A Lasting Legacy: ‘Take Care of the Children’

A Phoenix mother speaks of a legacy of love, betting on talent and the University of Arizona Health Sciences’ promise of a healthier tomorrow.

Daniel Cracchiolo’s philanthropic gifts to the Steele Children’s Research Center aligned with his strong belief in helping children. His daughter, Marianne Cracchiolo Mago, is carrying on that tradition as the next generation of Steele Foundation leaders.

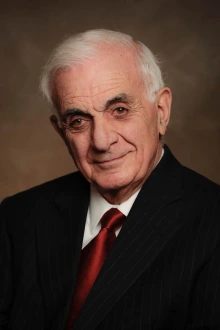

Lawyer and philanthropist Daniel Cracchiolo founded the Steele Foundation, which in 1990 made a $2 million naming gift to the Steele Children’s Research Center.

The phrase was a kind of unofficial mantra for Mago’s father, Daniel Cracchiolo: an injunction to care but also a reminder of what it takes to make a difference. Cracchiolo was an esteemed lawyer — a masterful litigator and courtroom crackerjack when necessary. But to those in the know, he was really a dealmaker at heart. He believed if people just put their heads together, with enough will, empathy and grit, they could accomplish most anything. But first, you have to give a damn.

The most profound expression of that credo may have been when Cracchiolo convinced Horace and Ethel Steele, longtime friends and clients, to establish the Steele Foundation, then took on leadership of the nascent philanthropy himself at the prime of his legal career.

Today, the words serve as an everyday reminder for Mago, who became president and CEO of the foundation in 2007. She experienced first-hand the impact of the Steele Foundation’s work when her own daughter was struggling with health issues that puzzled doctors at every turn.

“A thoughtful, patient-centered approach”

At age 14, Mago’s daughter Ginger repeatedly found herself gasping for breath. A competitive swimmer, she often was stopped dead by uncontrollable coughing fits during practice and meets. She began to tire easily, and her blood oxygen level would routinely test much too low for a seemingly otherwise healthy teen.

Marianne Cracchiolo Mago and her daughter Ginger embarked on a search for answers when Ginger began having trouble breathing during swim practice. Today, thanks to doctors at the Steele Children’s Research Center, Ginger is able to compete in swim meets again.

A swim coach guessed Ginger had exercise-induced asthma, but diagnostics didn’t bear that out. From one specialist to the next, Mago and her daughter made their way through a parade of breathing treatments and asthma medications. None really helped. Doctors considered the possibility of food allergies or an issue with her vocal cords. Tests and imaging said otherwise. A last-ditch prescription for steroids to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease failed.

After nine months of running in circles and ending up no closer to a diagnosis, let alone a solution, Mago took her daughter to the University of Arizona Steele Children’s Research Center in Tucson, the very facilities constructed with a $2 million gift from The Steele Foundation in 1990. The Steele Chidren’s Research Center is the research arm of the UArizona College of Medicine Tucson’s Department of Pediatrics.

In one visit, Ginger was seen by three of the center's top physicians: director and gastroenterologist Fayez K. Ghishan, MD; pulmonary specialist Cori Daines, MD; and allergist and immunologist Michael Daines, MD.

"It was just such a thoughtful, patient-centered approach — the classic Steele Center experience," Mago said, gratitude and relief still clear in her voice two years later.

Not long after, at Diamond Children’s Medical Center, doctors performed both a bronchoscopy and endoscopy, including tissue sampling. And after nearly a year of fruitless other pursuits, Ginger’s medical problems immediately became clear.

Betting on talent

Last fall, in its single largest investment to date, The Steele Foundation gave the University of Arizona $10 million to create the Daniel Cracchiolo Institute for Pediatric Autoimmune Disease Research at the Steele Children’s Research Center. Of the gift, $2 million is designated for the recently created UArizona Health Sciences Center for Advanced Molecular and Immunological Therapies, or CAMI, in what was the first private philanthropic support for the initiative.

Drs. Michael and Cori Daines were part of the Steele Children’s Research Center team that cared for Ginger Mago.

CAMI’s focus on autoimmune diseases and immunological therapies was a perfect fit for the Steele Foundation and the gift, Mago says, recounting early-days discussions with Dr. Ghishan and CAMI leadership about their research visions and missions.

“We don’t ever want to prescribe direction,” Mago says of the Steele Foundation’s approach to giving. “We’re not the experts, but this was a case where it was clear that our goals were in sync from the start.”

Research on immunotherapies, the immune response and autoimmune disorders are the very frontier of medicine today, the 2020s equivalent to genetics research and the culmination of the Human Genome Project in the early 2000s. Many experts now posit a “six degrees of separation” for all diseases, and new research is revealing every day just how many illnesses tie back to the immune response in some way.

The proposition also appealed to Mago's own well-honed business instincts. Before leading the Steele Foundation, she’d built a successful career as a senior executive in television. She started as an assistant to comedian Jon Stewart but was always “gravitating to the writing room.” Ultimately, that interest led her into a career in TV development, where she was part of the team that launched The Sopranos, Big Bang Theory and other shows that became defining programming of the 20th century.

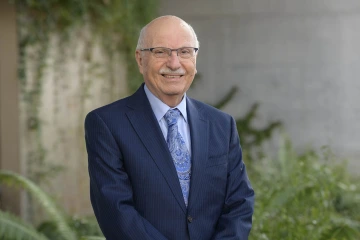

Fayez K. Ghishan, MD, director of the Steele Children’s Research Center, was a trusted friend of Cracchiolo and remains friends with Mago and her family today.

“My career was betting on talent,” Mago said.

From stacks and stacks of scripts, her challenge was to zero in on the one or two that didn’t just showcase skill and talent, but also that ineffable something that elevated them above all the rest. It was great preparation for leading a philanthropy seeking out the handful of opportunities that will produce the greatest long-range results.

To that end, Mago is excited about not just the medical but also the economic potential from work that stems from CAMI and the Daniel Cracchiolo Institute for Pediatric Autoimmune Disease Research. What other businesses will their research support? What startups could the foundation’s support ultimately help incubate? What innovations might be catalyzed, with researchers emboldened to take chances and explore ideas in ways they couldn't without this funding?

“Take care of the children”

Today, Mago’s daughter Ginger is thriving. It turned out she did have some asthma, but also anatomical anomalies that caused intermittent reflux — conditions that together presented an enigmatic constellation of symptoms outside the range of everyday medicine. Empowered with that information and embracing some lifestyle changes and a heightened interest in her own health and wellness, Ginger is managing her condition and back in the pool.

Her grandfather would be proud. Throughout his whole life, to his last years on Earth, Cracchiolo was deeply committed to the success, safety and well-being of children, Mago said.

Mago spoke at a University of Arizona Foundation luncheon in November 2022, when the Steele Foundation’s $10 million gift to the university was announced.

Her larger-than-life father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease at age 90 and grew increasingly quieter as a nonagenarian. But even at 93, when Mago and her brother asked him for advice one afternoon while having lunch at one of his favorite restaurants, Cracchiolo was clear in his conviction: “Take care of the children,” he said. Then again: “Take care of the children.”

“He lived that,” Mago said. “And what we’ve tried to do with this gift is honor that – honor my dad – and elevate his work and our work with kids, and to do that by supporting what was already a central focus of Steele Children’s, not some side project that would distract people from their most important work.”

Mago also suspects that if her dad were alive, he’d be abashed about the new center bearing his name.

“He was humble,” she said, describing her father as the son of immigrants, a first-generation college graduate, and a man who revered doctors in general and Dr. Ghishan in particular.

He had refused to put his name on the Steele Foundation, despite being its founder. But when Cracchiolo was persuading Mago to succeed him at the Steele Foundation, he told her that when she felt what it meant to be in a position to impact her community in such a positive way, to be part of that work, that she would understand herself how the opportunity had so enriched his life.

“I think he would be very, very embarrassed,” she said, “but also tickled pink, and quietly just so touched.”

Our Experts

Contact

Stacy Pigott

Health Sciences Office of Communications

520-539-4152

spigott@arizona.edu