Colleges Provide Tools to Help Students Avoid Career Burnout

The five Health Sciences colleges are preparing medical, nursing, pharmacy and public health students to manage stress, survive and thrive as they enter the workforce.

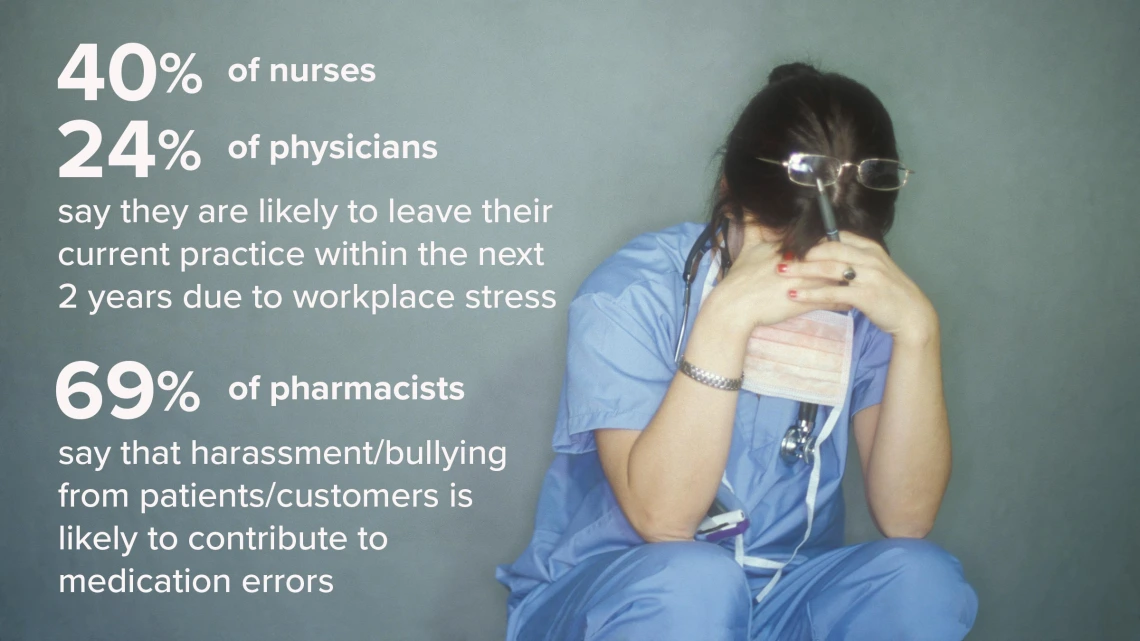

The Great Resignation of 2021 is creating a labor crunch in health care that studies indicate will get worse before it gets better, with one in five workers quitting their job since February 2020 due to burnout and more looking to leave. (Photo Illustration by Paul Fini. Sources: HealthEvolution.com, Mayo Clinic Proceedings and 2022 APhA/NASPA National State-Based Pharmacy Workplace Survey – Initial Findings)

As the COVID-19 pandemic taxed health resources in Arizona and across the country, health care was the second largest sector hit by the “Great Resignation.”

A recent American Medical Association study forecast the situation would only get worse. It calculated 1 in 5 physicians and 2 in 5 nurses would leave their practices within two years due to workloads, stress, anxiety and depression from the pandemic. All health care professionals said they plan to cut work hours in the short term.

Tragically, some health care workers overwhelmed by pandemic stress took their own lives, which led to the signing in March of the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act to better promote behavioral health and well-being services for front line health workers.

Building resiliency

The overall job sector loss and future workforce implications have health care organizations and the colleges and universities that train health care professionals ramping up efforts to address issues many say existed before the pandemic, which only exacerbated longstanding problems.

That includes the University of Arizona Health Sciences.

All five UArizona Health Sciences colleges are working to address burnout by adding more emphasis in their programs and curricula to address mental health and resiliency.

College of Nursing

Jessica Rainbow, PhD, RN, a UArizona College of Nursing assistant professor, coauthored an article with two former students, “Nurses don’t want to be hailed as ‘heroes’ during a pandemic – they want more resources and support,” for The Conversation last fall.

Jessica Rainbow, PhD, RN, UArizona College of Nursing assistant professor

She noted 1,150 nurses, the highest figure for all U.S. health workers killed by COVID-19 through March 2021, had died in the pandemic. Overall, about 3,600 U.S. health workers – 54 from Arizona – had died by that time. Today, over 4,100 deaths and 1.07 million health care personnel infections in the U.S. due to COVID-19 have been reported.

Dr. Rainbow wrote about COVID’s impact on nursing as one of several Health Sciences nurses studying well-being during the pandemic. In one study, she monitored voicemails health care workers shared about experiences. She warned of exasperated nurses leaving the field due to burnout from overwork and limited staffing, resources and safety precautions they felt put lives at risk in the pandemic.

“We know burnout is 80% your employer and your work situation, and 20% you being a resilient person. Sometimes as a teacher I worry about us telling students, ‘Oh, we’re going to build resilience in you.’ Those are great programs, but as much as we can instill resiliency, if we’re sending them into toxic work environments, that’s such an important piece of this, too,” she said.

For positive workplaces and resilient teams, Dr. Rainbow also is involved in a National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health work stress study to survey and explore approaches to improve workforce situations from home health aides to hospital staff.

Cheryl Lacasse, PhD, RN, AOCNS, professor, coordinator of the RN-MSN Program and director of Teaching/Learning Practice and Evaluation at the UArizona College of Nursing

“There's so much in this pandemic you can't fix. But those feedback loops are really helpful,” Dr. Rainbow said, particularly when something gets corrected. “Organizations now feel like they have to address burnout, or at least make an effort, which I think is really good, too. That kind of culture shift is really positive.”

Cheryl Lacasse, PhD, RN, AOCNS, the college’s director for Teaching/Learning Practice and Evaluation, agreed.

“The group of students we have now are very aware what the landscape looks like in health care. Some are a bit apprehensive about what they're walking into but very excited to begin in the nursing profession. I think it's incumbent on us as experienced nurses and educators to give them those tools to manage high levels of stress in this environment,” she said.

Colleges of Medicine

Physician burnout was considered critical before the pandemic, said Violet Siwik, MD, the UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson’s assistant dean for student affairs, but successive waves of COVID-19 patients who threatened to overwhelm hospitals made it more of a crisis.

Violet Siwik, MD (center), UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson assistant dean for student affairs and assistant professor of family medicine, flanked by first-year medical students Caitlyn Dagenet and Meghana Bandlamuri, who were added recently to the college’s Wellness Committee

Younger physicians are generally more open to counseling and therapy, Dr. Siwik said. Increasingly, they’re provided more tools through medical school to cope, too.

In its curriculum, the college’s doctor-patient training occurs largely via its Societies Program, with students sorted into four houses under a house dean, physician mentors and specialty advisors. The team structure offers support on multiple levels, including peer-to-peer. Among complementary services are Early Alert digital check-ins for students on mood, sleep, etc., and My MD-to-Be notices for family and significant others, so they’re aware of study workloads and can give emotional support.

That’s not to mention the Healer’s Art elective that many first- and second-year students take each year. Since physicians inevitably lose some patients, the class delves deeper into grief, loss, stress and self-care.

Several faculty volunteer to teach the course. “The goal is to share our stories, our losses, talk about what's helpful when someone is experiencing a loss, what's not helpful,” Dr. Siwik said.

College of Medicine students gather March 3 for Pet Park Day at Tucson’s Himmel Park to share a little casual pet therapy time.

“With a lot of classes still online, we don't have as much in-person interaction with our whole class, so we're trying to do events to get more people together,” Dagenet said. “With the dog social event at the park last month, we highly encouraged everyone to attend, especially if you didn't have a pet, to get that casual pet therapy.” They’ve also hosted yoga and cooking events via Zoom.

Bandlamuri said they are hosting their first Academic Wellness Collaborative, an ongoing quarterly meeting hosted with Banner Health, the College of Medicine – Phoenix and the College of Medicine – Tucson for residents, fellows and students to share views on well-being issues. Related physician wellness, including for faculty, is managed via the Cultivating Happiness in Medicine Program.

College of Pharmacy

Nancy Alvarez, PharmD, associate dean for the R. Ken Coit College of Pharmacy’s Phoenix campus and editor/author of the book “Bypass Pharmacy Burnout,” said pharmacist burnout – already a problem before the pandemic – has only increased.

Nancy Alvarez, PharmD, associate dean, academic and professional affairs, R. Ken Coit College of Pharmacy, and author/editor of “Bypass Pharmacy Burnout”

Dr. Alvarez said this includes advising against unproven or even dangerous “therapies,” for which pharmacists were harassed by customers. She said an exodus of pharmacy staff continues.

“I’m thankful I haven’t experienced that kind of abuse, but I’ve definitely heard about it,” said Phoenix campus pharmacy student Eric Taylor, who graduates this spring. “It’s not just community pharmacies. It can be in the hospital. It could be anywhere you work. And it’s disheartening. I’m hoping it wouldn’t be to the point where I would consider leaving the profession. It’s really a shame.”

A recent news report found 78% of pharmacists are exhausted from work, made worse by the fact 70% of independent pharmacies struggle to fill pharmacy technician jobs, which only adds to workloads. Many also continue to feel underappreciated for their vital role in health care, Dr. Alvarez said.

“The pandemic amplified problems already there, not only in community practices like pharmacy chains, grocery- and other retail-affiliated and independent pharmacies, but in health systems and, quite frankly, academia as well,” she said. “Chronic stressors people experience can lead to cynicism and depersonalization. That then leads to burnout.”

Drew Koch, MEd, whose College of Pharmacy work involves student retention, analytics and student development, co-facilitates a course, Leadership in Pharmacy, with several modules that allow students to explore how they react to stress.

As a further remedy, the college’s wellness committee tries to institute at least one new activity a semester to break the tension. Faculty, staff and students also are sent a weekly email on wellness tips and a wellness newsletter three times a year, Koch said.

The hope is that instilling habits and mindsets will enable students to more easily navigate the PharmD program and, when they’re in the profession and feeling overwhelmed, better manage stress, he added.

College of Public Health

During the extended stay-at-home lockdown period, the college surveyed faculty, staff and students to assess their needs, said Andre Dickerson, assistant dean of student services and alumni affairs at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health.

Andre Dickerson, assistant dean, student services and alumni affairs, Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health

What was found, he said, reflected the stress that Health Sciences public health workers saw in their outreach across Arizona. This included financial, food, housing and health insecurity, Dickerson said. Many also struggled with technology deficiencies at home compared to the office or classroom, which impaired their work and study capabilities.

Through the UArizona COVID-19 Response Task Force, the college’s faculty worked to develop ways to address those needs across the broader campus, he added. They also integrated resolutions into advice for public policy consideration across the state as well as into public health course work.

“That's where the curriculum itself continues to adapt its relevancy and applicability to what's happening in the real world,” Dickerson said. “These students need skillsets to go out and be public health practitioners. They’re assessing how needs are changing, including health disparities for a specific population that are now intensified as a result of COVID. The college as a whole continues to assess students’ basic needs and modify our approach to services accordingly.”