptoms, there are no effective treatments for its cognitive symptoms.

Lalitha Madhavan, MD, PhD, is an associate professor of neurology at the College of Medicine – Tucson.

Photo by Kris Hanning, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications.

“When patients are diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, 25% to 30% already have mild cognitive impairment. As the disorder progresses into its later stages, 50% to 70% of patients complain of cognitive problems,” said Lalitha Madhavan, MD, PhD, an associate professor of neurology at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson. “The sad part is we don’t have a clear way to treat cognitive decline or dementia in Parkinson’s disease.”

A research team led by Madhavan, in collaboration with Torsten Falk, PhD, a research professor of neurology, is investigating PNA5, which was developed by Meredith Hay, PhD, a professor of physiology. They recently published a paper in Experimental Neurology showing that, in an animal model, PNA5 appears to have a protective effect on brain cells.

“With PNA5, we’re targeting cognitive symptoms but, in particular, we’re trying to prevent further degeneration from occurring,” said Kelsey Bernard, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the Madhavan Lab and the study’s first author. “By going down the protective route, we can hopefully prevent cognitive decline from continuing.”

Dialing back inflammation

The causes of neurodegenerative diseases are largely mysterious, but the current thinking is that they involve inflammation, a normal function of the immune system that is usually short-lived in response to infections or wounds. If inflammation becomes chronic, however, it can do lasting damage.

Bernard said inflammation plays a significant role in Parkinson’s disease when microglia, specific immune cells in the brain, enter a supercharged state.

“Normally, microglia are looking for things like viruses or injury and secreting substances that block off the damage,” she said. “In Parkinson’s disease, when they’re constantly activated, microglia can propagate further damage to the surrounding tissue. That’s what we see in Parkinson’s brains, particularly in regions associated with cognitive decline.”

The team found that these supercharged microglia flooded their environments with an inflammatory chemical, supporting previous research linking that chemical with cognitive status.

“This inflammatory chemical can directly interact with neurons in a region of the brain important for learning and memory,” Bernard said.

Torsten Falk, PhD, is a research professor in the College of Medicine – Tucson’s Department of Neurology.

Photo courtesy of Biocommunications, U of A Health Science Office of Communications

After treatment with PNA5, researchers watched blood levels of the inflammatory chemical decrease, correlating with a reduced loss in brain cells. They said they believe PNA5 dials back the microglia’s overly active immune response and brings it closer to a normal state.

The researchers hope that by suppressing production of this inflammatory chemical, PNA5 can protect the brain.

Expanding treatment options

When developing PNA5, Hay, in collaboration with Robin Polt, PhD, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the U of A College of Science, made small tweaks to the structure of a chemical the body naturally makes, enhancing its ability to enter the brain and stay there longer. Hay is studying PNA5’s potential in treating other types of dementia, such as vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

“It has already been tried and tested in other models, and that makes me more optimistic,” said Madhavan, who, along with Polt and Hay, is a member of the BIO5 Institute.

She said she hopes the team’s investigations into PNA5 will eventually lead to a drug that people with Parkinson’s disease can take to alleviate cognitive symptoms, though they may still need to take other drugs to control motor symptoms.

“I think about it as a cog in the wheel — there are going to be other drugs that support other aspects of Parkinson’s. Taking multiple drugs is never fun, but it’s a complex condition and there can only be complex solutions,” she said. “The beauty of the brain is the interconnectedness, but it also adds to the complexity.”

The researchers said their next steps are to conduct further studies to identify biomarkers, refine dosages, investigate sex differences and figure out how PNA5 might work.

“PNA5 seems to have a possibility of stopping or delaying Parkinson’s progression to some extent and could improve the health of brain cells or prevent cells from dying,” Madhavan said.

The publication was the product of Bernard’s doctoral research, which she performed under the mentorship of co-senior authors Madhavan and Falk.

“The brain is the most interesting part of the body,” Bernard said. “These cells are fascinating — what causes them to work correctly and what causes them to go awry.”

This research was supported in part by the Michael J. Fox Foundation under award no. MJFF 024922, the National Institutes of Health under award no. T32 AG1081797, and the ARCS Foundation Scholarship.

Contact

Anna Christensen

College of Medicine – Tucson

520-626-9964, achristensen@arizona.edu