Fast Work: Creating an Antibody Testing Program from Scratch

Health Sciences researchers and staff worked quickly to operationalize testing for all of Arizona’s first responders and health-care workers

Emely Mancia-Chavez, clinical research coordinator for the All of Us research program, performed a blood draw for a COVID-19 antibody test during the pilot phase of the program in Pima County.

The University of Arizona Health Sciences developed the antibody test that is now being used to find out how many of the state’s 250,000 health care workers and first responders have been exposed to the virus that causes COVID-19, but the route to the statewide testing involved a big change of plans and a quick ramp-up of logistics.

Building on the work of Health Sciences researchers, the university’s antibody testing initiative was originally conceived as a tool to potentially help navigate campus reentry. But a partnership forged with the state quickly turned the test into a large-scale public health tool, requiring a significant change in how resources and staff are usually deployed at the university.

Alexandria Chaput, a research specialist at the College of Medicine – Tucson, checks Jacob Smith in for his appointment to receive the COVID-19 antibody test in early May.

As the scope of the project expanded to more than 30 sites across the state, the timeline accelerated dramatically. The initial wave of 250,000 antibody tests, funded by $3.5 million from the state, prioritized Arizona’s health care workers and first responders and was slated to start in May.

For Lauren Zajac, MPA, assistant vice president of Health Sciences Research Administration, that meant expediting a host of legal and compliance reviews and approvals, not only with the research scientists and the university, but also with each associated site where testing would take place.

Together with the Health Sciences research administration team, Zajac acted as the project’s operational “broker,” and worked with the researchers to develop institutional review board documents and finalize the contract with the state.

“Antibody testing really became a call to arms,” Zajac said, “and a lot of people were really motivated to jump in and help.”

Collaboration with All of Us

When it came time to design and operationalize a scalable testing workflow, Zajac knew she had a strong partner in All of Us research program Director Jennifer Craig-Muller.

Craig-Muller oversees 100 phlebotomists and clinical research coordinators at 14 sites as part of All of Us, a National Institutes of Health-funded initiative to advance precision medicine.

Stephanie Morales, an All of Us research program clinical research coordinator, draws blood from Emily Jean Krull for a COVID-19 antibody test.

Craig-Muller tapped a phlebotomy expert on her team to create the blood collection operations, and a technology expert designed the online platform to register participants and track the testing process.

Across working groups, more than 200 people—from University of Arizona facilities management and information technology departments to research and supply chain coordinators—participated in a dry run the day before testing started.

The practical experience of the All of Us team members helped the five-site, 4,500-person pilot program in Pima County run smoothly.

“It was a big moment seeing the commitment of our team, coming forward during this time and helping out,” Craig-Muller said.

The first day of testing ended up going so well, Craig-Muller said, “that halfway through, people were asking ‘When will it get busy?’ But the scheduling and flow was working, and eventually we were even able to increase the number of tests administered.”

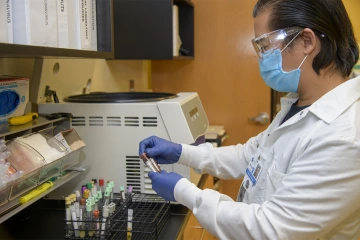

Phlebotomist and lab manager Bruce Cimafranca prepares to centrifuge blood specimens at a Winslow, Ariz, medical center. The specimens are then packaged and couriered back to the lab in Tucson for testing.

The pilot team tested 5,880 first responders, health care workers and members of the general public, surpassing the initial goal of 4,500.

Behind the scenes, a small university army was working overtime, reaching out to local vendors and clinical labs to keep the sites stocked with supplies, including needles, tubes and personal protective equipment.

“Having enough supplies was definitely the biggest challenge. There were two to three people actively seeking out supplies for us every day,” Craig-Muller said, adding that a UArizona researcher used their lab to make hand sanitizer specifically for the sites. “This was truly a team effort.”

Melissa Colchado, chief of staff for management and policy at UArizona Health Sciences, worked across the information technology, supply logistics, administration and clinical groups to ensure effective collaboration as the testing progressed statewide.

“People really cared about being part of this process,” Colchado said. “I would contact groups I had never worked with before, and the next day they would be ready to do whatever I requested. People wanted to be a part of the solution.”

Expanding Throughout Arizona

Building on the success of the Pima County pilot program, testing quickly expanded to the Phoenix area. In the state’s rural areas, Daniel Derksen, MD, a professor in the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health and Health Sciences associate vice president for health equity, outreach and interprofessional activities, was able to leverage existing relationships with critical access hospitals and health centers across 13 counties to find partner facilities to serve as testing sites.

“It was important to balance the number of tests done in urban and more rural areas, and to reflect the state’s diversity with a focus on those providing the care and responding to emergency needs during this pandemic,” said Dr. Derksen, who is director of the Center for Rural Health. “We've been working with and providing resources to folks in these rural areas for many years. They are our natural allies and partners for this testing initiative, which benefits their communities.”

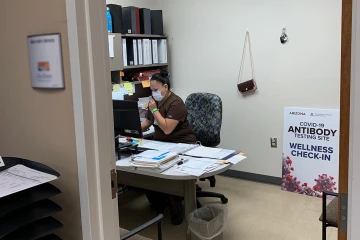

Jewels Parker, lab supervisor at a health care center outside of Phoenix, in her office with antibody testing signage delivered by Dan Derksen, MD.

Other required supplies, including collection tubes and personal protective equipment, were shipped directly to each site. Health Sciences project manager Randi Willmeng served as a point of contact for the sites, coordinating services and providing additional information.

The day trips to the sites also helped Dr. Derksen consider appropriate routes for a courier service, which picked up the specimens from each site every day and transported them back to the lab in Tucson for testing.

“I think people felt honored to be part of something like this,” Dr. Derksen said. “In addition to providing a valuable public health service, this process has touched thousands of people in the planning and implementation. And I think that is extraordinary.”