Delivering Health Care Solutions Through Device Design

A University of Arizona Health Sciences Design course teaches students to use a human-centered approach to develop new technologies to improve lives.

Like many of his peers on an educational track toward medical school, Thomas Knapp was inspired to help people. Unlike most of the future physicians around him, Knapp realized the clinical setting was not the best fit for him. He was intrigued by artificial limbs and other devices that could help people with disabilities achieve normalcy in their lives and make everyday tasks more practical.

(From left) Travis Sawyer, PhD, leads a brainstorming session with doctoral students Justina Bonaventura, Noelle Daigle and Natzem Lima for a project focused on diffusion MRI validation.

So rather than apply to medical school after earning a bachelor’s degree in physiology, Knapp pivoted his interests to biomedical engineering as a doctoral student.

“For me, it was a more interesting way to help people and improve health care in general,” Knapp said. “It’s really exciting to see what we can do now in medicine because of technology.”

Knapp never took an engineering course as an undergraduate student, but he was fascinated by what he was learning in his upper-level biomedical engineering courses. Still, he still felt like there was a missing component in the coursework.

“You learn about all these amazing devices, but they don’t teach you how to actually develop them,” Knapp said. “So you have this vision of where you want to be, but how do you get there? How do you create something that people are going to use and benefit from?”

That was when Knapp enrolled in a University of Arizona Health Sciences class called “Device Design in the Health Sciences: Developing Tools for Health Care Solutions using Design Thinking.” Led by Travis Sawyer, PhD, assistant professor in the James C. Wyant College of Optical Sciences, the Health Sciences Design course allows students to apply design thinking principles and work in interdisciplinary teams to gain hands-on experience developing devices for application in the health sciences.

“Taking the Device Design course was a ‘no-brainer’ for me,” Knapp said. “Travis’ class bridged that gap between my foundational knowledge and how to develop a solution for a problem that is going to help others.”

Focusing on human-centered design

Having the skills to design and build a new device is one thing, but it does not ensure that anyone will use or benefit from the device. That is what makes Dr. Sawyer’s Device Design course unique. Open to undergraduate and graduate students, it teaches diverse groups of students how to use design thinking to address needs in the health care system that could be solved using devices.

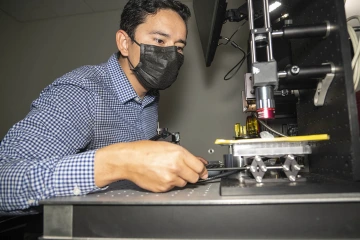

Natzem Lima performs hardware adjustments on an imaging system to measure biomarkers for esophageal cancer screening during the prototyping phase of the course.

“The concept of human-centered design is most important to me,” Dr. Sawyer said. “I think that gets lost on a lot of people, whether they are doing engineering or research. The whole point in the end is trying to improve people’s lives, and I try to emphasize that a lot throughout the course."

At the beginning of the semester, students work together to identify health care problems that need to be addressed. This portion of the semester can be the most challenging, Dr. Sawyer says.

“Most students are unfamiliar with the needs-finding part of the process,” Dr. Sawyer said. “They are coming up with needs, researching problems and engaging with health care professionals who have the need or are trying to fill a need. Once they work through that part of the process, the students get more comfortable and confident.”

Students meet twice a week, with structured, didactic learning on Tuesdays. On Thursdays, students collaborate in small teams to apply the design thinking process to their own projects.

Learning to empathize with people

The projects students choose can be a new research topic or one they are already working on in a research lab. Last fall, all of the students were advancing their own research projects, but that isn’t always the case.

"By the end, whether or not the students are carrying their projects forward through their own research, the best outcome I can hope for is that each of them has stronger belief in themselves as innovators to be able to make an impact in the health care system,” Dr. Sawyer said.

As part of the prototyping and testing stage, Noelle Daigle peers through a fluorescent microscope to inspect a tumor sample.

When Knapp took Dr. Sawyer’s class in Spring 2022, his team developed a project around improving communication for patients who undergo dental procedures. The idea was initiated by one of the students, who had first-hand experience with the struggle of communicating while getting a root canal.

“Even though it was one of our own experiences, it represented the first phase of the design thinking process,” Knapp said. “The first part is about empathizing with people around you, looking into your community and seeing what actual problems are out there.”

Knapp said his team was driven by the desire to reduce fear and overcome anxiety for patients during a dental procedure.

“We thought that if there was a way for the patient to actually communicate thoroughly to the dentist during the procedure, then they might get some peace of mind – even basic things like ‘I need suction,’ ‘I’m choking,’ or ‘this hurts a lot, can I please have more anesthetic?’” Knapp said. “That ability to communicate can make the experience a lot more reassuring for the patient.”

Finding meaning, value and novel ideas

Knapps’ team chose the dental communication project, in part, because of their enthusiasm for prototyping a design for their device idea. But because of the constraints of fitting the course into one semester, they did not get to see their device through to completion.

Thomas Knapp’s (center) transition away from clinical health care toward health care device design included taking a Health Sciences Design course led by Kaci Kielbaugh, PhD, (left), director of the Health Sciences Design program. Bridget Slomka (right) also took the Design courses led by Drs. Kiehlbaugh and Sawyer and is now a HealthTech fellow at Harvard Medical School.

“Seeing the end protype is the most exciting thing,” Dr. Sawyer said, “but I'd say it's the least important part. The course is really about the process and understanding the need, defining it and then concept generation. As our Health Sciences Design program builds, we could be in a position to add a second semester that would allow the students to push their projects further through the prototyping phase.”

Even though the dental communication device didn’t come to life, looking back, Knapp realizes the value of what he learned in the Device Design course. Those lessons will ultimately enable Knapp to see real-world projects come to fruition as he continues his doctoral research in optical imaging under the advisership of Dr. Sawyer.

“My research focus is the development of novel imaging instruments for cancer detection and treatment,” Knapp said. “Eventually, I think my ideal situation is that I would be developing imaging instruments for robotic surgery because I feel like that is such a cool and useful way of treating patients.”

Knapp’s future goals mirror what Dr. Sawyer hopes all students gain from his class.

“I really hope the course helps students understand that what they did, and hopefully what they will do in the future, have meaning and value for improving patient's lives and the healthcare process.”

Our Experts

Contact

Blair Willis

Health Sciences Office of Communications

520-419-2979

bmw23@arizona.edu