Finding better paths to treat pain and prevent addiction

Throughout his career spent studying opioids, Todd Vanderah, PhD, has been determined to find a way to manage pain without increasing the risk of addiction.

In December 1995, the Food and Drug Administration approved OxyContin to treat moderate to severe chronic pain. In Tucson, Arizona, a newly graduated postdoctoral research scientist at the University of Arizona Health Sciences listened to the news with dismay.

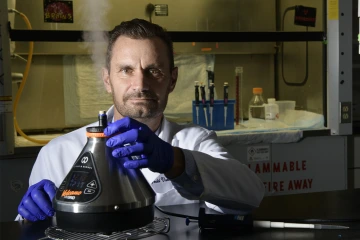

Todd Vanderah, PhD, is a professor and head of the College of Medicine – Tucson Department of Pharmacology and interim director of the UArizona Health Sciences Comprehensive Center for Pain and Addiction.

At the time, FDA experts believed the extended-release formulation of the powerful opiate oxycodone would have less abuse potential than other opiates because the drug would be absorbed slowly, without the resulting “high” that promotes addiction. But the young researcher had been studying opiates and non-opiate pain relievers since he was an undergraduate, and he didn’t buy into the FDA’s line of reasoning.

“During the early 1990s, we did all kinds of studies on new types of molecules that were not opiates and would not produce the respiratory depression or propensity towards addiction that opiates do,” said Todd Vanderah, PhD, interim director of the University of Arizona Health Sciences Comprehensive Center for Pain and Addiction. “I kept saying, ‘Opiates if overused or misused are dangerous. We have to come up with other ways to help those with chronic pain; this is not good.’ And it didn’t matter. There was a big wave when OxyContin came along – opiates were pushed forward and everything else we did was pushed away.”

It was years later before the FDA realized Vanderah and others like him were right. In the early 2000s, reports of overdoses and deaths from prescription drugs began to rise sharply, with OxyContin at the center of the problem. According to the FDA, the number of people who admitted to using OxyContin for nonmedical purposes increased dramatically from approximately 400,000 in 1999 to 2.8 million in 2003.

It was 2010 before Purdue stopped shipping the original OxyContin to pharmacies, only after the FDA approved a reformulated version designed to make the drug more difficult to misuse or abuse. But the damage was already done. More than 1 million people in the U.S. have died from drug overdoses since 1999, with opioid-related deaths accounting for more of the total than any other cause.

Dr. Vanderah’s passion for pain and addiction research prompted him to spearhead the development of the University of Arizona Health Sciences Comprehensive Center for Pain and Addiction (CCPA). There, he and fellow CPAC members search for non-opioid alternatives to treat chronic pain.

“My interest in pain research was that I wanted to understand opiates. I still do,” said Vanderah, professor and head of the Department of Pharmacology in the UArizona College of Medicine – Tucson and a member of the BIO5 Institute. “When I did my PhD work here at the University of Arizona Health Sciences, I worked with two amazing scientists – Dr. Henry Yamamura and Dr. Frank Porreca.”

Frank Porreca, PhD, professor of pharmacology and interim associate research director of the Comprehensive Center for Pain and Addiction, remembered Vanderah as a dedicated student researcher whose interest in opioids grew during his time in the lab.

“When Todd joined the laboratory, we were highly focused on understanding the role of endogenous opioid peptides and their receptors in brain circuits,” said Porreca, who is still pursuing that line of research in his lab in the College of Medicine – Tucson. “Todd became a key person in driving forward the understanding of how endogenous opioid peptides interacted with the delta opioid receptor, and this was largely the basis of his PhD thesis in my lab.”

“I'm so glad I was able to learn from them and enter the field of pain and addiction research,” Vanderah said of his two mentors. “There are a lot of people with great need.”

The vicious cycle of opioid tolerance

Tangled in the addictive web opioids weave is the idea of tolerance – the longer a person takes an opioid, the more opioid they need to feel the same effect.

Opioids trigger the brain’s reward center to release dopamine and endorphins that not only mute sensations of pain, but also boost feelings of pleasure and well-being. Most people who take opioids develop a tolerance and may feel the need to take larger doses of opioids to continue feeling good. Yet no one knows why tolerance occurs.

“My interest in pain research was that I wanted to understand opiates. I still do.”

Todd Vanderah, PhD

“We investigated opioid tolerance and found that when opioids are present, the brainstem can turn on the pathways that promote pain,” Vanderah said, citing the finding as one of the most significant that has come out of his laboratory.

Pain, he explains, is an important survival mechanism, as the sensation of pain is what allows people to protect themselves from further harm and even death. Without pain, we wouldn’t survive.

“I believe that physiologically, if you shut off the sensation of pain for too long, your body tries to figure out how to overcome that,” Vanderah said of his continuing preclinical research into opioid tolerance. “Our finding suggests that opioid tolerance is the body trying to make pain to overcome the opioid.”

Vanderah’s desire to understand opioids led to him becoming one of the top pain and addiction researchers in the field. But it was a much more personal experience that resulted in his focus on cannabinoids and their potential usefulness for a specific type of cancer pain.

Finding a better way

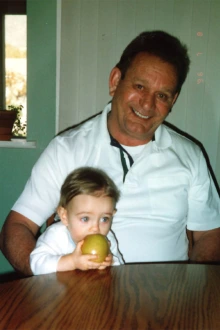

Vanderah’s father was only 58 years old when he died of lung cancer. The first sign anything was wrong came as father and son worked together on a house they were remodeling. The elder Vanderah complained of back pain, and when he went to the doctor the diagnosis was grim: stage 3 lung cancer that had metastasized to the bone.

Dr. Vanderah’s father, James Vanderah, had significant pain from metastatic lung cancer and dealt with negative side effects from opioids, which did little to manage the pain. The experience convinced Dr. Vanderah that opioids are not the best option for treating cancer pain.

Despite everything he knew about pain, Vandeah was powerless to take away the unbearable pain that coursed through his father’s body. His frustration grew in tandem with the ever-increasing amount of opioids his father took to find relief.

“The doses of opiates were huge,” Vanderah said, remembering the negative side effects his father experienced. “He was an absolute zombie, and the constipation was bad. It was a time where he couldn't enjoy the last parts of his life. It made me realize that opiates don't really do a lot of pain inhibition, they do more pain masking. They take your brain offline so that you don't think about the pain as much.”

Eventually, Vanderah’s father succumbed to the deadliest of opioid side effects: respiratory depression. As many cancer patients do, he took a high dose of opioids before bedtime to get some sleep. He never woke up.

Ten years later, Vanderah was golfing with Yamamura when the retired professor complained of back pain. He, too, was diagnosed with lung cancer. Losing both his father and a mentor who served as a father-figure to cancer convinced Vanderah he needed to devote part of his research to understanding cancer pain.

Why, he wondered, doesn’t lung cancer cause pain in the lungs before it metastasizes? Pain is the primary reason people go to doctors, so if the early stages of cancer were accompanied by pain, doctors might stand a better chance of treating it.

“A large contribution to the field of cancer pain, and what I hope to continue to advance, is research around the idea that when cancer metastasizes, it produces something in that environment to promote pain,” said Vanderah, who is focusing on the role of growth factors in cancer tumor growth, bone loss and metastatic cancer pain.

Dr. Vanderah has spent 20 years studying cannabinoids, including recently as a potential non-opioid solution for cancer pain.

He also believes there must be a better option than opioids for treating cancer pain. That line of inquiry led him to cannabinoids, the compounds found in the Cannabis sativa plant. While looking for alternatives to opioids, he stumbled across a paper where researchers in Israel found that cannabinoids could be beneficial for osteoporosis.

“I remember thinking, ‘This is it!’” he said. “I realized that the cells of the bone actually have CB2 receptors, one of the cannabinoid receptors. That’s all it took for me to decide I was going to look at cannabinoids for metastatic cancer pain.”

At the same time, Vanderah’s research is uncovering new information about how opioids affect metastatic cancer at the cellular level. In recent years, his preclinical research projects have led him to believe that chronic opioid use increases pain and enhances bone loss in metastatic cancer models.

Early results from his research on using unique, structured cannabinoids to inhibit pain are promising. Several papers are awaiting publication, including one based on a clinical trial he worked on with Pavani Chalasani, MD, MPH, associate professor in the College of Medicine – Tucson and member of the UArizona Cancer Center, to study the effects of an FDA-approved cannabinoid on pain and bone loss in cancer patients.

“The grand goal is to help patients with metastatic cancer with their pain and reduce the bone loss, possibly even decrease the proliferation of the tumor,” Vanderah said. “I feel like I’ve made progress in our ability to start treating metastatic cancer pain with something other than just opiates.”

Our Experts

Contact

Stacy Pigott

520-621-7239

spigott@arizona.edu