A Difficult Conundrum: Genetic Testing for Alzheimer’s Disease

Do I really want to know? This is one of the most important questions people ask themselves before genetic testing. And this conundrum is more relevant for conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

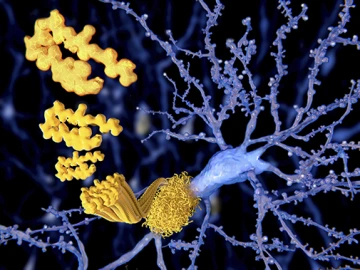

Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that over time results in the loss of memory and thinking skills, eventually affecting a person’s ability to carry out basic tasks. Although treatments are available that may help slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, there is currently no cure.

Researchers still are untangling the complicated web of risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. The most significant risk factor is age, but we know that genetics, environment and lifestyle also play significant roles in a person’s overall risk.

The most significant risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease is age, but genetics, environment and lifestyle also play significant roles in a person’s overall risk.

The best understood genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease lies in a gene called apolipoprotein E (APOE). Everyone has two copies of the APOE gene, one inherited from the mother and the other from the father. The APOE gene has multiple different forms, called alleles. APOE has three common alleles: e2, e3 and e4. People who have one or two copies of the APOE e4 allele have an increased risk of developing late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. The risk increases in people with two copies of the APOE e4 allele. In addition, people who carry APOE e4 alleles tend to develop Alzheimer’s disease earlier than those who do not, though typically after age 60.

Genetic tests are available that can tell you and your doctor which alleles you carry and this information can help determine if you are at increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. However, there are important considerations to think about before pursuing genetic testing for Alzheimer’s disease.

- There are additional genes that affect the overall risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Testing for only the APOE alleles does not provide a complete picture of someone’s genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease.Image

Genetic tests are available that can tell you and your doctor which alleles you carry and this information can help determine if you are at increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

- Lifestyle also impacts the risk of developing Alzheimer’s. Physical exercise, a healthfuldiet and brain exercise are some of the things that you can control to reduce Alzheimer’s risk.

- Limited options are available for treatment, and genetic testing can cause a significant emotional burden for patients and their families.

- Government protections against discrimination using genetic information only cover health insurance and employment. Results of genetic testing can be used by long-term care, life or disability insurance companies to disadvantage people believed to be at higher risk.

Regardless, many people really do want to know. Pursuing genetic testing for Alzheimer’s can help certain people better understand their risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and provide an incentive to adopt habits that can help reduce risk.

In the end, the decision to pursue genetic testing for Alzheimer’s disease is up to each individual. Learning as much as possible and consulting with experts, like physicians and genetic counselors, can help people make an informed decision that works best for them.

Currently, a definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease can only be made after a person has died, by identifying the telltale amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in postmortem brain tissue.

The UA is a leader in Alzheimer’s disease research, and other neurological conditions. The Center for Applied Genetics and Genomic Medicine works with experts in neurological genetics and partners with the Center for Innovation in Brain Science and the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute to use precision medicine to improve the lives of patients with a variety of neurological conditions.

To learn more about the precision medicine initiative at UA, please visit http://precisionhealth.uahs.arizona.edu/.

About the Author

Valerie Schaibley, PhD is the Administrator for the Center for Applied Genetics and Genomic Medicine at the University of Arizona Health Sciences, where she works to advance precision health in the state of Arizona. She received her PhD in Human Genetics from the University of Michigan and worked for several years in industry, developing genetic tests for precision medicine applications.

About the Author

Kenneth S. Ramos, MD, PhD, PharmB, served as associate vice president for precision health sciences at the University of Arizona Health Sciences, director of the Center for Applied Genetics and Genomic Medicine and the MD-PhD Program, and professor of medicine. In 2019, Dr. Ramos accepted a position as executive director of the Institute of Biosciences and Technology in Houston and assistant vice chancellor for Health Services at The Texas A&M University System.

Dr. Ramos is a physician-scientist with interests in molecular and precision medicine, particularly as it relates to vascular pathology, oncology and chronic diseases of the lung. His translational research program integrates diverse approaches ranging from molecular genetics to population-based studies to elucidate genetic and genomic mechanisms of pathogenesis, and to develop novel approaches and therapies to minimize chronic diseases caused by environmental injury. Ongoing translational studies in his laboratory focus on the study of repetitive genetic elements in the mammalian genome and their role in genome plasticity, toxicity and disease, while clinical studies focus on the development and characterization of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of cancer and chronic pulmonary disease to advance the goals of personalized genomic medicine. He has directed two NIH P30 Centers of Excellence working at the interface between genomics and environmental health and medicine and have provided administrative and scientific leadership for two academic centers focusing on genetics and genomic medicine. He has influenced the career of many scientists through my involvement in several NIH-funded training and career development programs where he has mentored over 100 doctoral, medical, veterinary, undergraduate and high school students, many of whom have gone on to successful careers in academia, medicine, government and industry. He is deeply committed to initiatives that advance precision medicine and its applications to reduce disease burden and health disparities, improve quality of healthcare and reduce costs.