Fariba Donovan works to keep “The Last of Us” in fictional realm

Valley fever center mycology researcher is on the front line in the fight for her patients and to bring increased attention to the disease.

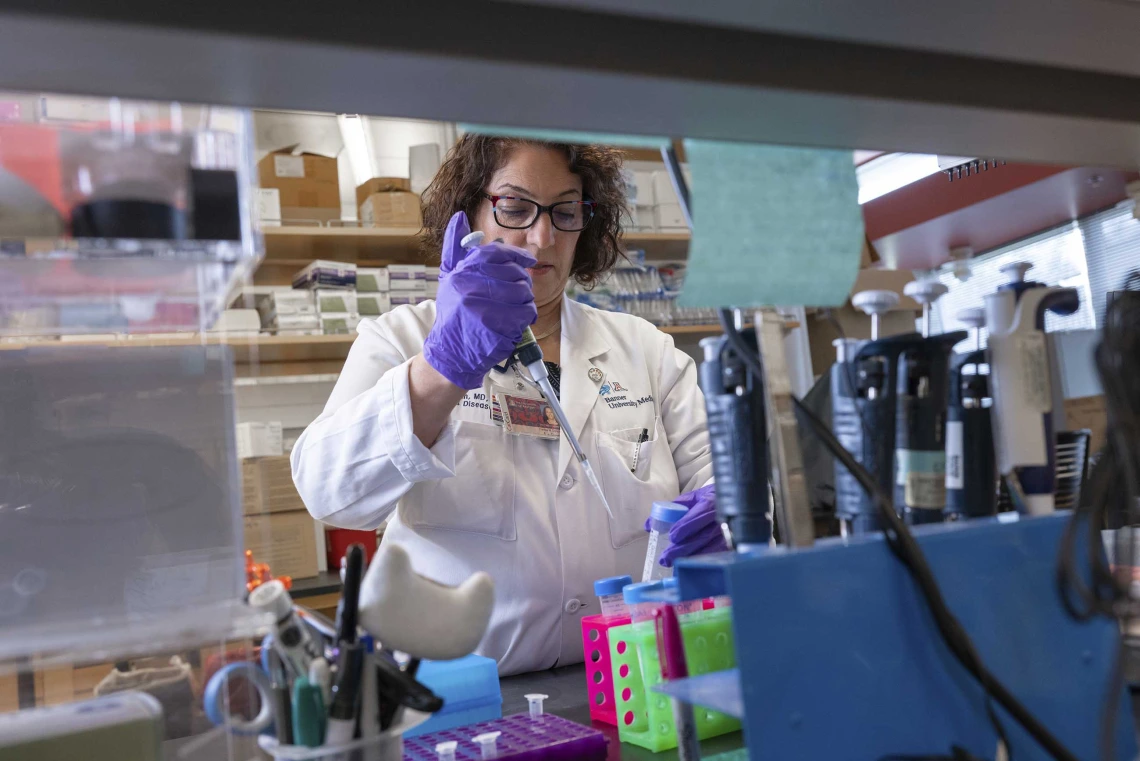

Fariba Donovan, MD, PhD, originally studied dermatology but ended up as an infectious disease specialist, devoting years to researching and treating Valley fever.

Photo by Noelle Haro-Gomez, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

See if this sounds familiar: A deadly fungus threatens humanity.

It sure does to Fariba Donovan, MD, PhD — and not just because it’s the plot of the popular HBO postapocalyptic series “The Last of Us.”

Donovan, a researcher at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson Valley Fever Center for Excellence, has never watched the show. But then, she doesn’t need to. She lives the real-life version — minus the zombies — battling Valley fever, a fungal disease that at its best barely affects its host but at its worst can be debilitating or deadly.

Since “The Last of Us” debuted in 2023, it’s drawn more attention to the respiratory disease that Donovan has dedicated years to researching and treating. There’s so much attention that Donovan — who’s not a big TV watcher, preferring to hike or play tennis instead — jokes about launching a spinoff.

“I’m thinking we should talk to the producers,” said Donovan, an associate professor in the Department of Medicine.

She certainly has a compelling story to tell.

Danger in the desert

Coccidioidomycosis, or Valley fever, is not a disease that turns heads, except when a new season of the fictional series drops. It’s considered an “orphan disease,” Donovan said, often dismissed in the United States as a local, geographic problem endemic to the desert areas of Arizona and California. But as the population increases in the desert southwest and the planet heats up, creating more hot, dry areas where the fungus can flourish, the disease will likely spread. Valley fever has already been found as far north as Washington state.

Valley fever has been around for a long time, yet health care workers like Fariba Donovan, MD, PhD, are still working to bring attention to the disease.

Photo by Noelle Haro-Gomez, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

Vally fever is caused by the Coccidioides fungus that grows in soil during the rainy season. When the earth dries out, people get sick from breathing spores that are swept into the air by wind, soil disturbance or construction, even during everyday activities like gardening. The disease is not contagious. Most infected people have mild or no symptoms, which include fatigue, fever, a persistent dry cough, and head and muscle aches. But Valley fever can spread from the lungs to other parts of the body, such as the bones, joints or brain, and become serious, even causing death.

Valley fever affects animals, too. The U of A Valley Fever Center for Excellence, founded by John Galgiani, MD, in 1996, created a vaccine for dogs, which is under review by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Center for Veterinary Biologics. It could form the basis for a possible vaccine for humans. It’s an exciting prospect since fighting the disease feels like an uphill battle, said Donovan, who’s also a member of the BIO5 Institute and graduate faculty member.

Better, more sensitive tests are needed to detect Valley fever in humans earlier in the disease, along with more treatment options, she said. Both of which she’s working on now. Donovan is president-elect of the Coccidioidomycosis Study Group, which has been around for 69 years. Yet the organization is still working to raise basic awareness — not just with the general public but with those in health care, too.

“Believe it or not, out of 1,000 new medical licenses that are issued in Arizona every year, about 40% of those people have not heard about Valley fever,” she said. “They don’t know how to diagnose or treat the disease.”

In 2022, a total of 17,612 cases of Valley fever across the country were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is likely dramatically underreported since not all states are required to report it and many cases go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. That’s troubling to physicians since the longer it takes to treat Valley fever, the worse it can be for the patient.

A 2019 study showed it took more than a month, on average, to nail down a Valley fever diagnosis, Donovan said.

“I’m talking about patients with meningitis,” she said. “You can imagine how much comorbidity and complications can be related with the delay in diagnosis. A patient has a headache, and it’s thought to be a migraine or sinusitis, or other causes until someone thinks about Valley fever. As this disease is not being treated promptly, the complications happen.”

Donovan, who splits her time between research and patient care, said a new nurse practitioner recently hired at Banner Health’s Valley Fever Center at Banner – University Medical Center Tucson is seeing patients at the Valley fever clinic five days a week, dramatically reducing wait times.

“A couple of weeks ago one of my nurses said I was booked solid until August,” Donovan said. “We want to make waiting time shorter so people can be seen and treated properly sooner.”

Finding her passion

Donovan, the youngest of three children, was born and raised in Iran. She attended medical school in Iran at a sister school to Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, learning medicine in English. When she graduated, tensions from the Iran-Iraq War made it nearly impossible to come to the United States, she said. Instead, Donovan received a scholarship to Gifu University School of Medicine in Japan. She studied dermatology, which is how she was introduced to mycology, the study of fungi.

She was presenting her research dissertation on Candida albicans — a fungus that’s normally in and on your body and can cause an infection in specific circumstances — at a conference and caught the attention of Garry T. Cole, PhD. The internationally known microbiologist and expert in Valley fever who invited Donovan to do her postdoctoral work in his lab at the University of Toledo. While practicing as an infectious disease physician one of her patients with meningitis turned out to have Valley fever, so she contacted Galgiani to discuss treatment options. A few years later, Donovan had her dream job at the U of A, combining research with patient care and mentoring students who shadow her in the hospital or clinic.

“They learn how important it is to actually connect the clinical science with basic science,” Donovan said.

Making a difference

Valley fever has no cure. Much is still unknown about the disease, and Donovan is continuously looking for answers to questions like why certain ethnicities are at higher risk and what can be done for patients with autoimmune diseases who might be at higher risk for Valley fever when receiving medications that suppress their immune systems. She said a novel antifungal medication that shows promise in better controlling the disease in severe cases is being tested.

Valley fever affects animals, too, and a vaccine for dogs that is under review could be the basis for a human vaccine.

Photo by Noelle Haro-Gomez, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

“It’s not FDA approved yet, but hopefully soon will be,” she said.

Each season of “The Last of Us” has brought media requests to the Valley Fever Center for Excellence and fresh attention while Donovan and her fellow researchers continue their quest to learn as much about the disease as they can. Recent papers have explored differences between those with central nervous system versus non-central nervous system disseminated Valley fever and ways to manage more serious forms of coccidioidomycosis.

A bright spot, though, is the constant outpouring of support from patients and their families.

“They have been amazingly supportive,” Donovan said. “If somebody had a dog who died of Valley fever, they donate their leftover medication for other dog owners to use. Their ongoing support has helped us immensely to move forward with our Valley fever research.”

It’s this and the success stories that fuel Donovan. She recalled one patient, visiting Arizona for a job interview, who went back to his home state and started suffering from migraines. He came back to start his job, still plagued by migraines, and finally learned he had Valley fever meningitis. He’s doing well with treatment. Another patient who was debilitated from an abscess on his spine is also showing improvement after being treated with the novel antifungal medication, Donovan reported. He’s back to work and goes to the gym and can drive again.

Another patient’s spouse greeted her with a hug during an office visit.

“She said, ‘Because of you, I still have my husband.’ This can be a fatal disease. So as a physician, and as a scientist, what is a better reward than that?” Donovan said. “You truly change somebody’s life. That’s the reason I’m passionate about this disease. We hope to do all we can to help our patients. It’s not easy but we continue to move forward to identify better methods of diagnosis and better treatments for Valley fever.”