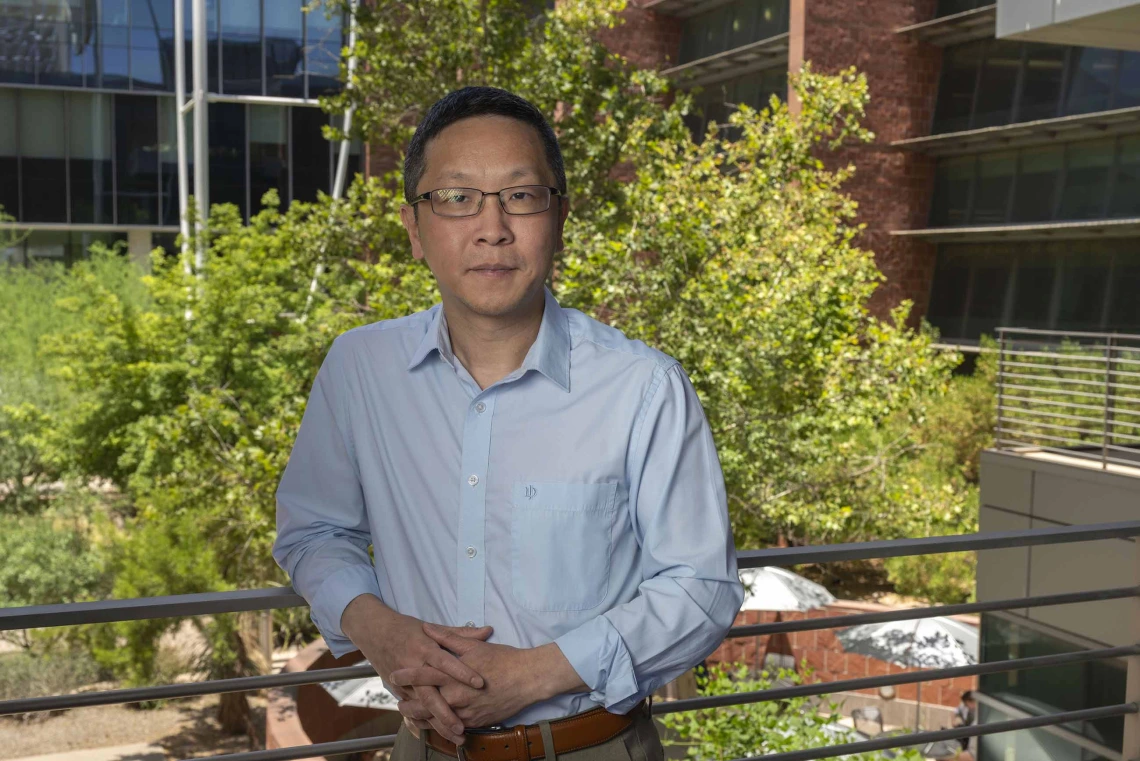

Mingyu Liang works to transform physiology at U of A

College of Medicine – Tucson department head advocates for holistic, innovative approach to ancient discipline.

As the head of the University of Arizona Department of Physiology, Mingyu Liang, MB, PhD, aims to transform the ancient discipline.

Photo by Noelle Haro-Gomez, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

Physiology is one of the oldest biological sciences, and Mingyu Liang, MB, PhD, is busy transforming it for the next generation.

Liang, chair of the University of Arizona Department of Physiology and Cosden professor, is spearheading the Molecular Systems Medicine Initiative. Through the initiative, the renowned scientist has brought together different labs and disciplines with the idea of creating a vision that humans aren’t just a collection of isolated organs but interconnected molecular systems.

“Where I see physiology going in the future is also where I see all biomedical research in general going in the future,” he said. “That is this concept that humans are not just a collection of organ systems or a collection of molecules but instead humans are fundamentally molecular systems.”

It’s not the first time he’s transformed science.

A fresh start

Before Liang came to the U of A in 2023, he thought he had it made.

At the Medical College of Wisconsin, he’d risen to a tenured professor position and served as vice chair for interdisciplinary and translational research in the Department of Physiology. He pulled together collaborators from different disciplines and built a respected lab that focuses on three specific areas of (epi)genomics and precision medicine, regulatory RNA and cellular metabolism, as they relate to hypertension and cardiovascular and kidney diseases. His department had been the top physiology department in the country for years, and he founded the Center of Systems Molecular Medicine.

Mingyu Liang, MB, PhD, says the U of A Department of Physiology aims to advance science and improve health. Liang and lab manager Bhavika Therani review data.

Photo by Noelle Haro-Gomez, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

Still, Liang felt restless.

“I started to think a lot more about not just my own research, but my discipline as a whole,” Liang said. “Physiology is a very old discipline, and sometimes people will say it’s too old, that it will die out, but others think physiology is critical because now we have all the high-throughput tools at the molecular level. We need physiology to bring everything back together.”

So, Liang – and most of his lab’s researchers – made the move to the U of A where he felt he could have a bigger impact.

“I'm excited about growing and developing programmatic research that is relevant to human health,” he said. “I tell my department we are here really to do two things: We are here to advance science and improve health.”

To that end, Liang said he wants the U of A’s physiology department to lead the way, transforming the discipline through “high-impact research and future-focused education.”

The department is well on its way, Liang said.

“National Institutes of Health funding for our department has more than doubled, and our faculty are publishing a lot of high impact research, and enrollment of our physiology courses has continued to grow,” he said.

The U of A has one of the largest physiology undergraduate programs in the United States. It’s unique because it falls under the U of A College of Medicine – Tucson, and few medical colleges offer undergraduate degrees.

Additionally, its introductory courses, Physiology 201 and 202, are among the university’s most popular classes. Liang has also created several programs within the department, including the Program for Visceral and Interceptive Systems Physiology led by Katalin M. Gothard, MD, PhD, which looks at how the body’s internal organs communicate with the brain.

“It’s a new frontier in biomedical research,” he said.

Liang is also proud that in each of the last two years, physiology students received two of the seven awards presented at commencement. Student success is vitally important to him, and he’s mentored many over the years.

“One of the best ways to learn is to work with someone very closely and watch them, watch how they operate on a daily basis,” Liang said. “I learned much more from that experience than what anyone told me in words and lectures and training workshops. Watching how people operate, how they make decisions, how they deal with issues on a daily basis, that taught me a tremendous amount and affects how I do things.”

Liang credits his own mentors with teaching him a valuable lesson he continues to pass on to students.

“It’s possible to be good at what you do and still be kind to people,” he said. “That’s a pretty important lesson that sticks with me all these years.”

Doing what it takes

It’s nothing for Mingyu Liang, MB, PhD, to put in a 70-hour work week, which is fine by him. Liang says when you have fun, going to work feels like a vacation.

Photo by Noelle Haro-Gomez, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

Higher education where Liang grew up was highly competitive, and it was even more so in medicine. While Liang debated between clinical practice and research, he ultimately decided on research. That, he thought, would be a faster way to start making a difference. Turns out earning a medical degree from Shanghai Medical University – a top medical school where he was named an outstanding graduate by the Shanghai Municipal Government – followed by a PhD from Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and then two post doc fellowships wasn’t exactly speedy.

A nephrologist colleague further put things into perspective for Liang.

“He said, ‘You know, clinical work is a lot, but I take care of patients and when I go home, I’m done. As a scientist, you’re never done. You’re always thinking about your scientific problems,’” Liang said.

Too true. While science does occupy much of his day, Liang carves out plenty of time for his three kids. When he can, Liang unwinds by writing poetry and short essays. There hasn’t been much time for that, though.

With all his administrative duties, Liang ends up extending his workday to make time for research. He’s fine with that.

“I enjoy my work and don’t feel stressed working 70 hours a week. To me, going to work is not that different than going on vacation,” Liang said with a laugh. “It’s having fun either way, but that may be because of my ignorance about vacation.”