Art, music, science combine for unparalleled experience

Hearing the Invisible engaged the community in science through art, music and an unprecedented opportunity to listen to the sounds of brain waves.

For Hearing the Invisible, the University of Arizona’s Tornabene Theatre was converted into a multimedia representation of a brain using special lighting, images projected onto the walls and ceilings, and colorful columns of flowy fabric representing the various nodes of the brain.

Photo by Kris Hanning, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

In mid-February, “Hearing the Invisible” gave Tucson community members the rare opportunity to listen to what could previously only be seen: brain waves captured by electroencephalograms, or EEGs. The innovative science and art collaboration examined the diagnostic power of audio of brain activity from healthy individuals and those with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

“We played the audio files over the loudspeaker so we could walk people through what a normal brain sounds like and then what the Alzheimer’s brain or the dementia brain sounds like,” said Tally M. Largent-Milnes, PhD, a member of the University of Arizona Health Sciences Comprehensive Center for Pain & Addiction and an assistant professor in the U of A College of Medicine – Tucson’s Department of Pharmacology. “One is smooth, and one is choppy. People were describing it as sounding like a starter trying to turn over or stuttering for the Alzheimer’s brain versus like whale sounds and smooth waves for the normal brain.”

Alpha Brain Waves

Healthy Brain

Dementia Brain

Alzheimer's Brain

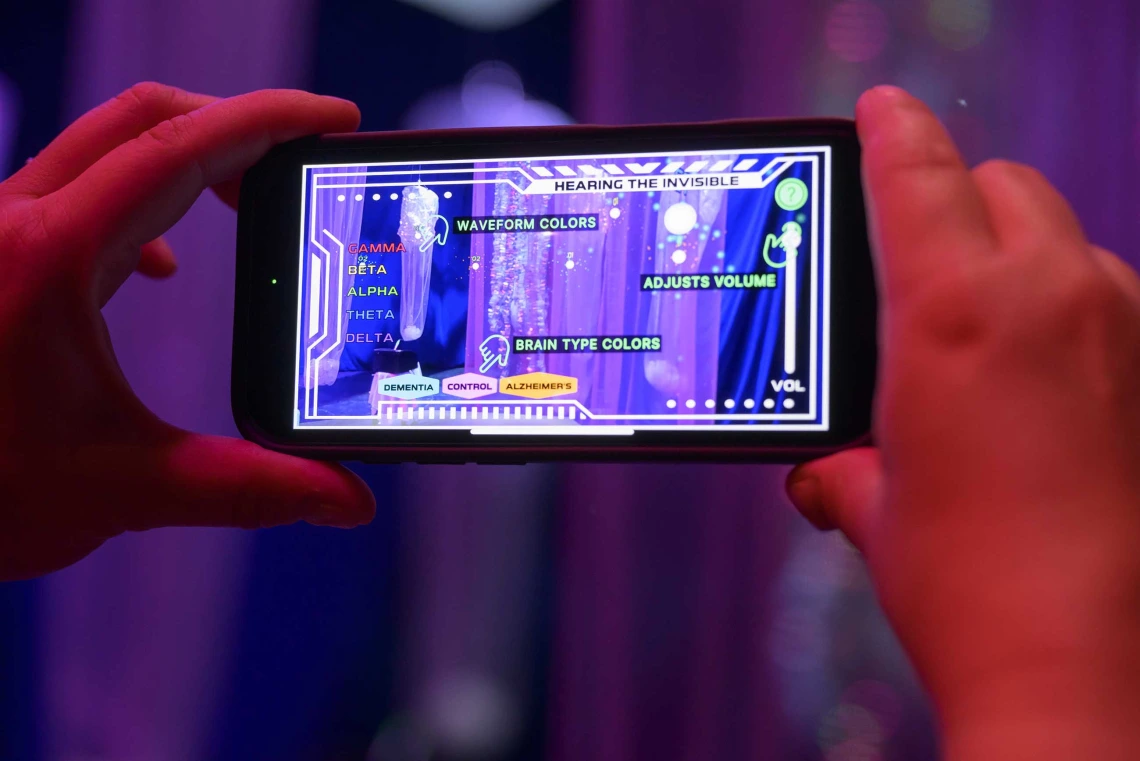

The immersive installation featured the beginning stages of the work of Largent-Milnes and professor Cynthia Stokes, MFA, of the U of A College of Fine Arts’ School of Music. Attendees used an augmented reality app to explore the brain’s structures and functions while listening to audio readings of five individual brain waves from healthy, Alzheimer’s and dementia brains sonified into music by composer Michael Vince. At scheduled times, singers from the U of A School of Music performed the composition live for the audience.

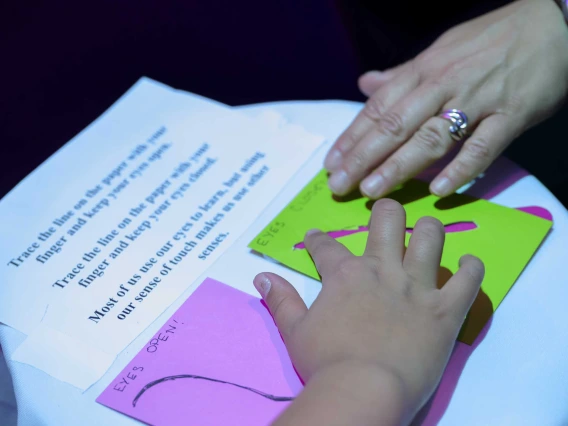

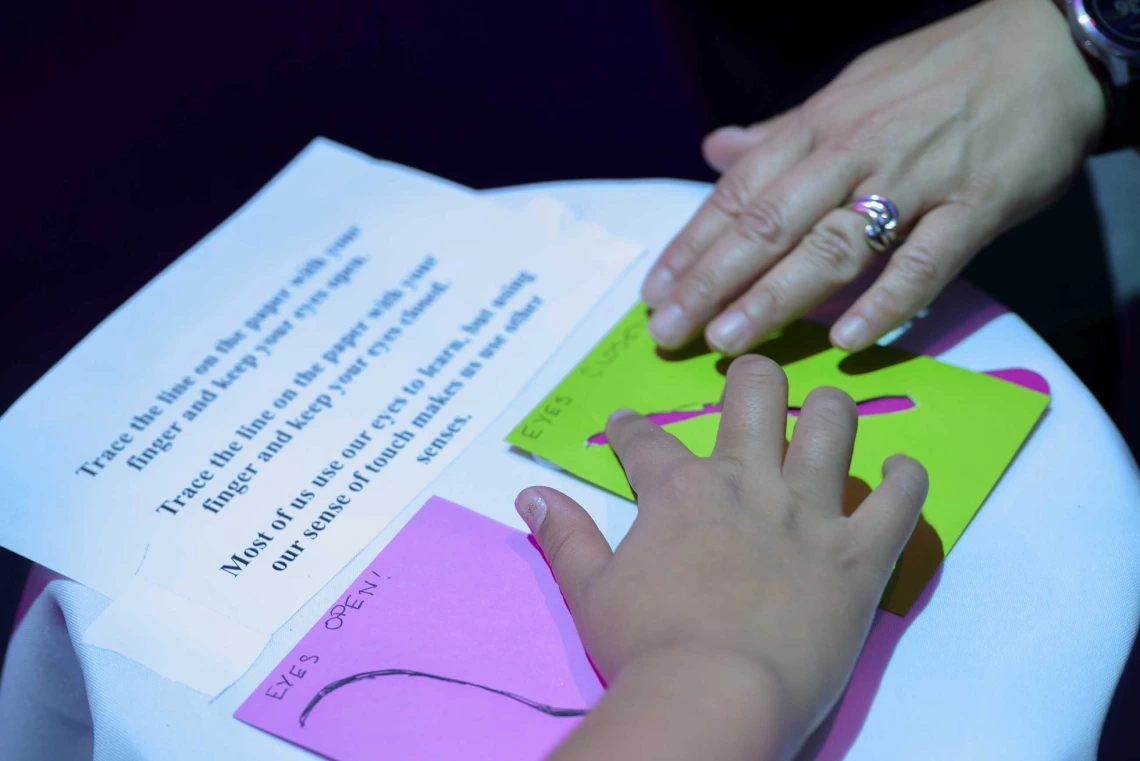

The event also featured a walkable audiovisual installation, interactive memory and other brain games that highlighted what the various nodes of the brain do, displays of art and research posters, and educational information about the brain.

“Overall, it was a good event. I think people really liked it,” Largent-Milnes said. “From a research standpoint, this was proof of concept for the installation and the sound that EEGs make. You can hear the different disease states, at least in the examples that we have.”

Largent-Milnes hopes to expand the research to determine if the changes will be consistently heard in more EEGs and if the brain waves are changing in predictable ways. Eventually, she would like to perform the same proof of concept using EEGs from people with chronic pain.

“Normally when we think of diseases, there’s a physical change you can see with advanced imaging. But with neurological diseases, by the time you can see something on an MRI, it’s too late to do anything,” she said. “In dementia, you have a loss of brain matter. In chronic pain, you have a brain that looks older than it actually is in chronological time.

“With invisible diseases, just because someone looks fine doesn’t mean they are fine. That’s why Hearing the Invisible was born – to make EEG waves audible for diseases that are invisible.”

Beta Brain Waves

Healthy Brain

Dementia Brain

Alzheimer's Brain

Delta Brain Waves

Healthy Brain

Dementia Brain

Alzheimer's Brain

Gamma Brain Waves

Healthy Brain

Dementia Brain

Alzheimer's Brain

Theta Brain Waves

Healthy Brain

Dementia Brain

Alzheimer's Brain

Experts

Tally Largent-Milnes, PhD

Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacology, U of A College of Medicine – Tucson

Member, BIO5 Institute

Related Stories

Contact

Stacy Pigott

U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

520-539-4152, spigott@arizona.edu