Phoenix’s Yamoah and Chiamvimonvat make a great team

Married researchers know how to collaborate when it comes to life, work and winemaking.

In addition to partnering at work at the U of A College of Medicine – Phoenix, married researchers Ebenezer N. Yamoah, PhD, and Nipavan Chiamvimonvat, MD, are a team when it comes to winemaking and pressing olive oil.

Photo courtesy of Ebenezer N. Yamoah

When Megan A. Yamoah was 9, she gave her parents an ultimatum: Quit talking about work.

She meant it.

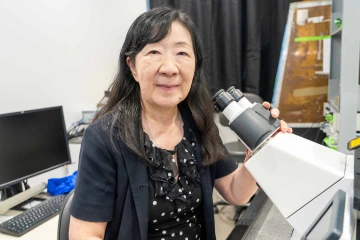

Nipavan Chiamvimonvat, MD, and her husband Ebenezer N. Yamoah, PhD, joined the U of A College of Medicine – Phoenix almost a year ago. They’re partners through and through, carpooling to campus and editing each other’s grant submissions.

Photo by U of A College of Medicine – Phoenix

“If I ever hear anything about spiral ganglion neurons again, I will never have dinner with any of you,” Megan testily told her parents. So recalled Ebenezer N. Yamoah, PhD, a professor in the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix Department of Translational Neurosciences who was guilty of bringing up those pesky neurons.

The young Yamoah won.

“We had dinner with her until she went to college,” Yamoah said of his only child, who is working toward a doctorate in economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

With Megan out of the house, work is back on the table, which is good because Yamoah and his wife of 28 years, Nipavan Chiamvimonvat, MD, chair of the Department of Basic Medical Sciences at the U of A College of Medicine – Phoenix, have a lot to talk about when it comes to the jobs they love.

“If they told me tomorrow would be the end of the world, I would be in my lab, breaking protocol, sipping a glass of wine. That would be enough,” said Yamoah. “You have to enjoy what you are doing, and we enjoy what we are doing. It can be stressful. You have to compete and sometimes you don’t hear what you expect to hear, and you have to struggle. But at the end of the day, we enjoy what we’re doing, and it’s fun.”

Like clockwork

Yamoah and Chiamvimonvat leave their house at 7:30 a.m. sharp and come home at 7:30 p.m. on the dot.

“Our neighbors said they don’t need to have a clock,” laughed Chiamvimonvat.

If it’s not obvious already, you don’t have to be around them long before realizing the couple practices what they preach: That you must approach life and work with a healthy sense of humor.

The two joined the College of Medicine – Phoenix last July. Chiamvimonvat, a physician-scientist, oversees the department that teaches beginning medical students the fundamentals. Her research focuses on understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms contributing to cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in heart failure.

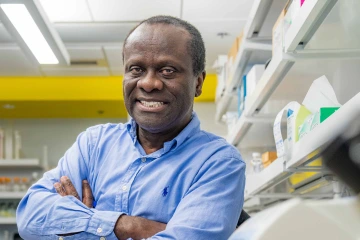

Ebenezer N. Yamoah, PhD, says he pays attention to the big picture while his wife is very detail-oriented. They balance each other to make a great team.

Photo by U of A College of Medicine – Phoenix

Yamoah studies the biological mechanisms of hearing and age-related hearing loss. His work toward understanding the genetic and cellular mechanisms of hearing loss is key to discovering ways to recover age-related hearing loss, which, according to the National Institutes of Health, is the most prevalent chronic sensory deficit experienced by older adults.

It doesn’t seem the two fields have much in common, yet the couple have coauthored more than a dozen papers. The inner ear and heart rely on distinct proteins for their specific functions and there is some overlap. For example, Chiamvimonvat said, a rare genetic condition called Jervell and Lange-Nielsen Syndrome causes profound hearing loss as well as a disruption of the heart’s regular rhythm from a mutation of the same protein.

“Even though the systems of the heart and hearing seem very separate, fundamentally the cells rely on their ability to fire, or become excitable,” she said.

It can be tricky being a couple in the same field, but the two have made it work as they’ve hopscotched from coast to coast. Yamoah even commuted two hours and 15 minutes — one way — from Davis, California, where Chiamvimonvat held multiple appointments at the University of California, Davis, to the University of Nevada, Reno, where he worked.

The advantages far outweigh the negatives, Chiamvimonvat said.

Ebenezer N. Yamoah, PhD, and Nipavan Chiamvimonvat, MD, own 30 acres in Sonoma where they grow grapes and olives.

Photo courtesy of Ebenezer N. Yamoah

“We speak the same language,” she said. “We say ‘NIH grant,’ and we both understand what effort it takes and how hard you have to work. If I have a grant deadline and I have to work around the clock, then Ebenezer will understand because he may need to do the same thing.”

The duo is in sync in other ways, too. Though they score almost exactly the same on personality tests, they have their differences, which they love to tease each other about. Yamoah said he focuses on the big picture while his wife is detail-oriented. When they look over each other’s grants, Yamoah said he doesn’t recognize them after his wife’s edits.

“I have to reorganize everything,” Chiamvimonvat explained.

“She thinks I’m the most disorganized human being,” Yamoah said. “She thinks my tombstone should read, ‘If only he were organized, he would have been a great man. But he wasn’t.’”

Luckily, Yamoah said, they don’t work next to each other in the Biomedical Sciences Partnership Building.

“The good thing is that she is on the eighth floor, so before she comes to the fourth floor and we go home, I try to make sure the office is clean,” he joked.

A perfect match

Yamoah, the youngest of four, was born and raised in Ghana. He left home as a teenager to study in Canada. It was at the University of Calgary where he met his future wife, one of four kids who’d also left her hometown of Bangkok, Thailand, for her studies.

The two met in a lab when Yamoah spotted Chiamvimonvat struggling with an air table, a special piece of equipment that uses nitrogen to provide a stable, vibration-free environment for experiments. It’s also quite big — some models weigh well over 400 pounds.

“I went under the table and she did not hit the table to kill me, so I knew that I had a chance,” Yamoah said.

Decades later, the two still disagree whether or not he truly repaired the table.

“She claims I cannot fix anything,” Yamoah said.

To wit, Chiamvimonvat reminded him of the time he struggled with a broken door handle and another time when they had to call a repairman to deal with a busted garbage disposal. The repairman apologized for having to charge them $120 … to press the reset button.

Yamoah may not be handy around the house, but at least he knows what he’s doing in the vineyard.

Grants and grapes

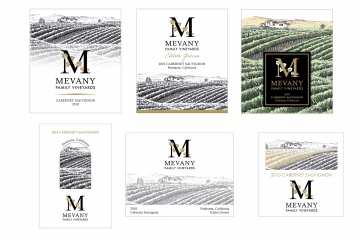

The name “Mevany” is made up from the letters of everyone in the family’s names – Megan, Nipavan and Yamoah.

Photo courtesy of Nipavan Chiamvimonvat

Not only are Chiamvimonvat and Yamoah partners at work and home, but also in winemaking.

They have 30 acres in Sonoma where they grow grapes — for pinot noir, at the moment — and olives to press into gallons of oil. In 2008, wine from Mevany (the letters from Megan, Nipavan and Yamoah) Family Vineyards won best in show at the California State Fair Home Wine Competition. These days, most of the fruit is sold to other wineries. They’ve donated their wine for fundraisers, but don’t expect to buy it anywhere. Charming as they are, Chiamvimonvat and Yamoah insist they’re no good at sales.

“We have to keep our day jobs,” Yamoah quipped.

A former colleague introduced Yamoah to viticulture and the late Henry Spoto Jr., an award-winning winemaker who was featured in Wine Spectator. After spending a year learning from Spoto, along with a few supplemental enology classes at UC Davis, Yamoah proved he was much better with a cask than a kitchen sink.

When it comes to making wine, it helps to understand some basic chemistry principles, but there are still so many variables, like weather and soil, beyond a winemaker’s control.

“You can use the same method, everything the same between Year 1 and Year 2, yet the wines would taste slightly different. So, it tells you there is something else, there’s some complexity in the process that we still are unable to understand,” Yamoah said.

Chiamvimonvat nodded and added, “Just like science.”