For researcher, fight against cancer is personal

Facing the disease himself and in his brothers led Curtis Thorne to search for a cure.

Though cancer has had a profound and prominent role in his life, Curtis Thorne, PhD, an associate professor in the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson’s Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine and a member of the U of A Cancer Center, initially resisted being a cancer researcher.

Photo by Noelle Haro-Gomez, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

For years, cancer called Curtis Thorne, PhD, but he didn’t answer.

Not when his oldest brother, who was medically fragile, was diagnosed with a spinal cord tumor.

All three Thorne boys – Mitchell (left), Travis (middle) and Curtis (right) – fought cancer.

Photo courtesy of Curtis Thorne

Not when his middle brother died of acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Not even when he didn’t get into his choice of graduate schools to study botany, instead landing a job in a breast cancer lab.

But in the middle of his postdoctoral fellowship, Thorne – the father of a 3-year-old and a 1-year-old at the time – was diagnosed with testicular cancer.

He finally answered the call.

“I had a brother who died, another brother who was diagnosed with cancer, cancer had just been a part of my life, I thought I shouldn’t ignore this weird pull,” said Thorne, an associate professor in the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson’s Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine and a member of the U of A Cancer Center. “It’s just random luck. I don’t know that I’d call it bad luck. I feel like the best thing that happened to me was getting cancer.”

Thorne knows this sounds crazy. Hear him out.

“The calling to do cancer research had been coming at me strong most of my life, and I had been running the other way,” said Thorne, who dealt with so much medical trauma he couldn’t imagine devoting his life to the disease. “And at that moment, I just sort of relented. OK, I can do cancer research. Maybe this is my path, and I need to just accept it.”

Focusing on the fight

The Thorne Lab’s symbol looks like a pointed T, which it is. It might remind you of the Texas Longhorns logo, which it should. Thorne spent much of his life in the Lone Star State and jokingly calls himself the “cancer cowboy.” The T also gives off caduceus vibes, which seems appropriate since the lab is focused on studying and developing therapies for colorectal cancer.

Curtis Thorne (center in the plaid shirt) holds his daughter Matilda. His lab has a tradition of taking team photos at Tucson-area murals. In this 2019 photo in front of the Joe Pagac mural at Campbell Avenue and Grant Road, the whales flying through the desert are symbolic of the ability to thrive even in a harsh environment.

Photo courtesy of Curtis Thorne

Thorne, who created the design himself, says the sharpened edge on the base of the T is intentional, evocative of that thorn in your side, the thing that causes pain and suffering.

“In some ways, it’s a symbol of facing the fear of cancer and voluntarily facing it head-on. That’s what we do,” said Thorne, who is the director of the graduate program in molecular medicine at U of A College of Medicine – Tucson. “As scientists, we tackle something that’s hard, that we don’t know how to solve.”

His lab studies the basic biology of tissue renewal in the gastrointestinal tract – which in a healthy intestine turns over every five or six days – and how it can morph into cancer. The focus is on drug discovery, and the lab made a major breakthrough, discovering the compound CHIC895 that targets vulnerabilities in colorectal cancer in collaboration with the lab of Christopher Hulme, PhD, a professor of pharmacology and toxicology in the U of A’s R. Ken Coit College of Pharmacy.

The Thorne team works collaboratively with clinicians, which isn’t always the norm, Thorne said. He said he’s thankful to work so closely with doctors because biologists tend to lavish their attention on cells while the physicians focus on the patients made up of those cells and who also must deal with a treatment’s side effects. Thorne knows that all too well.

“I've had these old, nasty chemos in my body. I felt how terrible that is – how that’s not living,” said Thorne, whose cancer was diagnosed when he was in his 30s. “There was life for me because of it, so I’m thankful.

“I really don’t go a day without thinking about my brothers, and I don’t go a day without thinking about my experience with cancer. That’s also what makes me smile every day – to know that it’s a war that my brothers fought and then I had to fight. Now I have a job that can make that war go away.”

As hard as Thorne is battling to find a cure for cancer, he also knows the disease may well be around forever.

“It’s like gazing at the thorn in your side, knowing that we will suffer, all of us,” he said. “Part of living is accepting that there is suffering. There’s some freedom involved there, and that, to me, turns out to be optimism.”

Finding the silver lining

Thorne’s story of losing his older brothers too young and surviving cancer himself isn’t one he goes out of his way to share.

“People don’t want to hear about the bad stuff,” he said with a shrug.

Ask him, though, and he’ll tell you. Thorne understands that others have similar stories, and maybe his experience can help someone else get through a hard time.

“I’m glad to help in that way,” said Thorne, who’s also a member of the BIO5 Institute. “At this stage of life, I’m trying to be an open book.”

Though he spends his days in a sterile lab, Curtis Thorne loves gardening and originally planned to study botany in college.

Photo by Kris Hanning, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

Thorne’s parents were missionaries, working for Wycliffe Bible Translators in Indonesia. Both his brothers were born overseas. When it became clear his oldest brother had developmental and health issues that would be hard to treat there with limited health care access, they moved to the Dallas suburb of Duncanville, Texas.

The family of five spent a lot of time in the children’s hospital, but outside its white walls, Thorne was a solid B student and self-described band nerd who excelled at science. He was never interested in medicine, though. Thorne loves dirt, working with his hands, the smell of soil and greenhouses.

At Baylor University, a botany major didn’t exist, but he took every class he could on the subject. It was during his senior year that Thorne’s oldest brother, who dealt with tumors in his brain and spine and suffered from the debilitating effects of radiation, passed away.

Tragedy struck the family again when Thorne’s middle brother was diagnosed with cancer in his 20s and died.

Then, the unthinkable happened again. Thorne was slapped with his own cancer diagnosis during his postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Texas Southwestern. He underwent chemotherapy in the same building where he worked.

“It was weird to be a cancer researcher and then go down to the second floor and get chemo delivered to my vein,” said Thorne.

At the most critical point in his career, he was too sick to go into the lab. He couldn’t even get out of bed. While the science of cancer research helped to cure his body, Thorne’s deep faith cared for his mind.

“What I came up with is, all I can do is have faith that God is in control,” he said.

Accepting failure

Thorne is all about living a simple life. He bikes to work and loves plucking the ripe figs off the tree in his yard and turning them into jam. He and his wife, a high school teacher, are working on setting up a garden where they can grow their own food.

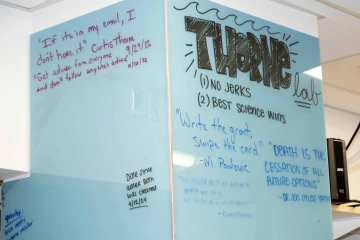

The two Thorne Lab rules are listed in this space along with any quotes students jot down that they think are interesting or funny.

Photo by Noelle-Haro-Gomez, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

After spending his days in a sterile lab, wearing gloves, he welcomes any chance to dig in the earth. Working in a lab can be incredibly frustrating, so the only way to get through it is to be a positive thinker. As successful as Thorne is, his humility keeps him grounded.

“Research, in general, is mostly failure,” Thorne said. “Daily, we come into the lab. We set up complicated experiments. We try to set up all the right controls, and something fails. It’s hard stuff. It’s complicated. Something you think should only take a week takes two months. There’s failure all the time in science.

“And the people who struggle the most are those who can’t deal with that amount of failure. The only option is to be an optimist. My perspective is what a joy it is to be doing what we do. We get paid to show up to a room and ask a tough question about a disease and try to solve it, with the long-term goal of easing the pain and suffering others feel. That’s just a joy to do. That’s worth your time.”

Work can be hard and frustrating, but if you look at the Thorne Lab website, specifically under the heading of “oddities,” you’ll see graduate and undergraduate students and scientists smiling together in a bowling alley or laughing over pizza. They make time to bond and blow off steam. You must, Thorne said, in their line of work.

Community is important to Thorne. It’s important in your personal life, in your work and most definitely when you’re fighting cancer.

“There are multiple ways to make an impact on cancer,” he said. “One is to discover some gene that’s critical for cancer or to discover a therapeutic, but it’s probably as important to understand that cancer is with us and that the most helpful thing is to love and support each other and to be aggressive about loving and supporting each other – and that’s the hardest thing of all.”