Finding a nutritious solution to a climate change challenge

Researchers are addressing food insecurity for people around the world by studying a desert bean that needs little water and withstands harsh environments.

Tepary beans are high in protein, packed with micronutrients, and thrive in harsh desert climates, making them a promising solution to food insecurity related to environmental changes.

Photo by Kris Hanning, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

In 2022-23, Duke Pauli, PhD, planted rows of tepary beans at the University of Arizona’s Maricopa Agricultural Center, where many plants still turned out “green and happy” despite a scorching heat wave.

Photo courtesy of Duke Pauli, PhD

Imagine being in a nearly constant state of hunger, never knowing where your next meal will come from. Food insecurity – when quality food is unaffordable or unavailable – affects billions of people around the world. In 2023, around 2.33 billion people globally faced moderate or severe food insecurity, according to the United Nations’ State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report released July 24. Among those, over 864 million people experienced severe food insecurity, going without food for an entire day or more at times.

Organizations such as the UN, the Environmental Protection Agency and the World Health Organization call climate change a major driver of food insecurity and say it has the potential to make the situation even worse.

Climate change indicators such as rising temperatures, more frequent heat waves and prolonged droughts, can affect plant growth, agricultural production, and the spread of plant diseases and pests – all of which present threats to food quality and supply.

Addressing the challenges of climate change and human health is a strategic priority of the University of Arizona Health Sciences, which is funding research into a particularly resilient and nourishing crop – the tepary bean.

A new look at an old plant

The tepary bean has been harvested for thousands of years by Indigenous peoples in harsh desert climates including the southwestern United States, northwest Mexico, and parts of Central America. The name tepary comes from the Tohono O’odham word pawi, which means “bean.” Several properties make the plant, which is traditionally planted to coincide with monsoon rains, well adapted to the otherwise hot and dry conditions of the Sonoran Desert.

(From left) Duke Pauli, PhD, and Betsy Arnold, PhD, grow tepary beans and study the crops with the goal of optimizing nutritional content and agricultural production to fight food insecurity around the world.

Photo by Kris Hanning, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

“It is truly amazing what this plant can do, and it is very different from pretty much any other crop you can think of,” said Duke Pauli, PhD, associate professor at the U of A College of Agriculture, Life and Environmental Sciences School of Plant Sciences. “Teardrop-shaped leaves radiate heat away from the plant, and those leaves can also turn to avoid the full force of the sun in middle of the day. When the plant flowers, the flowers form under the shady canopy toward the middle of the plant, where it is coolest. It also sets deep roots so it can chase any water available.”

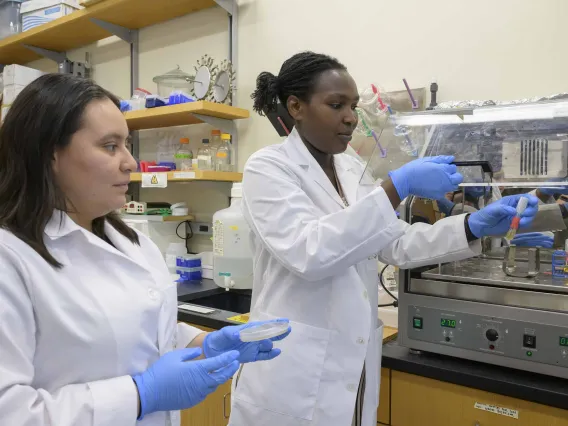

Pauli and Betsy Arnold, PhD, interim director of the School of Plant Sciences at the College of Agriculture, Environmental and Life Sciences, are learning more about the tepary bean by growing more than 200 varieties in a field about 100 miles from the University of Arizona’s main campus in Tucson.

“Here in Arizona, our knowledge community is uniquely poised to address the dilemma of providing food in a hot, dry environment,” Arnold said. "Working together, and with respect for the origins and importance of this food source, we can grow partnerships with lasting impacts for climate-vulnerable populations.”

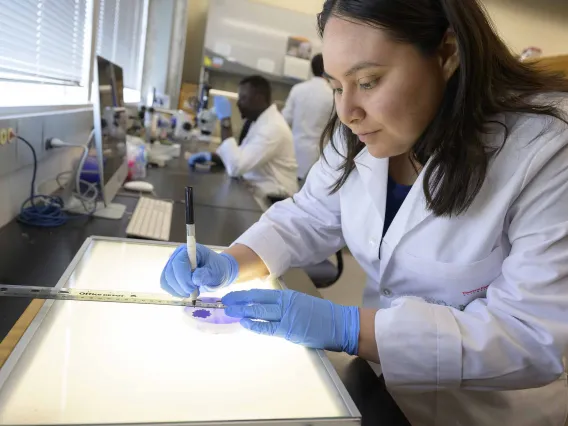

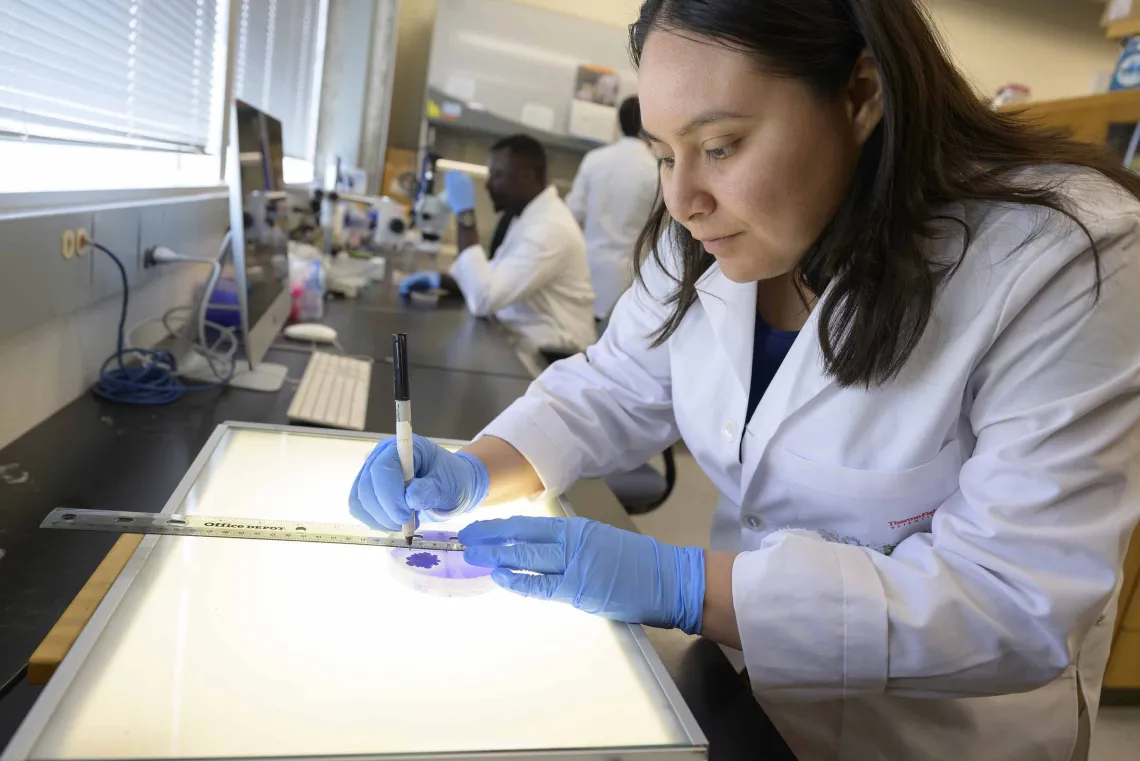

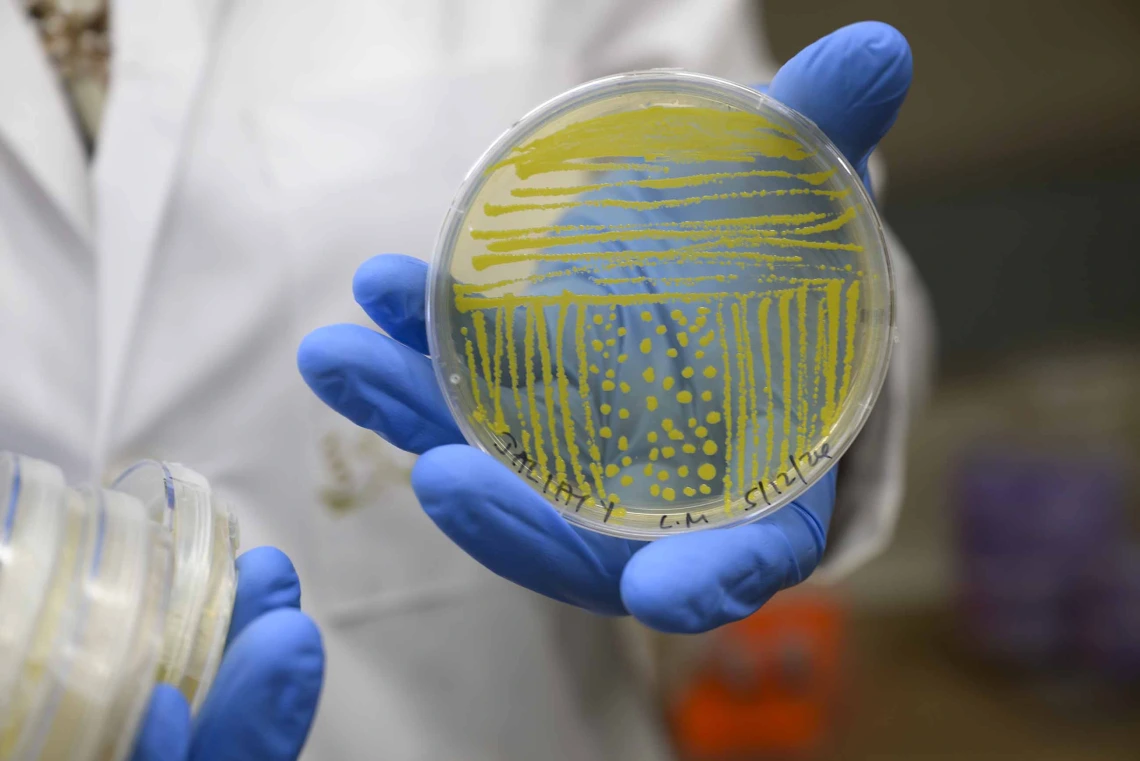

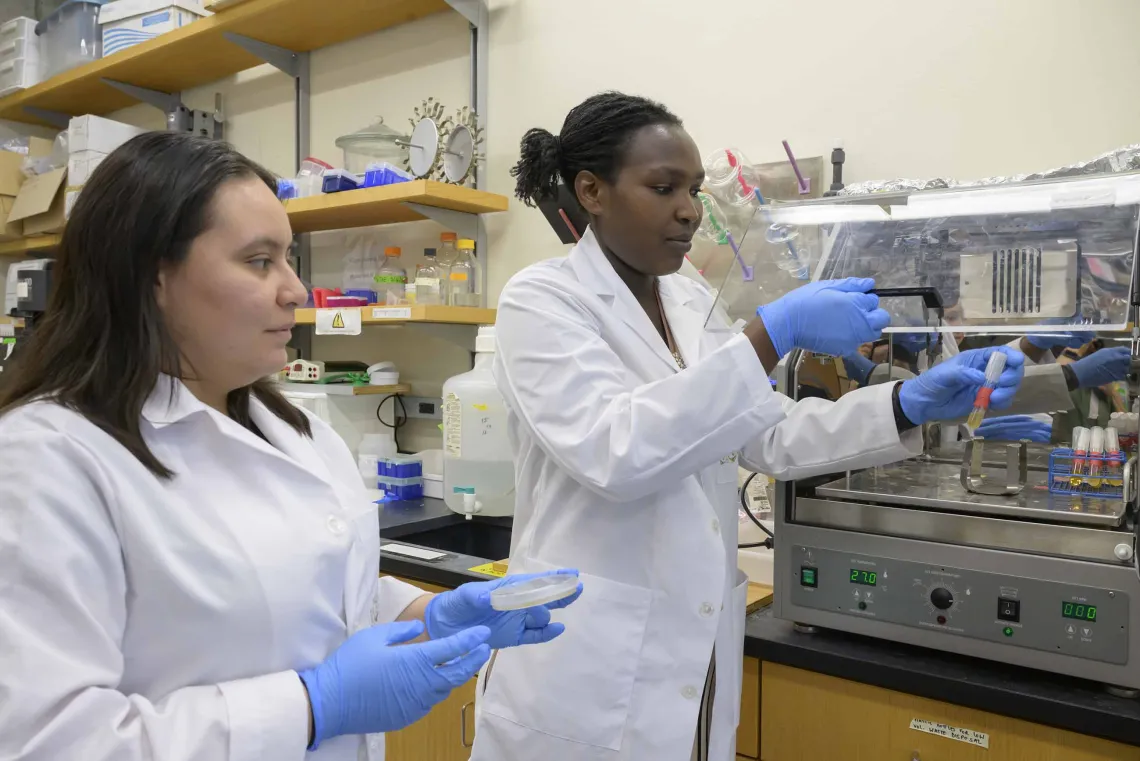

Betsy Arnold, PhD, and graduate student Joshua Oyekanmi are analyzing tepary bean microbes with a goal of finding a way to boost crop production.

Photo by Kris Hanning, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

Using beans bred over many years by the United States Department of Agriculture, the team is investigating genetic variations that affect traits such as growth rate, the greenness of the plant and leaf shape, and examining how they impact the amount and quality of beans produced.

Sixty to 90 days after planting, and with minimal bi-weekly watering, the plants will produce a bean that is packed with nutrition.

“Legumes, a type of plant that produce seeds in pods, are considered to be one of the best sources of plant protein. Tepary beans top the list, consisting of up to 30% protein,” Pauli said, adding that the tepary bean has a rich, nutty flavor and smooth texture that set it apart from other types of beans. “Tepary beans are also high in fiber and micronutrients like zinc, calcium and magnesium. And, the leaves can be used to feed livestock.”

After harvesting the beans, Pauli and Arnold will generate nutrition profiles for each of the varieties.

“One of our main goals is to identify which lines of tepary bean are not only tenacious in the face of tough conditions, but also provide a high yield of nutrient-rich beans,” Pauli said.

Giving tepary beans a boost with microbes

Tepary beans can be used in place of any bean in a variety of dishes, including salads, soups, stews, dips and spreads.

Photo by Kris Hanning, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

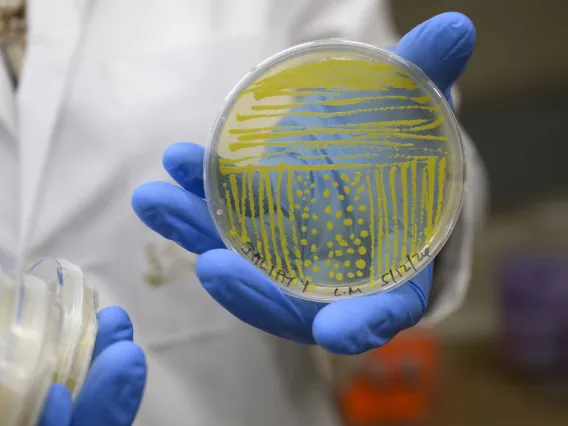

Back in the laboratory, Pauli and Arnold are hoping to give these already impressive beans a helping hand. They are examining the plant’s microbiome and exploring how microbes can be used to improve crop production.

“Plants have microbiomes much like how humans have microbiomes. Just like in people, some microbes can make you sick and others can be beneficial,” Arnold said, explaining that a microbiome is a community of microbes, such as bacteria and fungi, that live in a particular environment. “We’re becoming increasingly aware of how important a healthy microbiome is for plants.”

Microbes can influence how fast a plant grows and how well it can access nutrients in the soil. To really dig into this relationship, the research team used microbes from the beans and roots of high performing plants in previous studies to coat new seeds prior to planting in a process called biopriming.

“We’ll be examining which microbes correspond with which beneficial traits, and it is possible we may find out the microbes help in ways we haven’t even thought of yet,” Arnold said. “The practical application of this could be a new method farmers can use to boost their chances for a plentiful tepary bean harvest.”

The agriculture industry will be under pressure from a changing climate, but Pauli and Arnold say the tepary bean has a proven track record of providing sustenance under intense conditions. They hope applying scientific vigor to the plant will make it an even more resilient and reliable crop, ensuring nutritious foods will be available and attainable to the most vulnerable populations.

“Part of the beauty of this solution is its simplicity,” Pauli said. “Dry beans are already used in areas of the world with food insecurity. Tepary beans can be easily integrated onto a plate and into someone’s diet.”

Experts

Duke Pauli, PhD

Associate Professor, School of Plant Sciences, College of Agriculture, Life and Environmental Sciences

Director, Center for Agroecosystems Research

Betsy Arnold, PhD

Interim Director and Professor, School of Plant Sciences, College of Agriculture, Life and Environmental Sciences

Curator, Robert L Gilbertson Mycological Herbarium

Member, BIO5 Institute

Related Stories

Contact

Brian Brennan

U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

520-621-3510, brianbrennan@arizona.edu