Should cannabis still be a Schedule I drug?

The Drug Enforcement Agency received a recommendation to reclassify cannabis as a Schedule III drug, a move that would be a boon to research and patient care.

Comprehensive Pain and Addiction Center researchers say reclassifying cannabis as a Schedule III substance would loosen the restraints on research into possible benefits, as well as any potential negative side effects, of medical marijuana.

It all starts with a license application. There are background checks to pass, not only for the person applying, but also for their colleagues and employees. Then, federal agents show up on site to confirm that a lockable safe is securely bolted to the concrete floor of a lockable room. When work begins, the safe can only be opened by someone on the Drug Enforcement Agency approved persons list. Everything about the contents must be dutifully recorded, including where it came from, when it was removed from the safe, how it was used, and when it was returned to the safe or disposed of.

Todd Vanderah, PhD, director of the Comprehensive Pain and Addiction Center at the University of Arizona Health Sciences, has spent two decades studying cannabinoids, including their potential as a treatment for metastatic cancer-related bone pain.

It might sound like a system used to safeguard priceless antiquities, but it isn’t. Instead, it is a fact of life for researchers who want to conduct experiments using cannabis. Nothing about studying cannabis is easy, but the reason for the high security is simple – cannabis is a Schedule I drug, alongside heroin, LSD and ecstasy.

“The federal government says that anything that comes from the medical marijuana plant is a Schedule I drug, which is any drug that has no medicinal purpose,” said Todd Vanderah, PhD, director of the University of Arizona Health Sciences Comprehensive Center for Pain and Addiction. “But there is not a lot of research to know what the benefits and harms are that come along with cannabis or medical marijuana.”

Vanderah has been researching cannabinoids – naturally occurring compounds found in the Cannabis sativa plant – for nearly 20 years and is currently a professor and head of the Department of Pharmacology at the UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson. He believes cannabis more correctly fits under Schedule III, alongside products containing less than 90 milligrams of codeine per dose – Tylenol with codeine, for example – ketamine, anabolic steroids and testosterone.

He is not alone. Cannabis’ Schedule I classification has been challenged several times, most recently by Rachel Levine, assistant secretary for health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, after President Joe Biden requested a scientific and medical review. The Health and Human Services’ recommendation, sent to DEA head Anne Milgram in late August, is to reclassify cannabis as a Schedule III drug.

Schedule I drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.

Cannabis policy, then and now

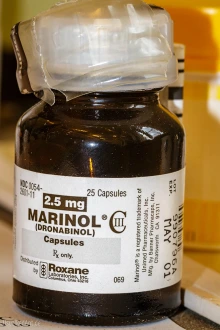

Dronabinol, marketed under the brand names Marinol or Syndros, is an FDA-approved synthetic form of THC used to treat nausea and vomiting caused by cancer chemotherapy, as well as loss of appetite and weight loss in people who have acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. (Credit: Steffen Geyer/CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED)

Cannabis and the United States government have a long history together. In 1860, when cannabis was legal in the U.S., the first federal commission to study cannabis was created due to concerns about potential negative side effects.

Over the next century, regulations around cannabis sales and use increased: federal drug policies were enacted; cannabis possession was deemed illegal by many states; the Marijuana Tax Act was imposed; and cannabis was included in the Federal Narcotics Control Act. None were as impactful, though, as the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. It categorized all substances regulated under federal law into one of five classifications based upon the drug’s medical use, potential for abuse, and safety or dependence liability. Cannabis was classified as a Schedule 1 drug, where it has remained ever since.

As time went on, researchers studying the two most well-known cannabinoids – THC and CBD – identified medical uses for both that led the Food and Drug Administration to approve four cannabis-derived or -related medications:

- Epidiolex, which contains CBD and is used to treat two rare and serious forms of epilepsy;

- Marinol and Syndros, which contain a synthetic form of THC called dronabinol and are used to treat loss of appetite and weight loss in AIDS patients; and,

- Cesamet, which contains a synthetic compound with a chemical structure similar to THC called nabilone and is used to treat nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy.

The dichotomy between the FDA’s approval of those drugs and the DEA’s Schedule I definition is clear – science has shown that some parts of the Cannabis sativa plant have medicinal value.

Opening the doors for research

Lowering cannabis to Schedule III would loosen the restraints on research into other possible benefits, as well as any potential negative side effects.

The Cannabis sativa plant researchers currently have access to has significantly lower percentages of THC than many of the products being sold in states where medical or recreational marijuana is legal. Vanderah believes higher levels of THC may be causing more extreme side effects, but he cannot test that hypothesis until cannabis is removed from the Schedule I list.

“If cannabis wasn’t a Schedule I drug, there would be more scientists doing research, which means more interest in this area and more research funding,” Vanderah said. “We would have many more unique cannabinoid compounds to use as tools to understand the different types of receptors and their functions. Right now, a lot of that is unknown – we are still stuck with THC and CBD.”

Research into opiates, by comparison, has flourished over the last 50 years. Scientists have uncovered the benefits, risks and negative effects of a variety of opioid compounds, ranging from loperamide, which does not cross the blood-brain barrier and is commonly used to treat diarrhea, to codeine and fentanyl. Recent research into kappa opioids has resulted in compounds that may be helpful for conditions such as depression, as well as medication-assisted treatments.

Hydrocodone, oxycodone, cocaine, methamphetamine and fentanyl are all classified as Schedule II drugs, making them easier to research than cannabis.

Schedule III drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with a moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence.

Additionally, scientists who hope to study cannabinoids cannot simply walk down to the nearest dispensary and buy some CBD or medical marijuana. Only cannabis from federally approved growers can be used in published research studies, even though the THC levels often fall far below what is being sold in dispensaries in states where marijuana is legal for recreational or medical use.

“The other reason there is not a lot of cannabis research is because there is still a stigma around the fact that you are studying something that is federally illegal and has a reputation as a gateway drug that is going to cause more addiction,” Vanderah said. “Making cannabis a Schedule III drug would open the doors to say, ‘Hey, this is relevant. We should have more people doing this.’ It would reduce the stigma that we’ve had for many, many years on doing research on cannabis.”

Giving doctors another tool to combat pain

One of the most challenging areas of research when it comes to Schedule I drugs is clinical trials. Vanderah believes a Schedule III classification for cannabis would make it much easier to transition basic science findings into human studies, which could be good news for pain management physicians including Mohab Ibrahim, MD, PhD, associate director of medical affairs for the Comprehensive Centerfor Pain and Addiction. Ibrahim sees patients at the Banner – University Medical Center Chronic Pain Management Clinic and is a professor of anesthesiology at the College of Medicine – Tucson.

Mohab Ibrahim, MD, PhD, associate director of medical affairs for the Comprehensive Pain and Addiction Center, is a pain management physician who did his doctoral research on cannabinoids. He says reclassifying cannabis as a Schedule III drug could reduce the hesitancy of some physicians to prescribe medical marijuana and make patients feel less stigmatized about its use.

“From a physician standpoint, recategorizing cannabis as a Schedule III drug would have huge implications,” Ibrahim said. “When something is Schedule I, meaning it has a very high potential for abuse and probably no medical benefit, many physicians are very hesitant to even consider it. The transition from Schedule I to Schedule III will encourage physicians who see benefits for medical marijuana to be able to prescribe it or at least recommend it.”

Ibrahim also believes a Schedule III classification for cannabis would make medical marijuana more acceptable from a societal standpoint, which should make patients feel less stigmatized and more willing to try it. Several studies have shown that when states legalize recreational or medical marijuana, the overall use of opioids for pain decreases.

Additionally, patients should find it easier to travel between states with a doctor’s prescription for a Schedule III drug. Currently, it is not legal to cross state lines with cannabis, even when traveling between two states that have similar marijuana laws.

“At the end of the day, it’s a medication, and just like any other medication, it can still be misused and mis-prescribed. But that applies to almost every medication in the market, from the most addictive opioid to the least harmful, benign antacid that you can get over the counter,” Ibrahim said. “The positive part is that physicians will have an additional tool to manage chronic conditions, and one that potentially has fewer side effects than many of the medications on the market right now. But just like any medication, physicians need to understand the indications and contraindications for medical marijuana.”

While recategorizing cannabis as a Schedule III drug would create tangible benefits for research and patient care, the Health and Human Services’ recommendation could face an uphill battle with the Drug Enforcement Agency. Since 1981, multiple proposals to remove cannabis from the Schedule I category have been introduced and failed, with the most recent in 2016. Still, in 1999 the DEA acted on the HHS’ advice when reclassifying Marinol as a Schedule III drug, and in 2017 it classified Syndros as a Schedule II substance.

“It all comes back to the plant. The plant itself is like a little compounding pharmacy. I believe that what we are seeing from the medical marijuana plant is a synergistic effect of several compounds,” Vanderah said, reiterating the need for more research and the Schedule III reclassification that could make it all possible. “What compounds can we remove that would make it less toxic or addictive, removing some of the unwanted side effects of cannabis? What are the five chemicals that, when combined, produce a very nice pain relief that's not only inhibiting pain but also decreasing inflammation, and maybe having an effect in the central nervous system so that a person is not worried, stressed or depressed about their pain? Those are the kinds of questions we need to answer with research.”

Our Experts

Todd Vanderah, PhD

Director, Comprehensive Center for Pain and Addiction

Regents Professor, Department of Pharmacology, College of Medicine – Tucson

Department Head, Department of Pharmacology, College of Medicine – Tucson

Co-Director, MD/PhD Dual Degree Program

Assistant Vice President, Research and Innovation, Global MD Program

Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, College of Medicine – Tucson

Professor, Department of Neurology, College of Medicine – Tucson

Member, BIO5 Institute

Member, Cancer Biology Program, UArizona Cancer Center

Mohab Ibrahim, MD, PhD

Associate Director of Medical Affairs, Comprehensive Center for Pain and Addiction

Director, Banner Health Chronic Pain Management Clinic

Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, College of Medicine – Tucson

Program Director, Pain Medicine Fellowship

Member, Clinical and Translational Oncology Program, UArizona Cancer Center

Contact

Stacy Pigott

UArizona Health Sciences Office of Communications

520-539-4152, spigott@arizona.edu