All the world’s a stage for prolific playwrighting professor

College of Medicine – Tucson’s Mel Hector finds inspiration all around him.

Mel Hector, MD, (in blue shirt wearing headphones), an associate clinical professor in the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson’s Department of Medicine, watches a reading of one of the plays he has written.

Photo by Noelle Haro-Gomez, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

Menopause changed Mel Hector, MD.

Well, to be more specific, it was “Menopause The Musical” that had a profound effect on him. When the associate clinical professor in the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson’s Department of Medicine saw the parody with his wife, Paige, it inspired him to write his own musical.

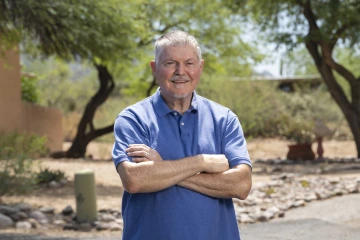

Mel Hector caught the writing bug after seeing “Menopause The Musical.”

Photo by Noelle Haro-Gomez, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

At the time, Hector, a specialist in geriatrics, was the medical director of a long-term care facility. His musical, called “St. Beseenya” and chock-full of parody songs, was set in a nursing home and touched on “all the issues that come along with long-term care – the sexuality, the diet, the treatment or not treatment, medical mistakes, death.”

That was Hector’s foray into playwriting. Now, fiftysomething plays and 10 years later, Hector humbly thinks of himself as a newbie.

“I’m still a beginner and happy to be,” said the soft-spoken father of six.

A natural progression

Though he did a two-year fellowship in geriatrics, Hector initially started off practicing family medicine. When Mindy J. Fain, MD, chief of the U of A College of Medicine – Tucson’s Division of General Internal Medicine, Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, reached out to Hector four years ago, he was working in the private sector. The invitation to return to teaching and his roots was “a dream.”

He taught family medicine at the University of Missouri and geriatrics at Johns Hopkins University before serving off and on as a preceptor for U of A geriatric fellows in the 1990s. Hector, who holds more than a dozen patents for medical inventions, is working on a research project with the U of A College of Engineering. The team is in the initial stages of testing radar units as an alternative to cameras for fall prevention and management in nursing homes.

The hope is that the inexpensive radar technology, which is small and unobtrusive, can not only detect but also predict falls, which are a big issue in facilities for the elderly.

“If you had asked me fresh out of medical school – when I was still doing obstetrics, doing a lot of deliveries, doing emergency room, going to the intensive care unit, going to the critical care unit and the operating room, as family medicine doctors do – I would have never seen myself doing geriatrics,” he said. “It was just not even on my radar.”

As he and his patients aged, though, geriatrics was a natural segue.

“It just evolved as I got older into taking care of my peer group more than anything else,” Hector said. “But I also think it was largely influenced by my grandparents raising me.”

A winding path

Hector was 5 when his parents got divorced. They sent him to live with his grandparents on their Missouri farm. After his grandmother died, his grandfather, a Baptist deacon and itinerant construction contractor, moved his grandson across the Midwest.

“By the time I finished high school, I had been to well over a dozen different schools,” Hector said. “Because we moved so much, I never made friends. I made libraries.”

While Hector loved to read, he never fancied himself a writer. After graduating from high school, he had seven full-ride college scholarship offers to study engineering and math. Neither interested him. He enlisted in the Marines and got sent to Vietnam, where he was wounded in three separate incidents. Hector described the injuries to his knee, ankle and back as mere nuisances that haven’t kept him from running marathons or jumping out of planes. Still, he said, “If you spend enough time in the hospital in Vietnam, they will not let you come back to Vietnam.”

Hector was sent back to the states to recuperate, and with the GI Bill at his disposal, he opted for college and medical school.

Write on

Hector is inspired by medicine and the patients he sees in telehealth visits. But he finds topics to tackle everywhere, including his own life and news headlines. The subject matter is typically pretty heavy, like chemical dependency, discrimination or death.

Mel Hector finds inspiration for his plays from news stories and life.

Photo by Noelle Haro-Gomez, U of A Health Sciences Office of Communications

Hector, who was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2021 and underwent a bone marrow transplant, is a longtime member of the Old Pueblo Playwrights, a nonprofit group that promotes the work of Tucson authors for stage or screen.

The group hosts weekly readings and an annual New Play Festival. This year, the festival included Hector’s “Anything That Doesn’t Kill You,” a piece that focuses on teen angst and obesity. He loves workshopping pieces that touch your heart and is less concerned about getting works up on stage than he is about polishing them so they’re as good as they can be.

“When I write a play, I can do fine with plot and structure and developments,” he said. “What I really have to work on is making believable, real characters who emote because I spent a lifetime not emoting.”

Hector, whose latest project is a collaboration on a children’s book about Halloween, figures he’s written enough plays to host his own festival, not that he ever would. As much as he enjoys playwrighting, his dream isn’t of Broadway or big-name actors playing his roles. He just wants to create something that touches people on a basic human level.

“To write a play and translate something, whether it’s PTSD or whatever the topic is, if it’s something that people can relate to and understand and not feel that I’m preaching and that when they walk out, they get it, they understand better,” Hector said. “I think if that could happen, if that ever happened, that would be more than enough.”