Improving Health Equity for the Aging LGBTQ+ Community

For health care providers, increasing awareness and sensitivity to individual needs is key, say two Health Sciences aging experts.

As the population ages, so do members of the LGBTQ+ community. Health care providers must be ready to respond to their individual needs.

Healthy aging may be challenging for everyone, but for older LGBTQ+ people, health care challenges can be amplified. Members of the community have an increased lifetime risk for employment, housing and social discrimination, and are less likely to have children or receive Social Security or pension incomes when a partner dies. By the time they reach old age, these factors can put them at a profound disadvantage.

“Challenges based on ageism and aging stand by themselves. Layer on top of that the challenges that come from a history of stigma and discrimination that LGBTQ+ people have endured,” said Amanda Sokan, PhD, MHA, LLB, assistant professor in the department of public health practice and translational research at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health.

Amanda Sokan, PhD, MHA, LLB

“In old age, a lot of LGBTQ+ people go back in the closet, because they’re afraid of a repetition of that history of stigma and discrimination, they’re reluctant to come out to their health care providers, they’re hesitant to seek social services,” Dr. Sokan said.

Providing care that is sensitive to an individual’s overall experiences and health needs, especially those who are part of communities that traditionally have been underserved, is a key tenet of the University of Arizona Health Sciences’ approach to training health care professionals.

“Care providers have an obligation to heal others by taking an inclusive approach to serve the needs of the whole person,” said Michael D. Dake, MD, senior vice president for the University of Arizona Health Sciences. “Health care professionals must understand how one’s identity, experiences and relationships with the world might affect their health. Creating a care environment in which LGBTQ+ individuals and their families feel safe and included can lead to a more trusting relationship, improved communication and more effective treatment plans.”

Linda Phillips, PhD, RN

“If you have a patient and you assume he’s heterosexual, you’re going to ask questions based on that assumption,” Dr. Sokan said. “You might not ask him to take an HIV test, when one of the fastest-growing populations for HIV is older adults.”

“People who are trans have some really difficult issues,” added Linda Phillips, PhD, RN, professor of medicine and nursing and senior director of research/innovation for the Arizona Center on Aging. She referred to a recent report detailing the discrimination transgender people face in health care, including verbal abuse, refusal to acknowledge preferred pronouns and unfamiliarity with gender-affirming therapies. “Nursing home staff who don’t have a clue may not support clothing choices. There may be a great deal of embarrassment about undressing and dressing.”

Understanding the community

Dr. Sokan says many factors, including the stress of discrimination and stigma and poor access to culturally competent health care, contribute to health disparities affecting the LGBTQ+ population: higher rates of disability, drinking, smoking, chronic conditions, mental illness, loneliness and isolation. She was careful, though, to highlight the incredible diversity across this community.

“Even within the LGBTQ+ population, there are within-group variations,” Dr. Sokan said. “We cannot put every subgroup within that LGBTQ+ population into one box.”

Older LGBTQ+ populations are at risk for greater isolation as they age because they are less likely to have children and more likely to have lost family connections as well.

“This is not a homogeneous group,” Dr. Phillips said. “There is a slice of LGBTQ+ people who are incredibly privileged, with high incomes, good education, good jobs. They have less risk than other segments, who are plagued with the problems of low income and low education and the associated health risks. Those things have to be taken into consideration in providing services for the population.”

Dr. Phillips says an important part of health equity lies in recognizing differences.

“Often people think treating everyone the same is a part of equity. That’s a fallacy. People are not the same,” Dr. Phillips said. “I want my students to have an appreciation for the differences and learn to respond to those differences in a meaningful way.”

Countering social isolation

Older adults as a group are at higher risk for social isolation, but older LGBTQ+ adults face a further increased risk. They are less likely to have children, and more likely to have been rejected by their families of origin and religious institutions.

“For those who are aging now, they’ve come through the battle of fire. They are the generation who were kicked out by their families, who were shunned,” Dr. Sokan said. “They’re more likely to be isolated, not to have the social connections that some of us take for granted.”

“The patient-doctor relationship should be a partnership of communication, openness and trust.”Amanda Sokan, PhD, MHA, LLB

Dr. Phillips says this isolation can lead to older LGBTQ+ people falling through the cracks of the health care system. For example, while LGBTQ+ people aren’t at a higher risk for dementia, they are less likely to be diagnosed than other older people. Dr. Phillips, along with Rebecca Perry Tardiff, evaluator at the Arizona Center on Aging, has been working with the Pima Council on Aging to launch Dementia Capable Southern Arizona, a project funded by a grant from the Administration on Community Living. The group’s goal is to increase screening and services in harder-to-reach populations, including older LGBTQ+ people.

“Dementia is often unrecognized in this group,” Dr. Phillips said. “Often, older adults who are LGBTQ+ are living alone. And if you’re living alone, there’s a lot of hiding that goes on, because you don’t want people to haul you out of the household and put you somewhere.”

Dr. Phillips says some older LGBTQ+ people may go back into the closet when they enter assisted living facilities because of the stigma that surrounds their sexuality and gender identities.

“One of the advantages of residential living is socialization,” Dr. Phillips said. “If you don’t know what your reception is going to be, you isolate yourself. If you are socially isolating, it defeats the purpose.”

Struggling to find support services can compound social isolation. Dr. Phillips says health care providers need to start conversations about long-term care and advance directives, and help partners and loved ones understand the complicated bureaucracy they must navigate after a patient’s death. She cites a pressing need for support groups for caregivers and grief groups for surviving partners, who urgently need community when dealing with end-of-life issues.

“I recently had a close friend who died in a hospice. Her wife was with her, and they were well cared for within the hospice,” Dr. Phillips said. “The problems came after her death. There were no bereavement groups that my friend felt were appropriate, that responded to her needs. The fight with Social Security was unbelievable.”

Creating inclusive care

Dr. Sokan says it’s not enough to have good health care; it needs to be delivered by people who are committed to serving all patients, without judgment and in response to their unique needs.

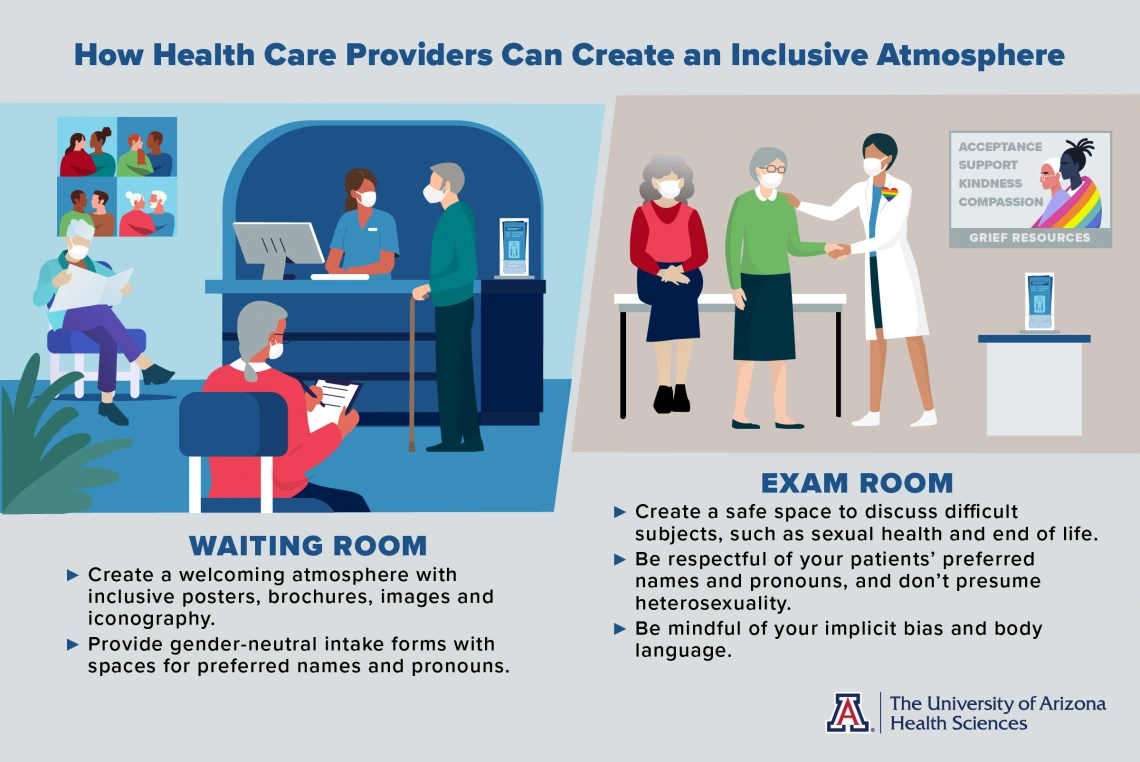

“Quality of health care might be absolutely awesome, but if it is not inclusive, that quality could be through the roof and have no direct impact for LGBTQ+ older adults. Ultimately, our goal has to be dignity, respect and care,” Dr. Sokan said. She added that providers can signal inclusivity by incorporating welcoming wording and imagery on their websites and in their facilities, and by being mindful of the assumptions they’re making when they ask questions about gender and relationships.

Both Drs. Sokan and Phillips have seen progress over the years.

“Very slowly, intake forms have changed,” Dr. Phillips said of the increased prevalence of gender-neutral forms that ask for the name of a spouse rather than a husband or wife, or forms with spaces for preferred names and pronouns. “I see same-sex couples on television, even in ads. I think there’s more general acceptance.”

They say older LGBTQ+ patients also can benefit from encounters with health care providers who create a safe space for open and transparent communication.

“It’s difficult, after a history of so much pain and discrimination, for a patient to step out of their comfort zone with a health care provider, but it’s important that providers are aware of a patient’s sexual orientation or gender identity, because it allows for appropriate conversations about sexual health and health risks,” Dr. Sokan said. “The patient-doctor relationship should be a partnership of communication, openness and trust, especially for LGBTQ+ older adults.”