The Power of Hormones in Treating Pain and Addiction in Women

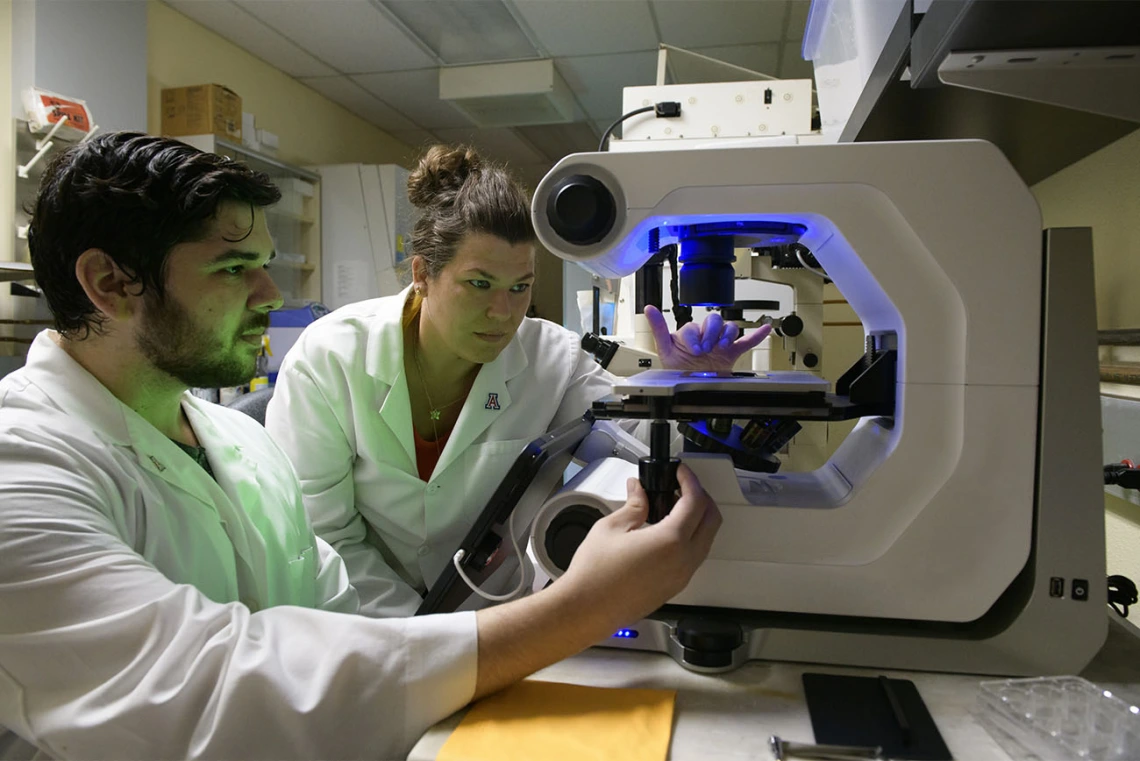

Researchers in the Comprehensive Center for Pain and Addiction study hormones to understand why women experience pain and addiction differently from men.

Researchers in the University of Arizona Health Sciences Comprehensive Pain and Addiction Center are working toward closing a 20- to 30-year gap in understanding the link between female hormones, pain and addiction.

Chronic pain and pain disorders such as migraine and fibromyalgia affect women at disproportionately higher rates than men. Migraine, for example, affects approximately 39 million Americans, the majority of whom – 28 million – are women, according to the Migraine Research Foundation. Despite this, women largely have been absent from clinical trials studying chronic pain conditions, which has hampered understanding and treatment options.

Tally Largent-Milnes, PhD, assistant professor of pharmacology at the College of Medicine – Tucson.

Two researchers in the University of Arizona Health Sciences Comprehensive Center for Pain and Addiction are working toward closing a 20- to 30-year gap in understanding the link between female hormones, pain and addiction, in an effort to improve the quality of women’s lives.

Hormones and headaches

Migraine can significantly impact a person’s life. Those affected by migraine may experience nausea, vomiting, dizziness and sensitivity to touch, sound, light and smell, as well as headaches. Seventy-two percent of women affected by migraine say headaches affect their ability to care for their families, and 68% say they hinder their productivity at work, according to the Lilly Migraine Impact Report.

“Their responsibilities at home and at work are suffering,” said Tally Largent-Milnes, PhD, an assistant professor of pharmacology in the UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson. “It’s not just migraine patients who are affected – it’s caregivers, friends and family. It's taking a much larger societal toll than just the migraine patient having a headache and being in pain.”

Dr. Largent-Milnes began her career studying pain as a general topic, and quickly centered her focus on women after finding a gap in research taking into account female biology.

Alicia M. Allen, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of family and community medicine at the College of Medicine – Tucson.

Data from female study participants were traditionally considered unreliable due to the normal hormone fluctuations that occur during menstrual cycles, Dr. Largent-Milnes said.

In 2017, Dr. Largent-Milnes began studying the impact of those hormone fluctuations on migraine headaches. One early study found that injecting high doses of estrogen could induce a headache. The idea led to a narrowing of her research focus on manipulating hormones to control pain.

She is currently examining the presence of estrogen in cortical spreading depression, which is the underlying mechanism of migraine aura, a temporary visual disturbance. She also is studying sex differences in the endocannabinoid system and their impact on migraine headaches.

“The goal is to grow the knowledge of the field,” Dr. Largent-Milnes said. “And the ultimate goal is to understand pain pathology enough that we can design drugs that are actually disease-modifying for women.”

Hormones and addiction

Complementing Dr. Largent-Milnes’ research on the relationship between pain and hormones, Alicia M. Allen, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of family and community medicine in the College of Medicine – Tucson, is studying the impact of hormones on addiction.

Dr. Allen’s early work examined how changing hormones impacted a woman’s desire to smoke. In recent years, her work has turned to investigating opioid addiction in women, homing in on pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Dr. Largent-Milnes began her career studying pain as a general topic, and quickly shifted her focus on women after finding a gap in research taking into account female biology.

She leads a study called Observing Relationships between Caregiving and Hormones after Infant Delivery (ORCHID), which seeks to answer the question: Could hormones help women avoid using opioids in the postpartum period?

“For women who misuse opioids, the postpartum period is an ideal time for intervention and making permanent change, but it’s also a time of very high risk,” Dr. Allen said. “While the mother is in a prime place to get treatment and maintain recovery, the flip side is that the postpartum period is when relapse rates are very high – about 80% of women relapse within the first year of childbirth.”

The ovarian hormones progesterone and estrogen impact the drug-reward response in the brain, primarily with nicotine and cocaine, Dr. Allen said. When progesterone and estrogen levels are high, dopamine is released at a higher rate than when hormone levels are low. This dramatic hormone shift could impact opioid use during the menstrual cycle and after childbirth.

“Understanding this hormone shift is particularly important in the postpartum period,” Dr. Allen said. “When a woman becomes pregnant, her hormones are really high. Then she has the baby, and the hormones dramatically drop off. In a day or two, they plummet.”

The postpartum hormone shift also could affect a woman’s mood and opioid cravings, and whether a treatment such as methadone would be successful.

In recent years, Dr. Allen’s work has turned to investigating opioid addiction in women, homing in on pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Pregnant women with or without opioid use disorder can participate in the ORCHID study, which tracks hormones, mood, substance use and social support for five months following childbirth. ORCHID researchers also compare different types of infant caregiving, such as skin-to-skin contact or carrying a baby close to the body in a wrap or device to prompt a hormonal response that could protect against relapse.

In the future, Dr. Allen hopes to expand her research to examine how women with substance use disorders can manage pain during pregnancy and delivery.

“I hear over and over again how challenging it can be for women who have a substance use disorder and are in the hospital having a baby to receive adequate treatment for pain,” Dr. Allen said. “There's concern from medical personnel about giving them pain medications. There’s some stigma, and because of that, it’s a big issue that needs to be sorted out.”

Contact

Margarita Bauzá

mbauza@arizona.edu