Thousands of Arizonans to Contribute to 2-Year COVID-19 Study

A cross-campus collaboration spearheaded by the College of Public Health seeks to understand ‘long COVID’ and other coronavirus mysteries.

After more than a year since its earliest documented appearance, much remains unknown about SARS-CoV-2. The lack of actionable data about the novel coronavirus, which threw the world into a pandemic, has prompted the University of Arizona Health Sciences to undertake the first statewide long-term public health study of COVID-19: the Arizona CoVHORT study. The research effort is intended to shed light on infection risk and the recovery process to improve care for patients touched by this crisis.

Kristen Pogreba-Brown, PhD, MPH, trains public health graduate students to conduct outbreak investigations.

“This was the brainchild of my colleagues and I working together to see what we can do to help,” said Kristen Pogreba-Brown, PhD, MPH, a Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health assistant professor. “In some ways, we did this as therapy. We needed to feel like we were doing something.”

CoVHORT involves faculty, staff, and students from the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, College of Medicine – Tucson and College of Medicine – Phoenix, as well as team members from other UArizona colleges and Arizona State University. The group’s goal is to include 10,000 Arizonans in the study, and so far they have enrolled more than 3,000 participants, including 622 confirmed COVID-19 cases.

Shedding light on lingering symptoms

The “acute” phase of COVID-19 can last several weeks, after which many patients recover and move on with their lives. But some people, despite no longer having detectable levels of the virus, continue to experience health problems, such as fatigue and body aches — or worse. Dr. Pogreba-Brown calls this phenomenon “long COVID,” though people suffering from it have dubbed themselves “COVID long-haulers.”

Grad students on the CoVHORT team assemble thank-you packets for study participants outside Drachman Hall.

“People who have COVID-19 don’t always recover quickly, and we’re starting to see different symptoms emerge,” Dr. Pogreba-Brown said. “We knew the mortality rate was bad. What we didn’t know at the time was what the morbidity would end up being.”

The media has reported on a variety of potential manifestations of long COVID, from loss of smell to COVID toes. Collin Catalfamo, MPH, public health doctoral student and graduate research associate, points to the virus’s structure as the culprit.

“The virus takes advantage of a protein that’s expressed in a lot of different tissues,” Catalfamo said. “That’s why it’s able to make someone lose their sense of smell, because it’s able to invade that nervous tissue. Some people are getting heart problems, because it’s able to invade that heart tissue.”

Designing the two-year study

To answer questions about long COVID, CoVHORT brings together two groups: infectious disease epidemiologists and chronic disease epidemiologists. Traditionally regarded as distinct entities, there can be overlap between infectious and chronic diseases, such as when an infectious disease like human papillomavirus infection leads to a chronic disease like head-and-neck cancer.

“While we get along fabulously, chronic disease epidemiologists and infectious disease epidemiologists think about disease in different ways,” Dr. Pogreba-Brown said. “We had to figure out how to merge our methodologies so we could think about how an infectious disease could be triggering chronic outcomes. It’s really challenging to study these connections.”

CoVHORT is named for its object of inquiry (coronavirus, or CoV) and its design (cohort study). While clinical trials have dominated headlines lately, thanks to the race to FDA approval between several COVID-19 vaccines, cohort studies are “natural” clinical trials, taking advantage of current events to compare one group to another.

“In a clinical trial, two groups are randomized to receive treatment versus not. They follow those people over time,” Catalfamo explained. “Cohort studies are somewhat similar, but we’re not purposely exposing someone to the virus — we know some people are going to be exposed. We’re just leveraging that.”

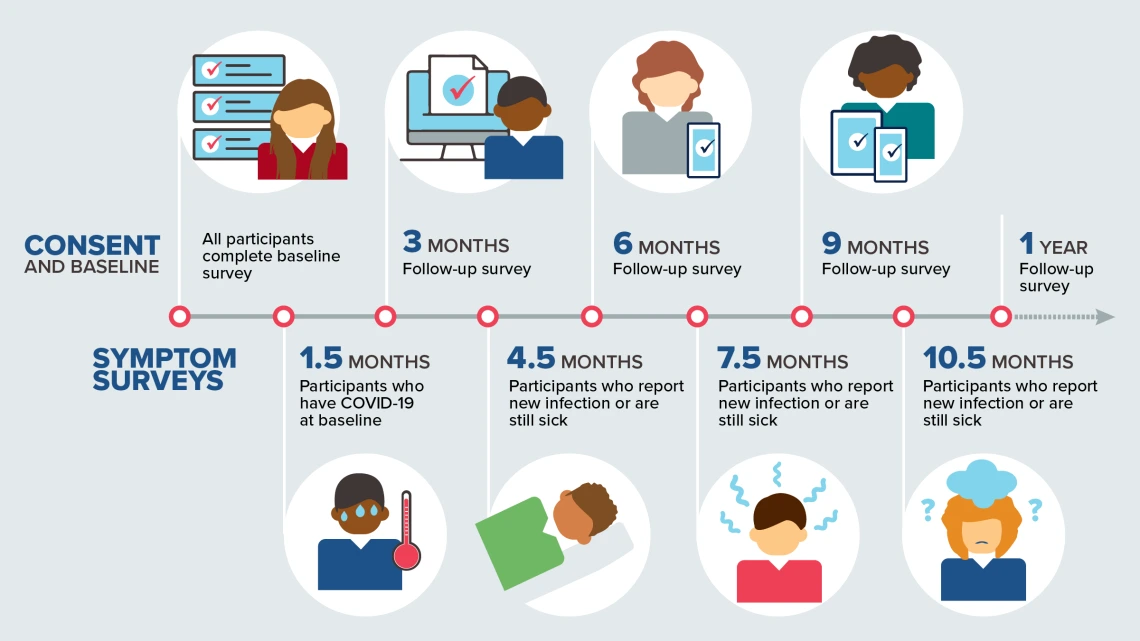

All CoVHORT participants will receive quarterly surveys for two years, and those who have tested positive for COVID-19 will complete additional questionnaires to track symptoms over time.

CoVHORT will follow participants for two years, comparing people with and without COVID-19 to uncover risk factors for infection and paint a fuller picture of symptoms and recovery.

Casting a wide net

A collaboration with Karen Lutrick, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine, will reach patients who tested positive for COVID-19 but whose symptoms weren’t severe enough to require hospitalization, which Dr. Pogreba-Brown hopes will address a weakness in many other COVID-19 studies.

“A lot of the studies involve hospitalized patients, but we have far more people who get sick enough to go to their primary care provider, but not sick enough to be hospitalized,” Dr. Pogreba-Brown said. “Because they never go to the hospital, they’re never recruited into those studies. From a research perspective, they’re ignored. Hopefully, we can tell a broader story of the impacts of COVID on the whole population.”

Public health doctoral student and epidemiologist Erika Austhof, MPH, foreground, helps other grad students assemble thank-you packets for study participants in a physically distanced setting outside Drachman Hall.

The team is contacting potential participants through contact tracing, mailings and flyers, the University of Arizona antibody testing study, Arizona State University COVID-19 testing clinics and word of mouth. Catalfamo says overwhelming public concern is making it easier to recruit participants than it might have been otherwise.

“We’re in a unique situation, because COVID-19 is so novel that a lot of people want to help in any way they can,” Catalfamo said. “People who have seen its effects up close and personal are that much more willing to participate in the research.”

Studies like CoVHORT are the first step in the scientific process: gathering observations. By characterizing what COVID-19 looks like in a representative slice of the population, CoVHORT will allow researchers to make and test hypotheses to provide desperately needed information about risk factors and ongoing treatment for this emerging disease.

“We’ve known that masks and physical distancing work since the 1918 flu pandemic. Everything we learn from each pandemic helps inform the next one,” Catalfamo said. “Even though we’ve been at this for almost a year in the U.S., there’s still a lot we don’t know.”