Confronting Vaccine Hesitancy with Facts and Empathy

Experts from the College of Medicine – Tucson are working to counteract fears surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine.

Getting the COVID-19 vaccine is the best way to protect yourself and society from infection with the novel coronavirus. Photo by Heather Hazzan, used under creative commons license from Self Magazine.

As COVID-19 vaccines roll out nationwide, health experts say stopping the pandemic may require 70 to 90% of the population to achieve immunity through infection or vaccination, leaving room for worry over the approximately 30% of people taking a wait-and-see approach to getting vaccinated. University of Arizona Health Sciences researchers at the College of Medicine – Tucson are connecting with “vaccine hesitant” individuals, encouraging them to reexamine their doubts.

Michael D.L. Johnson, PhD

A Pew Research survey found that more than half of Black respondents would “definitely” or “probably” avoid the vaccine. In response to vaccine hesitancy in this community, Dr. Johnson jumped at the opportunity for community outreach, speaking to Black churches and other organizations.

“One of my soapboxes has always been vaccines,” Dr. Johnson said. “More people are getting COVID in minority communities than others, and, in many respects prior to the development of this vaccine, our groups had been marginalized in research for quite some time. They want to know the vaccine is going to be something that’s for them, not against them. It’s helpful to have somebody who looks like you give you information about the vaccines, and it makes things more believable.”

Accelerated development

Dr. Johnson says one of the biggest concerns he has encountered is the idea that the COVID-19 vaccine was developed too quickly.

“We’ve moved at lightning speed to make this vaccine, which has been amazing,” Dr. Johnson said. “But you’re going to have people saying, ‘I don’t know about these vaccines. It was too fast.’”

Dr. Johnson assures audiences that, despite the condensed timeline, safety wasn’t neglected.

“In making the vaccine, a lot of time is spent assessing whether it will be financially feasible for the pharmaceutical company,” Dr. Johnson said. “That risk was mitigated by the government, which said, ‘We will front you the money and agree to buy the vaccines.’ The time they spent doing safety studies did not change, and went simultaneously with the manufacturing.”

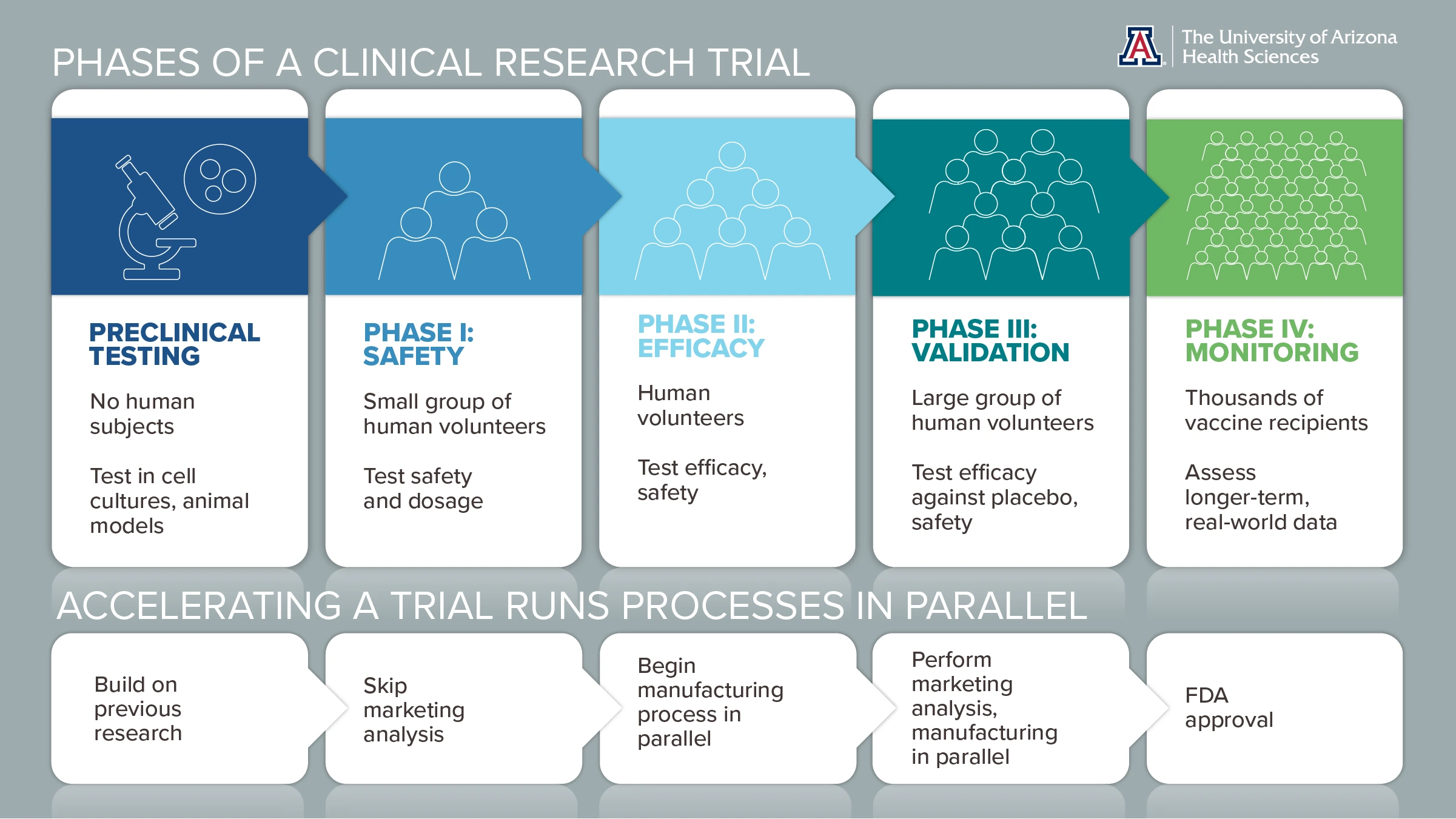

Click infographic to open full-size, printable PDF in a new window.

Click infographic to open full-size, printable PDF in a new window.

A vaccine gets its start in petri dishes and animal models to check for unexpected effects. Then, in clinical trials, it is tested in progressively larger groups of volunteers to monitor for safety and generate robust data.

“This vaccine has gone through a rigorous vetting process — it didn’t get here willy-nilly,” said Sairam Parthasarathy, MD, chief of the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, and principal investigator for Arizona’s CEAL group, which educates underserved communities about COVID-19.

A ready template

“This vaccine has gone through a rigorous vetting process — it didn’t get here willy-nilly.”Sairam Parthasarathy, MD, chief of the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine

Another factor in the vaccine’s rapid development was the ability to build upon a solid foundation of prior research, starting when the 2003 SARS epidemic triggered a flurry of coronavirus studies. Other discoveries paved the way for mRNA vaccines, which deliver genetic “blueprints” cells use to manufacture viral subunits — not the entire virus, but one tiny part that stimulates an immune response and memory.

“We have a lot of information on how coronaviruses and mRNA vaccines work,” Dr. Johnson said. “We had the template. We didn’t have to reinvent anything.”

He compares the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines to using a mix to bake a cake rather than making it from scratch.

“We moved this fast because we had a box of a lot of the ingredients. All we had to do was add eggs and oil and put it in the oven, and we got a great cake that tastes delicious,” Dr. Johnson said. “It’s a Duncan Hines vaccine.”

Fighting fear with facts

Another concern surfacing during Dr. Johnson’s outreach is apprehension over whether the vaccine was tested only in white volunteers. Francisco Moreno, MD, professor of psychiatry and associate vice president for the Health Sciences Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, has noted similar concerns among Hispanics.

Francisco Moreno, MD (center)

“People talk about how this hasn’t been tested in the Hispanic community. In fact, there was nice representation of Hispanics in the vaccine trials,” Dr. Moreno said. “The proportion of Hispanics who participated is greater than the proportion of Hispanics in our country, so we were more than included.”

“The vaccine was made with you in mind. African Americans and Latinx were included in the Moderna and Pfizer trials, and it had equal efficacy across the board for all groups,” Dr. Johnson said. “It was really important to feel like there were people at the table who looked like them.”

Another misconception is the vaccine could cause COVID-19 infection, but mRNA vaccines preclude that possibility by relying on viral subunits rather than whole particles.

“There’s no way the subunit can become the virus — zero chance whatsoever,” Dr. Parthasarathy said. “It’s like saying if I put a tire in your backyard and put an engine block next to it, it’s going to self-assemble into a car.”

Dr. Moreno says some people experience side effects that mimic mild illness, but that’s to be expected.

“Your body gets the immunological response,” he said. “That’s how we make an immunological memory to fight this virus.”

Sairam Parthasarathy, MD (left)

Dr. Parthasarathy says misunderstandings like these demonstrate the importance of widespread health literacy.

“We need basic education that puts people on a good path in life and preserves their health and humanity,” said Dr. Parthasarathy, who is also a member of the BIO5 Institute.

Health literacy goes hand in hand with trust in science. About 2 in 5 respondents to the Pew survey reported trusting scientists “a great deal” — numbers that leave room for improvement. Dr. Johnson says scientists must strive for accessibility.

“People in health-related fields have been thrust into the unexpected role of being scientific communicators. Not all of us are scientific communicators, and we need to be,” said Dr. Johnson, also a BIO5 member. “Putting yourself in uncomfortable situations to reach communities that aren’t in your bubble is an opportunity to break out of your echo chamber and have more personalized engagement. It’s harder to talk to people and find out what their concerns are, but it’s important.”