Streamlining Schizophrenia Diagnosis with a Simple Test

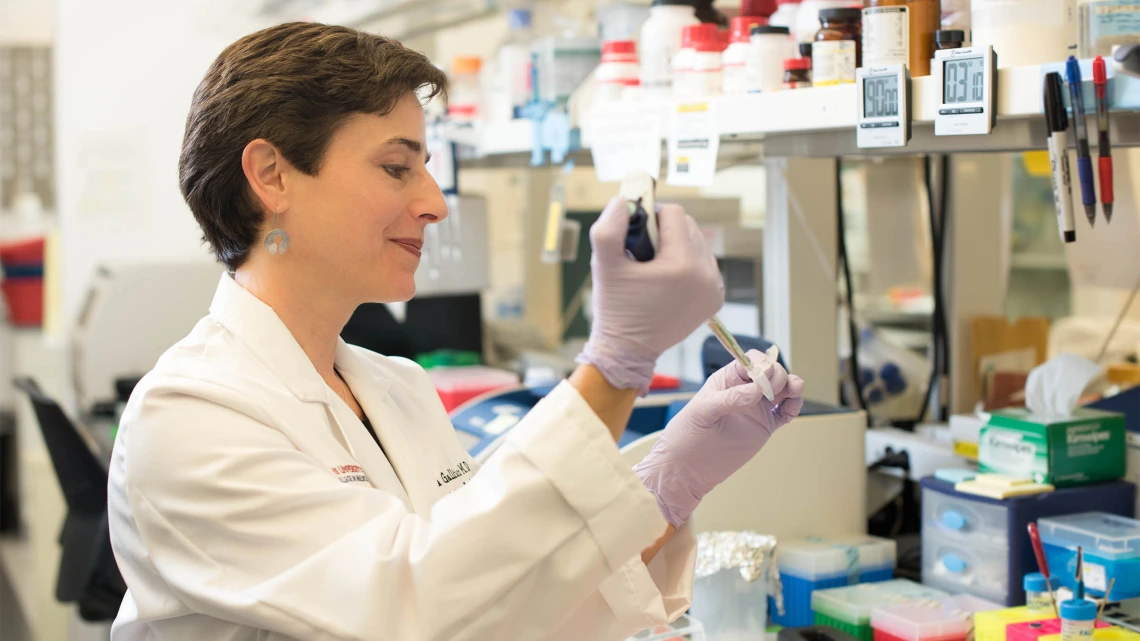

Dr. Amelia Gallitano is shining a light into some of the most difficult-to-reach corners of the human psyche.

Dr. Amelia Gallitano is hard at work developing a diagnostic test for schizophrenia that can be administered by a non-specialist.

Ever since high school, Amelia Gallitano, MD, PhD, professor of basic medical sciences at the College of Medicine – Phoenix, has been fascinated by the brain.

Dr. Amelia Gallitano says her lab is “doing something totally new.”

“The idea that the things we think and feel are determined by the biology that’s happening in our heads really intrigued me,” she recalled.

Her curiosity propelled her toward a medical degree and a doctorate in neuroscience. Soon after, Dr. Gallitano narrowed her research focus down to identifying genes involved in mental illness — which could be a first step toward developing better diagnostics and treatments, or preventing it altogether.

“We don’t know the genes that cause any mental illness,” she said. “In not having yet identified the causes of our illness, the field of psychiatry is way behind other areas of medicine.”

A tricky diagnosis

Dr. Gallitano is especially interested in schizophrenia, a serious disorder characterized by hallucinations, delusions or disordered thinking. Its root causes are shrouded in mystery, and with no quick diagnostic test, schizophrenia is difficult to identify.

Schizophrenia is diagnosed by highly trained specialists.

Rather than undergoing a lab test, patients who might have schizophrenia are evaluated by a specialist, who conducts interviews and pieces together the symptoms that distinguish schizophrenia from other conditions. The need for a specialist represents a bottleneck in the treatment process, which can take months or even years — not just in developing countries, but also across the United States, where a shortage of specialists makes for long waiting lists.

“Psychiatrists are limited in number. It can take six to eight weeks to get an appointment,” Dr. Gallitano said. “We need an expert to diagnose it based on a constellation of symptoms that aren’t the same for every patient, and can exist in other psychiatric illnesses or medical illnesses caused by a medical problem.”

Testing a hypothesis to create a test

If schizophrenia could be identified by a non-specialist, people with the condition could begin appropriate treatment sooner.

“A biologically based diagnostic test would be a much faster way to diagnose somebody, could be done inexpensively and in any clinical setting by people who aren’t experts,” Dr. Gallitano said.

Dr. Gallitano and her team have pulled together several observations to create a hypothesis. The first is that people with schizophrenia, when experiencing psychosis, have a high tolerance for antipsychotic medications.

Schizophrenic people are likely to have low levels of a receptor called serotonin 2A, interfering with the brain’s ability to transmit information from one neuron to another.

“These medicines are extremely sedating,” Dr. Gallitano said. “Compared to individuals who don’t have schizophrenia, a patient with schizophrenia can tolerate 10 times, even 100 times the dose without becoming sedated.”

When studying this phenomenon in mouse models, Dr. Gallitano’s team made a second observation: Mice deficient in a receptor in the brain, called the serotonin 2A receptor, also had a high tolerance to these medications.

“It turns out that, when we look at the literature, low serotonin 2A receptors have been reported in the brains of patients with schizophrenia,” Dr. Gallitano said. These receptors can be visualized on PET scans, expensive and invasive tests that are not used to diagnose schizophrenia.

A third observation showed that mice with reduced serotonin 2A receptors, when given the antipsychotic medications, have a “signature” pattern on EEGs, or electroencephalograms, a test that measures electrical activity in the brain.

After stringing these three observations together, the Gallitano Lab is investigating the links between schizophrenia and low levels of the serotonin 2A receptor, high tolerance for antipsychotic medication and a telltale EEG signature, in the hopes of distilling these phenomena into a “checklist” that could allow clinicians to diagnose schizophrenia simply by administering the medication to a patient and observing their response.

Streamlining a diagnosis

In preparation to maximize the impact of the innovation through possible commercial pathways, Dr. Gallitano worked with Tech Launch Arizona, the university’s commercialization arm, to patent this checklist, and her team launched a clinical trial to test its accuracy. If their hypothesis is correct, clinicians could sidestep schizophrenia’s time-consuming diagnostic process, for example when a patient presents to the emergency department with symptoms indicative of schizophrenia.

As an MD-PhD, Dr. Amelia Gallitano spends time in both the clinic and the lab.

The Gallitano Lab completed early studies on people without schizophrenia, which allowed them to select a medication that is highly sedating in people without schizophrenia, and helped them translate their previous findings in mice to the new data generated from humans. Before the COVID-19 pandemic put their clinical trial on temporary hold, the tests laid the groundwork for further studies in participants with schizophrenia.

Dr. Gallitano, who is also a member of the BIO5 Institute, looks forward to resuming these studies as soon as she can. If they reveal different responses to the medication in people with schizophrenia versus control subjects, they’ll investigate whether tolerance to the medication correlates with low serotonin 2A receptor levels, which themselves are correlated with schizophrenia.

“It’s measuring something easy to measure — how sleepy you get after a drug — but telling us something that’s very hard to measure, which is levels of a certain receptor in the brain,” Dr. Gallitano said. “We’re doing something totally new.”