UArizona Health Sciences Researchers Identify New Target for Developing Flavivirus Vaccines

Antibodies normally fight viruses, but in the case of flaviviruses, they can make infections worse. Researchers took a closer look at antibody production to figure out why.

The results of a recent study moved University of Arizona Health Sciences researchers one step closer to developing effective vaccinations against flaviviruses, which infect more than 400 million people a year with diseases such as dengue, yellow fever, West Nile, Zika and Japanese encephalitis.

Deepta Bhattacharya, PhD (Photo: University of Arizona Health Sciences, Noelle Haro-Gomez)

When a person is infected with a virus, antibodies are produced to fight the virus and provide immunity against reinfection. In the case of flaviviruses, however, if a person gets a second flavivirus infection – they were originally infected with Zika and then got dengue, for instance – the presence of antibodies can result in more severe symptoms through a process called antibody-dependent enhancement of infection.

“If, at some point in the past you’ve had Zika virus, later when you are exposed to dengue, you are at much greater risk of getting sick. Antibodies created by memory B cells as a result of the Zika infection can bind to certain parts of the dengue virus, but the dengue virus isn’t affected,” said Deepta Bhattacharya, PhD, an associate professor in the UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson’s Department of Immunobiology. “In fact, the memory B cell-generated antibodies can work like a ‘Trojan horse’ and help the virus get into the cells, where it can make the disease worse.”

The findings give Dr. Bhattacharya and his team a new way to think about creating flavivirus vaccines. Rather than targeting the whole virus, they propose targeting specific locations on the virus that are unique to each type and strain. Essentially, they would be removing memory B cells from the vaccination equation.

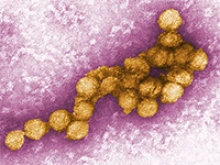

A digitally colorized transmission electron microscopic image of the West Nile virus. (Image: CDC/P.E. Rollin, Cynthia Goldsmith)

“We wanted to study how the immune system and antibody responses deal with sequential exposures to different flaviviruses,” Dr. Bhattacharya said. “Antibody-dependent enhancement of infection is the main reason why it has been difficult to vaccinate against flaviviruses, dengue in particular.”

Dr. Bhattacharya is the senior author on a paper, “Affinity-restricted memory B cells dominate recall responses to heterologous flavivirus challenges,” published today in the journal Immunity. The study focused on two types of cells that produce antibodies: plasma cells and memory B cells.

Plasma cells are the primary drivers of long-lasting immunity, as they continue to produce antibodies once an infection has been cleared or after vaccination. Memory B cells only produce antibodies if a second infection occurs.

Graduate student and co-author Tyler Ripperger and associate professor Deepta Battacharya, PhD, discuss viral assay results. (Photo: University of Arizona Health Sciences, Noelle Haro-Gomez)

“One of the questions we’ve had for a long time is, what is the purpose of those memory B cells?” said Dr. Bhattacharya, also a member of the university’s BIO5 Institute. “If you already have antibodies from plasma cells, why do you need the other cells?”

Using a combination of flavivirus infections, vaccinations and genetic mouse models, Dr. Bhattacharya and his team examined how memory B cells respond to subsequent flavivirus infections.

They found that when memory B cells are activated by a new infection, they produce antibodies that are diverse and capable of targeting viruses that have changed since the first infection, through mutation or infection with a slightly different strain, for example.

“There is a huge amount of hidden diversity in memory B cells. For most viral pathogens, like influenza or SARS-CoV-2, this is a good thing. It means that memory B cells are poised to make new antibodies and deal with mutations if and when they arise,” Dr. Bhattacharya said. “For flaviviruses, this is not so great. We found that memory B cells produce a lot of suboptimal antibodies that could enhance the second infection.”

Deepta Bhattacharya, PhD, studies antibody responses to infections and vaccines, and recently focused his research of flaviviruses. (Photo: University of Arizona Health Sciences, Noelle Haro-Gomez)

Although memory B cells recognize the new virus as a flavivirus and produce antibodies, those antibodies are unable to stop the new virus from infecting cells. In fact, they may actually make the second infection worse.

The same holds true when it comes to vaccinations. Vaccines are designed to stimulate an immune response and prompt plasma cells and memory B cells to produce antibodies against a virus. If a person who never had dengue is vaccinated and develops antibodies, then later becomes infected with a different flavivirus, the antibodies produced by memory B cells in response to the vaccination may increase the severity of the disease.

“For people already immune to one flavivirus, this would avoid engaging these not-so-great memory B cells,” Dr. Bhattacharya said. “For people who never were exposed, it avoids generating this problematic diversity in the first place.”

Co-authors in the UArizona Department of Immunobiology are: Jennifer L. Uhrlaub; Dakota Reinartz; Lucas D’Souza, PhD; Tyler Ripperger; and Janko Nikolich-Žugich, MD, PhD. First author Rachel Wong, PhD, was a graduate student in Dr. Bhattacharya’s lab before tranferring to the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Other co-authors from Washington University are Jennifer Govero, PhD; John M. Errico, PhD; Haiyan Zhao, PhD; Daved H. Fremont, PhD; and Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD. Co-authors Julia Belk and Ansuman Satpathy, MD, PhD, are from the Stanford University School of Medicine, and Mark J. Shlomchik, MD, PhD, is from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

The study was funded in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01AI099108, K08230188, P01AI106695, R01AI132186, R01AI127828 and R01AI073755.

# # #

Another version of this article appears also on the Tomorrow Is Here section of the UArizona Health Sciences website.

NOTE TO EDITORS/WRITERS: Photo, graphic and video assets available here – https://arizona.box.com/s/ujunjbvervg1hktoougfai4odxaoqsq1.

About the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson

The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson is shaping the future of medicine through state-of-the-art medical education programs, groundbreaking research and advancements in patient care in Arizona and beyond. Founded in 1967, the college boasts more than 50 years of innovation, ranking among the top medical schools in the nation for research and primary care. Through the university's partnership with Banner Health, one of the largest nonprofit health care systems in the country, the college is leading the way in academic medicine. For more information, visit medicine.arizona.edu (Follow us: Facebook | Twitter | Instagram | LinkedIn).

About the University of Arizona Health Sciences

The University of Arizona Health Sciences is the statewide leader in biomedical research and health professions training. UArizona Health Sciences includes the Colleges of Medicine (Tucson and Phoenix), Nursing, Pharmacy, and the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, with main campus locations in Tucson and the Phoenix Biomedical Campus in downtown Phoenix. From these vantage points, Health Sciences reaches across the state of Arizona, the greater Southwest and around the world to provide next-generation education, research and outreach. A major economic engine, Health Sciences employs nearly 5,000 people, has approximately 4,000 students and 900 faculty members, and garners $200 million in research grants and contracts annually. For more information: uahs.arizona.edu (Follow us: Facebook | Twitter | YouTube | LinkedIn | Instagram).