What Your Sweat Can Tell Doctors About Your Health

The collection and analysis of sweat, which contains hundreds of biomarkers, is poised to become the newest diagnostic tool in precision health care.

It’s a common occurrence: a doctor’s appointment results in a visit to the lab for testing. “Isn’t there an easier way?” you think to yourself as the technician inserts a needle into your arm and draws the blood that will give your doctor vital information about your health.

The blood contains many molecules that are measurable indicators of biological processes (such as glucose metabolism), disease processes (such as inflammation or arthritis) or responses to therapeutic interventions. For example, a common molecular biomarker is cortisol, a steroid hormone that can be used to gauge a person’s stress response.

“Blood has been the go-to source of biomarkers for over 100 years,” said Esther Sternberg, M.D., research director of the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine and founding director of the Institute on Place, Wellbeing & Performance at the University of Arizona Health Sciences. “And right now, the only way we can measure these biomarkers is with a blood draw.”

Sternberg hopes to change that through research that is happening in her Stress Challenge, Sweat Collection and Stress Correlation, or SC3 laboratory. Tucked in the basement of one of the many buildings on the University of Arizona Health Sciences campus, the SC3 lab has a unique goal: to make people sweat in the name of research.

Sweat is often viewed as nothing more than a salty liquid byproduct of perspiring, the body’s natural cooling mechanism. But each drop of sweat is a treasure trove of molecular biomarker information that scientists are just beginning to explore.

“Blood and sweat are two different compartments of the body,” Sternberg said. “When you measure a molecule in blood, it tells you what’s going on systemically, in the blood. Molecules in sweat can tell you something different than molecules in blood or they can tell you the same thing. Sweat is a great window into the health status of an individual, and with our instruments in the lab we can measure minute amounts of dozens of molecules in sweat.”

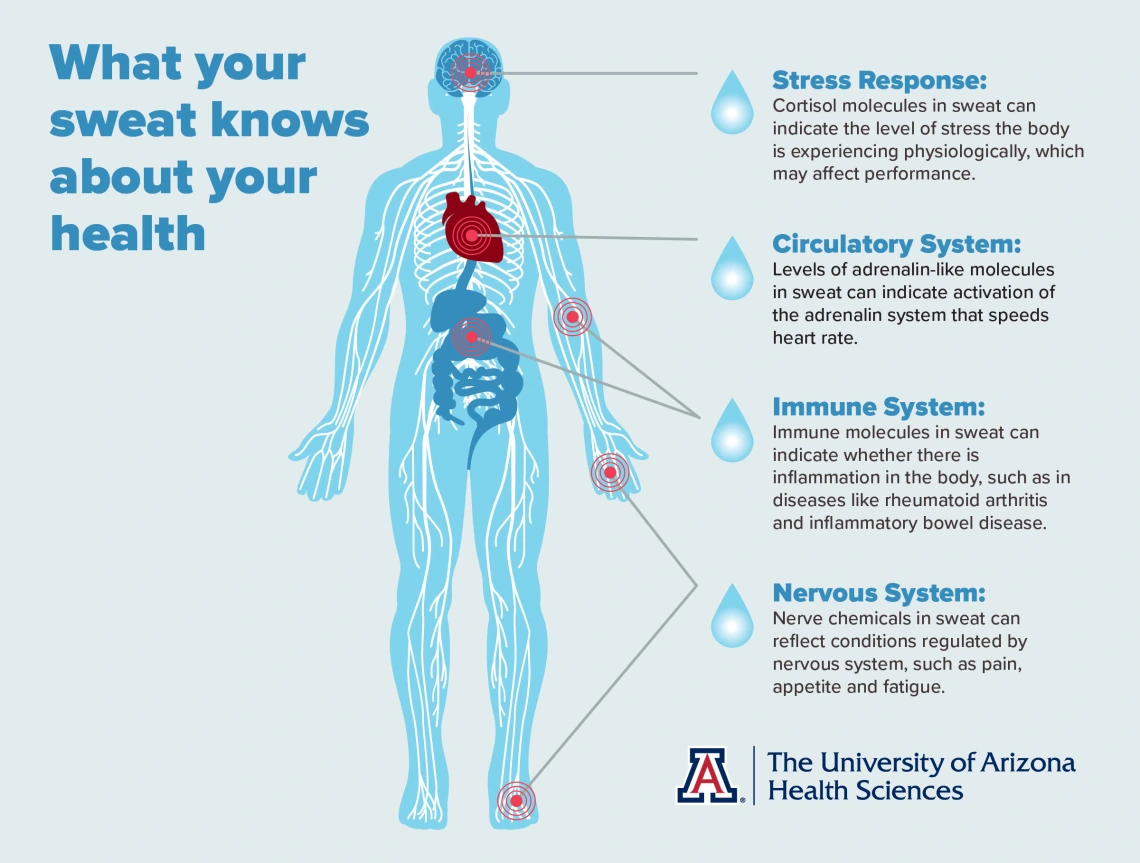

Sweat contains hundreds of biomarkers that doctors can utilize to determine the status of a person’s health. For example, immune biomarkers in sweat could be measured to determine if a person’s rheumatoid arthritis is active or quiescent, and cortisol could be measured to determine the level of a person’s stress response.

In the latter case, the ability to continually collect sweat for analysis could offer doctors a comprehensive look at how an individual’s health status changes throughout the day.

“When you draw blood, you get a picture, a snapshot, of the individual’s health status at that moment in time. You don’t get a continuous picture of how that health status is changing over time,” Sternberg said. “With sweat and with the devices we are aiming to develop, the goal is to be able to continuously measure whatever molecule we are interested in to get a continuous picture of the health status of the individual over time.”

Sweat is often viewed as nothing more than a salty liquid byproduct of perspiring, the body’s natural cooling mechanism. But each drop of sweat is a treasure trove of molecular biomarker information that scientists are just beginning to explore.

Researchers use a pump device to capture sweat from the skin. In the future, they hope to develop a “lab on a bandage” wearable to collect and analyze sweat.

To that end, Sternberg is collaborating with materials science and engineering professor Erin Ratcliff and J. Ray Runyon, a research assistant professor in the College of Agriculture and Life Science’s Department of Environmental Science, who runs Sternberg’s SC3 lab at the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine. Together they aim to develop a “lab in a bandage,” a wearable device that would measure molecules in sweat continuously and in real time.

“Our aim is to develop a device that could measure molecules of any system in the body in sweat to tell you the status of your immune system, your nervous system, your kidneys, your stress response, whatever it is you’re interested in, without having to draw blood,” Sternberg said. “In the future, instead of going to a clinic and having your blood drawn, you'll be able to wear a device that will signal your smartphone and tell your healthcare provider the exact status of whichever bodily system you're interested in, because we can measure most of these molecules in sweat.”

Extras

Contact

Stacy Pigott

Office of Communications

520-621-7239

spigott@arizona.edu